In 1893, two young English ladies decided to establish a tea room in the Eternal City: Isabel Cargill, daughter of Captain Cargill, founder of the city of Dunedin in New Zealand and Anna Maria Babington, descendant of Antony Babington who had been hanged, drawn and quartered in 1589 for the part he had played in a conspiracy against Queen Elizabeth I. three years earlier.

Isabel Cargill and Anna Maria Babington invested their savings—£100 from Isabel and a more substantial sum by Ms Babington—in a tea and reading room for the English speaking community in Rome. For many years, young Englishmen had traditionally set off on the so-called ‘Grand Tour’, travelling round Europe in search of history, art and cultural exchanges. Around Rome’s Piazza di Spagna, the English had created a cultural enclave: Walter Scott lodged in Via delle Mercede 11, Turner in Piazza Mignanelli, Browning in Via Bocca di Leone and Lord Byron, close by, above the Spanish Steps where the Keats-Shelly museum is housed today.

The 5th of December 1893 saw the opening of the Tea Rooms in Via Due Macelli 66, only a short walking distance from Piazza di Spagna. They called it ‘Babingtons Tea Rooms’ because, between the two surnames, Babingtons was easier for Italians to pronounce. When opening their tea rooms in Via due Macelli, Anna Maria and Isabel had had to import all their equipment from England, above all, teapots, almost unknown in Italy, and china cups and saucers.

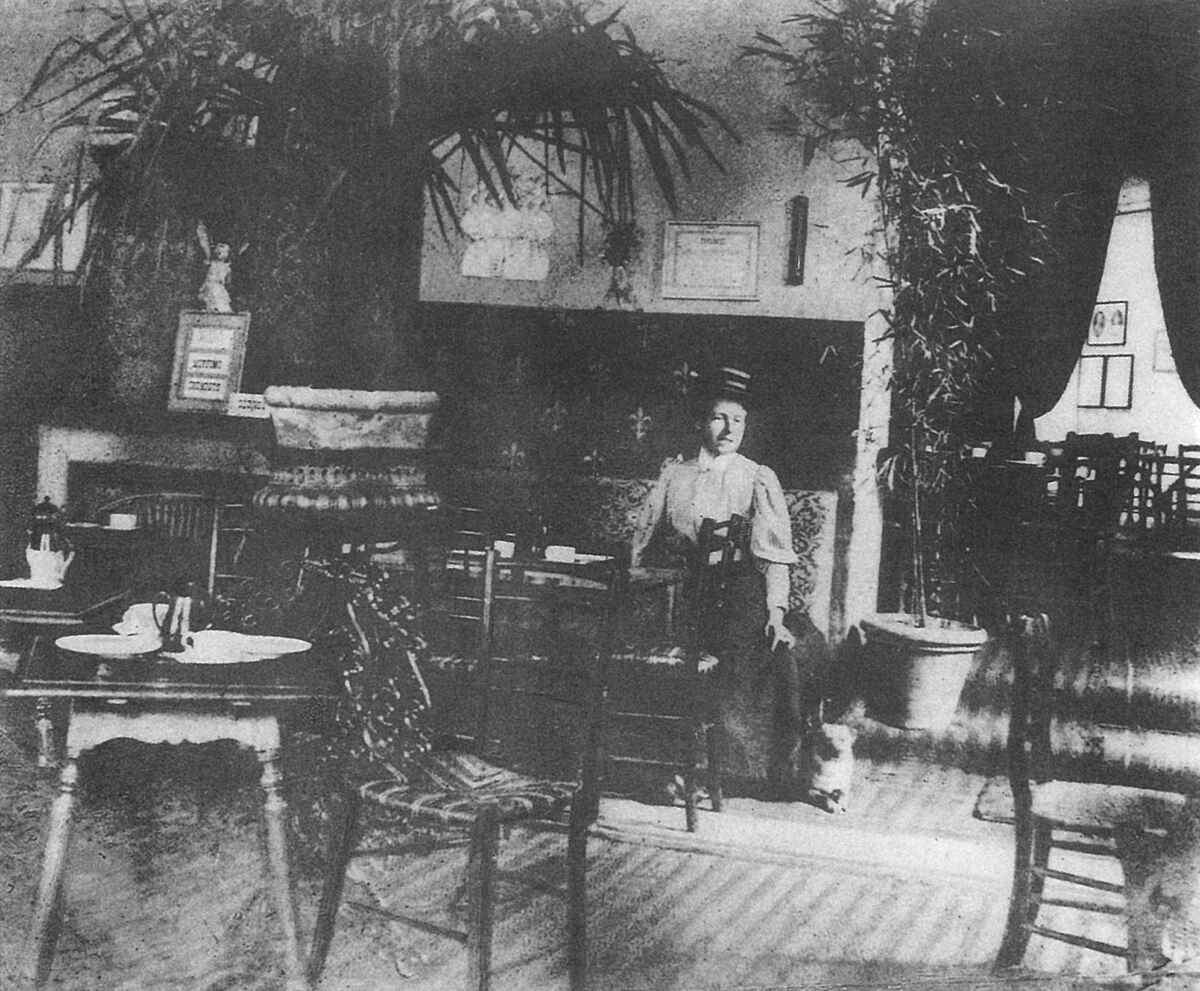

Lady in apron. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna 23-25, Roma, Italy.

Teapots at Amazon UK Teapots at Amazon US

White teas at Amazon UK

White Teas at Amazon US

At that time, in Rome, tea was only to be found in pharmacies and was sold solely for its medicinal properties. Tea was only known to the Italians as a remedy for fevers and digestive disorders. Its first appearance on the Italian scene went back to the sixteenth century, the era of busy trade between the Orient and the ports of Naples and Venice. In fact it is in Venice that we find the first mention of tea in the Western world, in a 16th century document written by Giovanni Battista Ramusio. This Venetian magistrate, a statesman, historian and linguist, slaked the intense thirst for news of the Orient, translating into Italian various stories of journeys made to Asia by European travellers in his three volume work On Navigations and Journeys (1550-1559). However, at the time of the opening of the Tea Rooms in Rome, tea continued to be known only for its medicinal properties. Not until the end of the eighteenth century had it started making rare appearances in the exclusive drawing rooms of the refined upper classes.

Even before the first cup of tea was served at Babingtons Tea Rooms, an English-language weekly published in the city—The Roman Herald—had already announced the upcoming novelty of a tea room in the Eternal City: ‘A long-felt want in Rome has at last been supplied, and that is, a Tea Rooms where ladies or gentlemen, hard at work sightseeing… could go to refresh themselves with a comforting cup of tea or coffee with the necessary adjuncts…’ A place where the atmosphere of England was recreated and where, in peace and quiet, books and newspapers could be read. ‘We feel sure,’ the article continued, ‘ that many of our readers will jump at the good news, as it will prove a great convenience as a meeting place now that the distances in Rome have so much increased’. The Roman Herald added that, with a monthly subscription of two francs, it was possible to use the reading room between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. Those who simply came to take tea could also use the reading room for a modest extra cost of ten cents. At the foot of the article the journal announced a great novelty: a small cabinet de toilette!

A few weeks later, just before Christmas, the two women put an advertisement in the same paper announcing that as well as tea, coffee was also served in the Tea Rooms. The first English Tea Room in the Italian capital was an almost instant success. Within a few months Anna Maria and Isabel found themselves with the Babingtons Tea Rooms full of customers every day.

The opening had become a major event for the city. Publications that went the rounds of the various societies did not fail to mention it, to write reviews and to make appointments to meet where, from morning until late afternoon, it was possible to find a good cup of tea. Properly made tea, that reminded one of home and family and one’s own land. One of these publications, evidently meticulously researched, informed the public under the title ‘An English Initiative’ that between December and March the two young women had served 3,175 cups of tea.

A present-day afternoon tea at Babingtons. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna, Rome.

The success was such that, within one year, in addition to the Via Due Macelli 66 tea room, the two young women decided to open another one near Saint Peter’s, in a little square that, with the building of the Via della Conciliazione, was eventually swallowed up in the main square in front of the Basilica. A flyer destined for the English community, dated 8th of June 1894, announces that visitors to St Peter’s could now find a good cup of tea a stone’s throw from the Basilica. It also specifies that females could make use of another ‘neat’ cabinet de toilette.

In 1896, Babingtons Tea Rooms moved to their current, more prestigious location at the foot of the Spanish Steps at Piazza di Spagna 23. Isabel Cargill and Anna Maria Babington not only served tea as well as cakes and pastries made on the premises. The cultural background the young women brought with them made them take part in the intellectual life of their co-nationals residing in Rome. The tables at Babingtons Tea Rooms became centres for lively debate. The old mixed with the young and intellectual debate and discussion became the life and soul of Babingtons while tea continued to flow in rivers.

The two ladies renovated Babingtons Palazzo—the Tea Rooms occupied a premises that had originally been the stables of the eighteenth century palazzo—and decorated it according to the late 19th century taste. Most of the furnishings were imported from England. The Roman Herald commented that Babingtons Tea Room became the meeting point where ‘the ladies and gentlemen, tired after the visit or occupied for personal reasons in the city center could, in a welcoming and pleasant environment, refresh themselves with a consoling cup of tea …’

In 1902 Isabel married the painter Giuseppe da Pozzo. She was thirty eight years old, he fifty five and from their marriage, in 1904, a daughter, Dorothy, was born, who would take over the running of the Tea Rooms when the time came for Isabel to retire. Dorothy described the interior of Babingtons Tea Rooms as follows: ‘Wall to wall coconut matting was laid on the floor and gas chandeliers installed. The walls were covered in dark green and brown embossed wall paper. It was furnished with square pitchpine tables for four with larger round tables in the corners. Upholstered seats lined the walls, a big ornamental palm stood in the middle of the first room and two plants of bamboo flanked the steps leading under the arch to the second room. Heavy dark red rep curtains were elegantly draped across this arch and gathered into two rings at the sides. The chairs were simple turned wood with green and straw-coloured straw seats. The tea-pots, made in Britannia metal, had been imported from England, as this comodity was unheard of in Italy…’

Surprisingly, the First World War did not have negative consequences for Babingtons where clients continued to enjoy their afternoon tea. To help out, Anna Maria and Isabel now gained the support of Anita De Santis and Giulia Nardone who during the next fifty years would become the backbone of the Tea Rooms.

However, in 1918 the Spanish flu started to spread, a pandemic which in two years killed tens of millions of people across the world, more victims than the war itself had caused. The flu was called ‘Spanish’ because the first rumours of it were only recorded in the Spanish newspapers. Spain had not taken part in the war and its press was therefore not subjected to censorship. In other countries, on the other hand, the violent outbreak of the virus was kept hidden. In reality, the virus was brought to Europe by the American Expeditionary Forces which had arrived in France in 1917 to take part in the Great War.

The flu arrived in Italy too. Giuseppe da Pozzo fell victim to the pandemic. His ailing heart gave out under the onslaught of pneumonia. It was 1919 and daughter Dorothy was only fifteen years old. A chain of events lead to the slowing down of the daily functioning of the Tea Rooms and a worrying period of decline began. War had changed life in Rome. Many foreigners had returned home on the outbreak of war. Romans changed their habits. Miss Babington, affectionately known as ‘Nonnina’ (little granny), was beginning to find a full day’s work too much for her. Isabel then became involved in the marriage of Dorothy to Count Attilio Bedini Jacobini and the birth in 1925 of a first grandchild, Giampaolo. The Tea Rooms suffered as a consequence.

The Wall Street crash in 1929 worsened the situation. In that same year, Anna Maria Babington died unexpectedly of a heart attack in Switzerland. Isabel found herself alone at a moment when the Tea Rooms was struggling with a multitude of problems.

The current owners of Babingtons: Rory Bruce and Chiara Bedini, the great-granddaughter of Isabel Cargill. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna, Rome.

In this moment of great difficulty, Isabel’s sister Annie took the decision to return to Rome to offer her support. So Isabel now found herself with her sister, her daughter Dorothy and the two head-waitresses Anita and Giulia to back her up, while in the kitchen, Crescenza held sway. Generous-spirited Annie, seeing her sister fatigued and saddened by the loss of Miss Babington, took the reins into her hands.

In addition, Annie decided to open an enterprise of her own. She rented an apartment, organised restructuring works and employed a squad of porters and waiters. Thus the Pensione Cargill came into being. She could have made a success of it were it not for the fact that, unlike her sister Isabel, she had no head for business. Staff and suppliers alike, recognising her weakness, helped themselves to provisions unhindered. Guests who pleaded poverty, truly or falsely, were allowed to stay on free of charge or leave without paying. Failure was inevitable, and she decided to give herself over to working full time at Babingtons, where she took over the chair behind the cash desk. Annie’s legacy, however, lives on in the present-day hotel called Hotel Londra e Cargill in Piazza Sallustio.

The Tea Rooms needed a radical make-over, restructuring, new equipment, a wider menu. Annie had the last of her small savings sent from New Zealand and invested them in Babingtons. She managed to involve the whole family. Dorothy’s husband Attilio called in his friend the architect Tullio Rossi to help with the interior design while the women occupied themselves with the upholstery, the curtains and the cushions. Parquet flooring was installed and the wall paper was replaced by dark wood pannelling with white paint above. Wall brackets took the place of hanging lamps. The tables were provided with straw mats with green or red borders, giving a touch of color. New china was ordered from the prestigious ceramics factory Richard Ginori. Its distinctive green was an eccentric choice at that period but has remained one of the defining features of the Tea Rooms. When the doors re-opened to the public, the success was immediate, with Annie at the cash desk, Isabel and Dorothy supervising the kitchen and Giulia and Anita keeping a stern eye on the bevy of newly-employed young waitresses.

During the twenty years of Fascist rule, one by one the various tea rooms in the city closed down. Their signs were removed and mention of them in guide books disappeared. ‘Foreign’ drinks like tea were not allowed to be served. Naturally Babingtons, occupying such a central position in the city, feared it would meet the same fate. But despite its English name, nothing ever happened to Babingtons. The English Tea Rooms stayed opened and welcomed different groups of political sympathisers. In the front room, members of the Fascist hierarchy met with their pro-regime allies while in the third room, just round the corner, the regime’s adversaries gathered. With the connivance of the staff, the anti-Fascists came and went via the kitchens, through a side door that gave directly onto the Piazza. The only other ‘danger’ was Aunt Annie, a decided opposer of the regime who could not keep her beliefs to herself. She held forth over Mussolini’s misdeeds and more than once loudly denounced his anti-democratic ways. Destiny stepped in, removing Annie from danger by taking her life.

In March 1939 another death struck at the heart of Babingtons: Count Attilio Bedini, Dorothy’s husband, was killed in a car crash in which his wife lost the movement in one eye. And while this tragedy was still fresh in the minds of all concerned, war broke out. For Dorothy it became increasingly difficult to carry on. As well as running the Tea Rooms she was responsible for her elderly ‘English’ mother Isabel and the upbringing of four children—Giampaolo, Leonardo, Valerio and Diana—in a city where danger was always lurking and food was becoming scarce. She was forced to take a decision: to leave Rome and take her children to a place of safety. They packed up their belongings and took refuge in Cortina d’Ampezzo, in those days a remote mountain village in the Dolomites, before the days of tourism and the high life of a ski resort.

On leaving Rome Dorothy had handed the responsibility for the Tea Rooms into the capable hands of Giulia, Anita and Crescenza, supervised by her cousin Laura Minervini. Together, with their determination and dedication they managed to keep Babingtons running. Their chief objective was to ensure that the Tea Rooms did not close.

The war had split Italy in half with little or no communication possible between the two ends of the country. In 1943, worried for the fate of the Tea Rooms in her absence, Dorothy decided to attempt the journey to Rome, but could get no further than Padova, where she found lodgings for her family in the nearby village of Strà. It was here that, in January 1944 Isabel, the last of the founders of Babingtons, died of pneumonia. From now onwards, all the responsibility and decision-making for the Tea Rooms would be on Dorothy’s shoulders.

Piazza di Spagna continued to be a focal point of city life throughout the Second World War. In December 1943 the magistrate Mario Fioretti was assassinated close by the Spanish Steps. He was involved in distributing the Avanti! newspaper, the official voice of the Italian Socialist Party. Incidentally, before founding his own newspaper and creating the Fascist party, Mussolini had been a Socialist himself and editor of Avanti! Under his leadership, the paper’s readership increased from 20,000 to 100,000.

In March 1944, a few days before the Via Rasella attack (in which 34 German soldiers were killed by partisans) two German soldiers were blown up while they were walking in front of the Spanish Steps. The windows of the Tea Rooms shook and it was feared that the force of the explosion might have damaged the walls of the building.

Babingtons stayed open every day and continued to welcome anyone who wanted to come in and have a cup of tea and a slice of cake. The desire to satisfy customers never flagged and despite severe shortages the cooks managed to produce food by adapting recipes to whatever ingredients they could find. They and the waitresses even brought their own meagre rations from home so that cakes and bread could continue to be baked. Inventive recipes evolved: bread made of potato flour, chestnut-flour cakes and biscuits, even the mythical scones were made from boiled potatoes, and condensed milk took the place of fresh milk which was un-obtainable. The quality of the service remained as polite and discreet as always, with privacy a priority.

Only for one day, indeed only for a few hours, did Babingtons doors remain closed and the rooms empty. That was the day the Allies arrived in the city and while much of Rome was celebrating their arrival, in the neighbourhoods where Giulia and Anita lived there was still shooting on the streets.

When Dorothy returned to Rome, she was delighted to find everything still in place for recovery to get underway—and recovery was needed because income had suffered, but that was minor damage in times of war.

Dorothy was the sole manageress of Babingtons and the sole parent of her children. A heavy burden she talks about in her diary. But she was a resolute woman full of enthusiasm who kept the ship sailing. She died in 1987.

A portrait of Isabel Cargill created by her husband, the Italian painter Giuseppe da Pozzo. It is ornating the tea rooms until today, as is his pastel portrait of a rather imposing looking Miss Babington. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Rome.

By the end of the 1940s, the area around the Spanish Steps was changing with haute couture workshops and boutiques opening. Piazza di Spagna became the stage for the extraordinary revival of the Eternal City. Thanks to Cinecittà, filmstars, paparazzi and La Dolce Vita arrived in Rome. The Olympic Games of 1960 gave the city another boost.

There were strong links between the world of the cinema and Babingtons. Dorothy, whose husband Attilio had been Metro Goldwyn Meyer’s European Director, collaborated as a costumist in various films shot in Cinecittà, as did her daughter Diana, while her son Leonardo worked as a camera man.

Actors shooting in Rome—Italian but above all foreign—met up in Babingtons in their spare time. There were Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor (without make up!) having breakfast, Peter Ustinov came for lunch, Claudia Cardinale at tea time. Charlton Heston, the protagonist of Ben Hur, and Robert Taylor of Quo Vadis? (both films produced by MGM) were at home at Babingtons. Valerio’s daughter Chiara played among the tables with Tony Curtis’s little girl. Audrey Hepburn was a regular client, who appreciated Babingtons super dark chocolate cake in particular. She first started coming to the Tea Rooms while filming Roman Holiday and remained a faithful client after she moved permanently to Rome. Shy, she would hide behind her scarves and dark glasses and always chose a corner table. Smiling and courteous, she was the exact opposite of a prima donna. Incidentally, in 2016, the children of Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn met for the first time, in the Tea Rooms, when the film Roman Holiday was shown in the Piazza to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Peck’s birth.

The success of American filming activity in Cinecittà in the 1950s introduced the phenomenon of film stars made in the U.S.A, together with celebrity parties, invasive press photographers (the infamous ‘paparazzi’) and new night clubs. Federico Fellini captured this new world for all time in his 1960 masterpiece La Dolce Vita. Fellini himself lived close by the Piazza di Spagna in via Margutta. He kept his distance from this life however, and would sit quietly in the Tea Rooms sketching. He always ordered hot muffins with ham and cheese. The film personalities who populated ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ chose to frequent Babingtons for a good reason. They knew it was a safe haven, protected from the paparazzi and from indiscreet attention.

During those years, the third generation at Babingtons came into action: Dorothy’s children Giampaolo, Leonardo, Valerio and Diana. They brought with them the energy of youth, managing to convince their mother that the menu needed to be reconsidered, with new dishes added: savoury dishes to be served for lunch as well as for breakfast. Cakes and biscuits were no longer enough to satisfy their clients and indeed it was the clients themselves to suggest these changes.

The 1960s saw the arrival on the scene of the ‘capelloni’ (the long-haired ones) with occasional violent confrontations between ferociously moralistic military conscripts and innocent proto-hippies, most of them foreigners. In the 1970s, the real hippies arrived and in the ‘80s came the punks. The Spanish steps became the place where you met up with friends. This, from decade to decade, gave rise to violent reactions from those who were outraged to see the Steps ‘inhabited’ by sellers of hand-made necklaces spread out on tatty pieces of cloth, by smokers of pot, by bare-foot dancers and by drunks. But even with the Beat Generation revolution taking place only a few metres from the door, Babingtons somehow managed to maintain its dignity throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Very quietly, however, something of this counter-culture did make its way into the Tea Rooms. Rome’s interpretation of the spirit of Pop culture arrived through the imagination and vision of the artists of the so-called Piazza del Popolo school, born in the city thanks to Mario Schifano, Giosetta Fioroni, Tano Festa and Franco Angeli. Novella Parigini, an habitué of Babingtons, was a pioneer of Pop Art, among the first to break away from tradition. There is a historic photograph of her with Giò Stajano (the first celebrity to come out openly as gay) and a model standing in the Barcaccia fountain in Piazza di Spagna at the end of the 1950s. It seems that this image inspired Federico Fellini’s celebrated scene with Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain in La Dolce Vita.

Not surprisingly, Babingtons became the meeting place for emerging artists of all kinds, from painters to actors and film directors arriving in Rome from all over the world. As it had been on its opening in 1893, the Tea Rooms became a centre for intellectual encounters, with artists making appointments with agents, art dealers, film producers and patrons of the arts.

During the twenty years from the middle of the 1950s to the mid 1970s, Dorothy’s grandchildren were born: Giampaolo’s son Francesco, Leonardo’s children Arabella, Marco, Lorenzo, Alessandro and Christian, Valerio’s daughters Chiara, Ottavia and Emanuela, and Diana’s children Kirsten, Alison, Rory and Fenella. Dorothy had handed over the management of Babingtons to her daughter Diana but she herself still made occasional visits to the Tea Rooms where she would scrutinise the general running of the establishment and sample various dishes to make sure that the original recipes were being respected and the quality was up to standard.

Because of its atmosphere and its clientele, Babingtons became a sort of show-case for the city. People arrived to see who else was there, and also to be seen themselves of course. As did the young actor and heart-throb Vittorio Gassman. Lea—in the Tea Rooms for forty years first as waitress and later as manageress—remembers ‘he used to come in wearing a broadbrimmed hat, wrapped in a tight light-coloured mackintosh. All the women followed him with their eyes. He would stop at the bar, drink a little something, chat a while and occasionally smoke a cigarette. Sometimes he stayed for a couple of hours, always with his intense gaze and his just-right smile. I never saw him sit down at a table.’

For years after the Colonels’ coup d’état in Greece in 1967, exiled King Constantine and Queen Anne-Marie would use the Tea Rooms as a kind of home from home, spending hours at their usual table receiving visits from friends and sympathisers.

In 1980, a Japanese gentleman arrived at Babingtons. He wanted to speak with the proprietors as he had a proposition to make to open a Babingtons English Tea Rooms in Tokyo. Flour and water in Tokyo tasted differently. Cakes, pastries and teas had to be adapted. Dorothy was now over seventy years old. Therefore, it was her daughter Diana who accepted the challenge to travel to Japan. The Tea Rooms was on the second floor of Tokyo’s famous Isetan department store, with the interior decoration exactly replicating the Rome Tea Rooms. The Babingtons experience in Japan lasted nearly twenty years until various factors gave rise to the decision to end the partnership and concentrate on the new challenges facing the Tea Rooms in Rome.

In the 1980s it was not only the punk invasion which transformed Piazza di Spagna. The square was now a pedestrian precinct and buses were no longer allowed entry; the colourful flower sellers’ stalls had disappeared. A new metro station was opened in a side alley leading onto the Piazza. This changed the nature of the Piazza in dramatic ways, as only a few metro stops brought the suburbs into the heart of the city. This ended the square’s splendid isolation by the lack of public transport. It did not take long for a metamorphosis to take place, with new shops catering for less expensive tastes taking the place of the historic luxury names, as the area around the Barcaccia fountain in the centre of Piazza di Spagna saw the mingling of all the social realities of the city. This time too, however, Babingtons refused to be influenced by the changes taking place outside its doors. Inside, the atmosphere and the menu remained the same although the selection of teas was gradually being widened. Clients were grateful that Babingtons at least had not succumbed to the revolution in tastes. Favourites continued to be served while the Tea Rooms were invaded by bands of young people, taking over most of the tables with their hot chocolate with whipped cream, cakes and even champagne. In those days smoking was allowed in the Tea Rooms and did not seem to upset anyone. Sandro Pertini, an assiduous client until he became President of the Republic in 1978, came to smoke his pipe at Babingtons. The writer Elsa Morante was another smoker at the tea rooms, sitting at her favourite table under the window. She would read and write notes for whole afternoons.

Fashion designers Valentino and Gianetti who, with their atelier close by, lunched in the Tea Rooms almost every day until they employed an English chef to cook for them. Liza Minelli escaped to the kitchen to avoid the fans who would collect by the door. The singer Robbie Williams also took refuge in the kitchen. Edy, who worked in the Tea Rooms until 2014, actually took the decision to close Babingtons doors against the chaos caused by his fans raging outside. She promised Williams she would make sure he came to no harm and comforted him in perfect English with the offer of scrambled eggs and bacon, carot cake and tea. Then she would let him escape through the back door. The same back door through which the anti-Fascists meeting in the third room were allowed to sneak out during the twenty years of Fascist rule.

Today it is Isabel’s great grandchildren, Valerio’s daughter Chiara Bedini and Diana’s son Rory Bruce the fourth generation of the family to manage Babingtons. They took over the running of the Tea Rooms in the 1990s, after serving their due apprenticeship behind the scenes.

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic has hit Rome hard. If you want unique places such as Babingtons to continue, visit the famous Tea Rooms at Piazza di Spagna and/0r buy some of their great teas online!

Airtight tin with Blue Lady scented green tea. Photo by Claudia Mauer Copyright © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna 23-25, Roma, Italy.

When they opened Babingtons Tea Rooms in 1893, Isabel and Anna Maria decided to create their own blend, one that could not be found elsewhere. Twinings in England provided them with three different teas: black teas from Darjeeling in India and Ceylon and Keemun black tea from China. The two women themselves mixed their own blend in the fourth room, at the far end of the Tea Rooms. Their desire was to offer something unique that could not be imitated.

At the end of the 1950s things were to change. Valerio said goodbye to an increasingly unsatisfactory Twinings and on the advice of his future father-in-law (CEO of a hotel chain) made contact with his trusted Woodhams tea merchants, who would be the only suppliers for Babingtons until 1990. Woodhams sent the chests of the three teas selected by Anna Maria and Isabel to be blended in Rome but some clients complained that their teas produced a slightly different flavour from the original Babingtons blend. Valerio decided to take time off from his architectural studies to go to London with some water from the Acquedotto Vergine (inaugurated in 19 B.C. by the Emperor Agrippa) which flowed through the pipes in the Piazza di Spagna, so that Woodhams could perfect the blend in London, to be sent over ready mixed. ‘I flew to London’ Valerio remembers ‘with a 5 litre jar of Piazza di Spagna’s water, to be sure the blend would be identical. In Woodhams’ enormous warehouse, together with Mr Richardson, we tried and tasted for three consecutive days until we reached the precise balance of flavour, colour and intensity’. Babingtons Special Blend was born.

Historic photo of Anna Maria Babington sitting in her famous Roman tea rooms. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna 23-25, Roma.

Babingtons teas can not only be purchased at the tea rooms at Piazza di Spagna 23-25 in Rome as well as online, but also at selected shops in Belgium, Germany and Switzerland. I have tried two great scented teas from Babingtons, both delivered in airtight tins. Blue Lady is a scented blend of green tea enriched with bits of pineapple and mango and flavored with natural aromas of strawberries, cherries, figs and rhubarb. The recommended infusion time for this delightful green tea is 2-3 minutes. Use 2-3 grams per 200 ml at a temperature of 80°-85° Celsius.

Never boil green tea water. If your green tea tastes bitter it is because you used too high a temperature and/or your infusion time was too long.

My second Babingtons tea was a White Passion, also delivered in an airtight tin. This scented Pai Mu Tan is a refreshing white tea ideal for summer, notably thanks to pineapple bits. Babingtons only use natural flavors. The subtle White Passion is scented with pear, peach and pineapple. This delicate blend offers the refreshment you need on a hot summer day.

For a fresh and sweet taste use 2-3 grams per 200 ml. On my tin, Babingtons recommends an infusion time of 3-5 minutes at a temperature of 90° Celsius; they offer different and in my opinion wrong info on their website which, therefore, I will not mention here.

Never use sugar and/or milk with green or white teas, especially not with these delicate blends called Blue Lady and White Passion from Babingtons; I wrote those lines before I read Carla Massi’s book: Babingtons, the First 125 Years. A Roman Tea History narrated by Carla Massi. Sugar and milk would just ruin the subtle flavors. Many people put sugar and milk in teas because they boil the water and/or use infusion times which are too long or keep the tea leaves in the water permanently. Sugar and milk then help to get over the bitter taste. Green and white teas prepared correctly never taste bitter.

Historic photo of Ms. Babington. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna, Rome.

A look at the green tea leaves used for the Blue Lady blend. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna 23-25, Roma.

A look at the Pai Mu Tan leaves used for the White Passion tea. Photo © Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna 23-25, Roma.

Historic photo of Babingtons at the bottom of the Spanish Steps in Rome. Photo copyright ©: Babingtons Tea Rooms, Piazza di Spagna 23-25, Roma.

The main source for this history is the publication by Carla Massi: Babingtons, the First 125 Years. A Roman Tea History narrated by Carla Massi, Rome, Babingtons Tea Rooms, 2018, 125 pages.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations from the monograph reviewed here are not put between quotation marks.

Teapots at Amazon UK Teapots at Amazon US

White teas at Amazon UK

White Teas at Amazon US

Review added on August 1, 2020 at 00:02 Roman time.