Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) died from an overdose of heroin before his 28th birthday. Nevertheless, during his short life, he managed to create over 1000 paintings and objects as well as some 3000 works on paper and enter the art pantheon. In the 21st century, his star has been rising further. Here a look — in chronological order — at five exhibitions and their respective catalogues published by Hatje Cantz between 2010 and 2023.

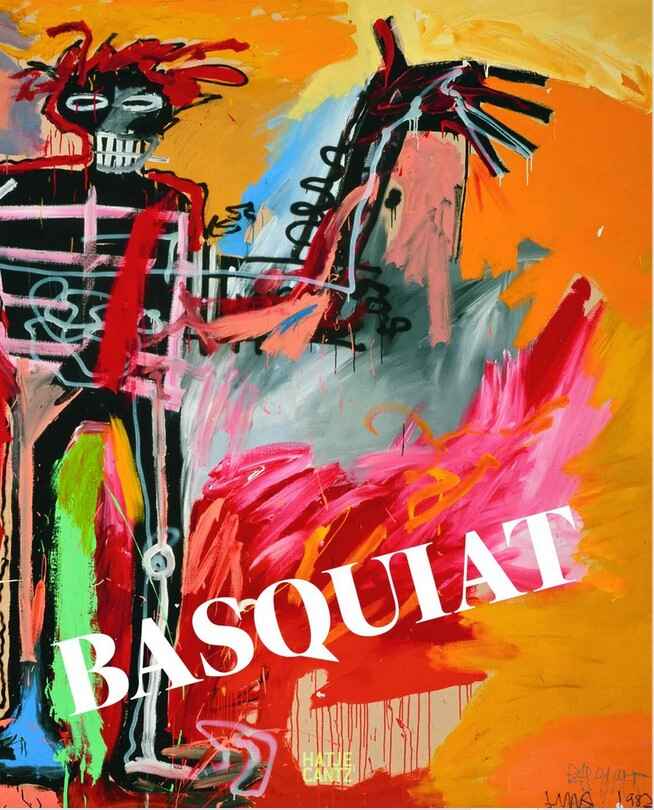

In 2010, I had the chance to visit the Basquiat retrospective at Fondation Beyeler (224-page English catalogue Hatje Cantz: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de), the first ever comprehensive show devoted to him in Europe.

Between 1977 and 1979 Basquiat, in collaboration with Al Diaz under the pseudonym of SAMO© (an abbreviation for “same old shit”), the teenager built a reputation in downtown Manhattan for his conceptual graffiti—poetic and frequently critical slogans. Subsequently, in a career spanning less than a decade, he collaborated with artists such as Francesco Clemente, Fab 5 Freddy, Vincent Gallo, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry, Madonna (his partner for a short time) and Andy Warhol. In 1982, Basquiat became the youngest artist ever to be invited to the prestigious Documenta in Kassel. The same year, Ernst Beyeler invited the 21-year-old artist to show his work at his gallery in Basel. He was not only represented by four paintings in the Expressive Painting after Picasso exhibition but, in addition, one of his works illustrated the catalog cover.

Furthermore, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s dealer was the Swiss Bruno Bischofberger, who introduced the young artist to Andy Warhol and suggested a collaboration with both Warhol and Francesco Clemente. Plenty of reasons to mount a Swiss exhibition.

The 2010 catalogue traced Basquiat’s development based on over 150 paintings, drawings, and objects spanning from the Anti-Products and the graffiti-influenced early works, through the painterly pictures and graphic word paintings, the silkscreens and collaborations with other artists, down to the late work with Basquiat’s premonitions of his own, premature death. They were presented alongside masterpieces by his idols and forerunners such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and Cy Twombley (all from the Fondation Beyeler).

Glenn O’Brien (1947-2017), the writer, critic, member of Warhol’s Factory and first editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine (1971-74), made together with Edo Bertoglio the film Downtown 81 (released in the year 2000), starrring Jean-Michel as himself. In his catalogue essay “Basquiat and the New York Scene 1978-82”, Glenn O’Brien portrays New York City, being broke back then, a new frontier, a no man’s land, full of drugs, anarchic enough to be congenial to the bohemian, a cheap city made for artists.

Glenn O’Brien underlines that Graffiti didn’t start out as art but it got artistic. Jean (he was “Jean” to his friends, not “Jean-Michel”—that came later) and Keith Haring were not graffiti artists, but artists using graffiti to get known. When Basquiat had his first one-man show, he still had tags in the Soho neighborhood and when word got around about the prices of his paintings, kids took SAMO© tagged doors of their hinges and stole them and dragged them into galleries in hope of a payday.

Glenn O’Brien writes that Minimalism and Conceptual art held sway, and young romantics, raised on Kerouac and Ginsberg and rock and roll did not feel particularly inspired by Donald Judd or Richard Serra. But they could relate to Leo Castelli. That’s where Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns showed their work.

Glenn O’Brien describes how there was an enormous boom in new galleries, taking up the vacant storefronts of Alphabet City. Soon the best artists of the alternative galleries would be plucked up by SoHo galleries, or the galleries themselves would move out from the hood because they had gentrified. The first big exhibition took place in an abandoned porno building on Times Square: the Times Square Show. Soon that art appeared in New York / New Wave, a big survey curated by Diego Cortez at P. S. 1 in Long Island City. Diego had traded in his own art practice for curation because he realized that just as the young artists needed their own galleries, they needed their own Henry Geldzahler. By 1981, there was a full-blown scene going on with new artists, new musicians, new filmmakers and actors, new writers and a new audience. Glenn O’Brien underlines that disco and punk happened simultaneously. He describes the daily racism, but also notes that this was a time and a place where you could be a hero and change the world in your spare time with a pencil. Jean did that.

In another essay, the Austrian art historian, critic, curator and Basquiat specialist Dieter Buchhart presents Jean-Michel as a revolutionary caught between everyday life, knowledge and myth, a radical both in his life and his work.

Keith Haring had dismissed the notion of Basquiat being a graffiti artist as erroneous. Dieter Buchhart underlines that indeed there is very little common ground, either in style or content, between SAMO© graffiti and works by his graffiti artist friends like Rammellzee, who himself attested: “Jean-Michel is the one they told you must draw it this way and call it black man folk art, when it was really white man folk art that he was doing. … They called us graffiti but they wouldn’t call him graffiti.” Dieter Buchhart writes that even the initial assumption that the pseudonym SAMO© was a cover for “a white conceptual artist” is an indicator of Basquiat’s diverging sphere of interests and different approach.

According to Dieter Buchhart, these early works not only offer a key to understanding the drawings, paintings, assemblages and sculptures Basquiat produced after 1980, but they also evidence his conceptual approach. In his essay, the art historian assumes that Basquiat’s first artistic phase lasted from the end of the 1970s until autumn 1981, culminating in Annina Nosei’s decision to make the basement of her gallery available to him as a studio.

His early paintings manifest the same immediacy and speed with which Basquiat executed his graffiti on buildings, as is documented in the 1980–81 film Downtown 81. Dieter Buchhart states that it was not until his painting Cadillac Moon (cat. 18) that Basquiat appeared to have decided on the formal erasure of his pseudonym by striking through “SAMO©” on the bottom left and inscribing “JEAN·MICHEL BASQUIAT 1981” opposite it on the bottom right. The art historian then compares the young man’s art to works by John Cage, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and others.

One detail: the 2010 catalogue erroneously dates Basquiat’s The Field Next to the Other Road to the year 1981 (reproduced and dated on the double page 50-51). The 2023 Fondation Beyeler catalogue Basquiat: The Moderna Paintings (check below) corrects this error, correctly dating this outstanding work of art to 1982.

This and much more, including a Basquiat interview, a chronology and a contribution by the American art critic, curator, painter and writer Robert Storr, can be found in the 2010 Fondation Beyeler exhibition catalogue.

Basquiat, Fondation Beyeler, Hatje Cantz, 2010, 224 richly illustrated pages. Order the English catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr.

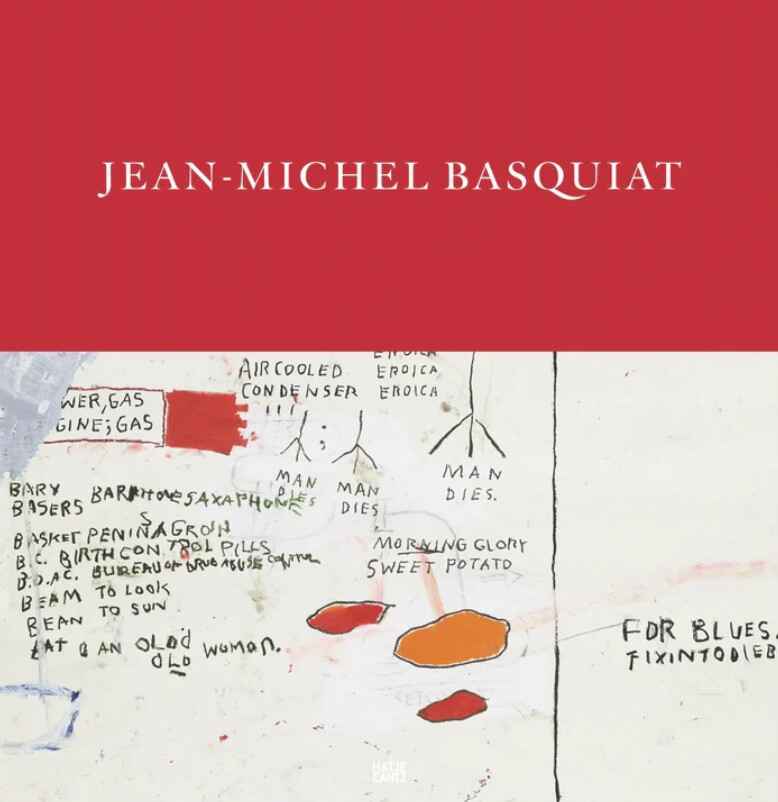

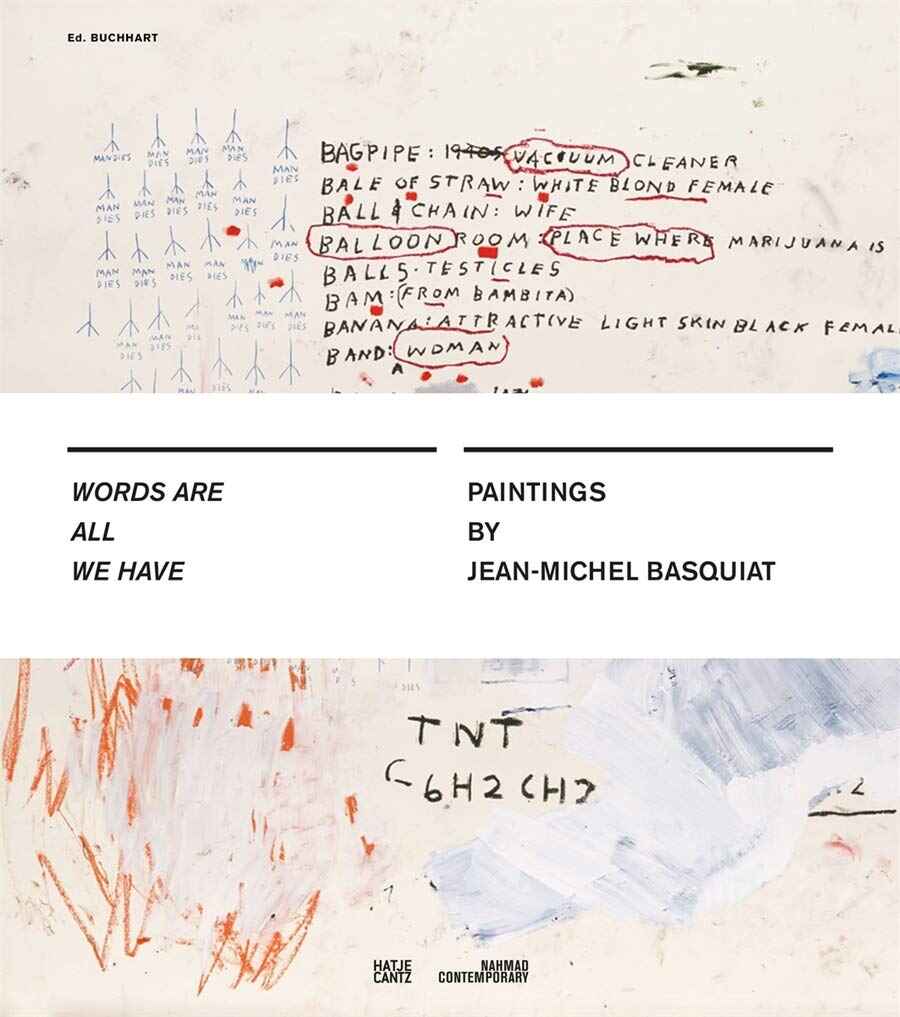

Dieter Buchhart curated the exhibition Words Are All We Have. Paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Nahmad Contemporary art gallery in NYC from May 2 until June 18, 2016 (English catalogue, edited by Dieter Buchhart, with essays by six authors, 215 pages, published by Hatje Cantz: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de).

In his catalogue contribution, Dieter Buchhart stresses that the use of language was part of Basquiat’s artistic practice from his very first drawings to his poetically conceptual graffiti, and from his notebooks to his later drawings and paintings. He turned to letters, words, numbers, lists and phrases as artistic material. He used words like brushstrokes because he loved words for their sense, for their sound and for their look (Klaus Kertess, “The Word,” in Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Notebooks, ed. Larry Warsh, New York: Art + Knowledge, 1993).

Dieter Buchhart notes that, in his paintings, the combination of pentimento, acrylic, oil pastels, and collage resulted in a form of painted hip-hop. Music producer, Greg Tate noted that Basquiat was “hip-hop’s greatest contribution to modernism (and vice versa).” According to Dieter Buchhart, the comparison is justified in that Basquiat had a great interest in music, worked at various Manhattan clubs as a DJ, participated in rap collaborations and created noise music along with Nicholas Taylor and Michael Holman in their band Gray. Furthermore, this comparison is emphasized by the fact that his works virtually challenge the beholder to rap to them. Drawing on his musical interests, he produced a series of paintings that explicitly referenced his musical heroes, such as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie or Duke Ellington.

Dieter Buchhart stresses that Basquiat’s work Now’s the Time, a round wooden disc with a diameter of 2.35 meters, forms the basis for a monumental homage to Charlie Parker and his 1945 jazz composition “Now’s the Time.” The heavy support becomes itself an oversize representation of a record, which Basquiat alludes to with two concentric circles in oil pastel after painting the wood disk black. He notated the composition title with a copyright symbol and the soundless abbreviation of the artist’s name P R K R without vowels on the record. In so doing, the letters and squeezed-out words remain the subjects of the painting, and, like Discography (Two), form a concrete hip-hop poem. Perceiving himself “not as a painter, but as ‘writer’ of tables, lists and vocabulary books,”Basquiat lists the discography of a jazz recording in the work Fats II (1987).

According to Dieter Buchhart, Basquiat was never interested in painting per se. His works are always borne by the polyvocality of postmodernism in the sense of polymorphism as a key paradigm of modernity. For example, in Untitled (Oreo) (1988) (plate. 21) the artist plays against the strong green background of the canvas, “like a giant notebook page”, with the ambiguity of the word O R E O and the monumental impact of the concept. Here, still according to Buchhart, Basquiat was possibly referring to the logo of the American cookie (fig. 14) that consists of two black wafers with a white filling, while simultaneously referring to the idea that “in the African-American community . . . an Oreo is used as a racial slur to insult blacks who ‘act white’ or identify as such.” The logo of the double cookie thus becomes perhaps a hiddenself-portrait, since Basquiat was accused of adapting to the white art world.

In her catalogue contribution, Jordana Moore Saggese writes that, in many of his works, Jean-Michel Basquiat combined expressive, gestural painting with abundant elements of text and language, willfully conflating the verbal and the visual.

Basquiat himself said: “I cross out words… so you will see them more: the fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them.” In her catalogue essay, Jordana Moore Saggese notes in this context that the precarious balance between concealment and revelation bears a striking resemblance to twentieth-century conceptualizations of the complex relationship between the authority of language, the nature of existence, and questions of truth—concepts all addressed in different ways by Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Martin Heidegger, and Jacques Derrida. In crossing out words so that we notice them, Basquiat similarly puts textuality—in thought and language—into question.

Jordana Moore Saggese argues that Basquiat manipulated language in an effort to break hierarchies of fixed meaning in texts and images—what Gates has called “chiasmus”—specifically in relation to black representation. Via the crossing out of certain words on his paintings and drawings, Basquiat highlighted his own doubts about the authority of language. Erasures and revisions of the word “slave” in his work The Nile (1983) (fig. 8), for example, indicate his concern with the black subject who is hailed into existence via the assignment of language.

Jordana Moore Saggese underlines that more than a dissolution of the boundaries between the verbal and the visual, the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat mobilizes text in an effort to underscore the failures of both language and image to represent experience. Rather than falling somewhere “between”expressionism and conceptualism—representing somehow a diluted version of one or the other—Basquiat’s practice embraced conceptualist practice in ways that critics have heretofore overlooked. Basquiat’s concern with the status of the object, the exploitation and commodification of the art world and the effects of language on subjectivity clearly situate him within a history of conceptual art.

Jordana Moore Saggese argues that, similar to the striking out of text to highlight doubts about the authorityof language, Basquiat employed gesture and other markings of expressionism as a form of critique rather than as a celebration of beauty or transcendence. She quotes the historian Georges Didi-Huberman: “If the image is what makes us imagine, and if the (sensible) imagination is an obstacle to (intelligible) knowledge, how then can one know an image?” According to Jordana Moore Saggese, perhaps this is what lies at the core of Basquiat’s practice. As we oscillate between imageand text, we enact the precariousness of knowledge itself.

These are just a few take-aways from the catalogue Words Are All We Have. Paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Nahmad Contemporary, 2016, 215 pages. Order the English catalogue, edited by Dieter Buchhart, with essays by six authors, published by Hatje Cantz, from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

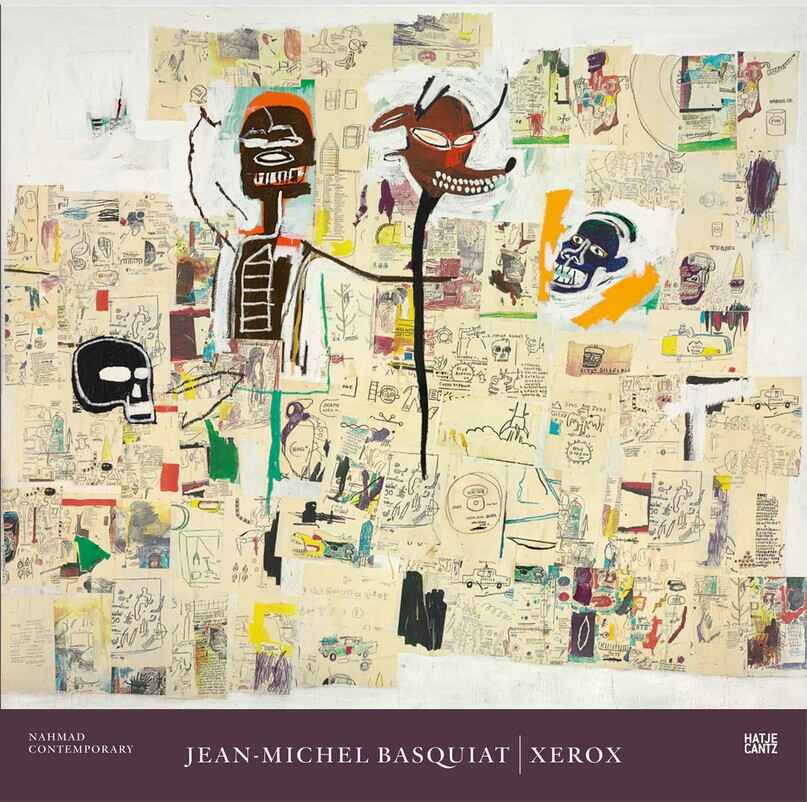

From March 12 until May 31, 2019 the Nahmad Contemporary gallery presented the exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat | Xerox (English catalogue Hatje Cantz: Amazon.com, Amzon.co.uk, Amazon.de). On show were over 20 works, in which the artist used photocopies as his principal medium and compositional focal point, accompanied by a trove of his earliest Xeroxed postcards.

The exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat | Xerox focused on the possibilities offered by the Xerox machine, as it allowed the artist the unlimited use of motifs from his visual lexicon as well as the ability to readily pilfer preexisting imagery from his surroundings.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s first foray into Xerox art was a series of small, colorful collages created in 1979 together with the then 20-year-old Jennifer Stein (aka Jennifer von Holstein) that incorporate paint splatters, scrawled text, and found detritus—from candy labels to newspaper clippings—, which they photocopied, mounted and sold for $1 as art postcards on the streets of New York.

The catalogue states that it was not until 1983, however, when collage became a defining element of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s artistic practice. He began to extensively use the Xerox photocopier as a creative tool. He called upon the cut-up technique popularized by Beat Generation writer William S. Burroughs to assemble cut-and-ripped photocopies of original and found imagery (including book reproductions, photographs as well as his own works on paper) into large-scale compositions that he overlaid with text, symbols, paint and drawings.

Basquiat’s raw, immersive, collaged paintings recycled and transformed signs and markings from his everyday experiences as well as motifs from earlier works into new forms. His style fuses expressive gesture, idiosyncratic figuration and poetic language. Throughout his practice, he tirelessly innovated his methods of creation, working beyond traditional means of painting, drawing and sculpture. Photocopying became so integral to his work that he eventually invested in his own color Xerox machine for his studio.

His Xerox paintings presage the copy-paste sampling of the Internet age and, at the same time, demonstrate an unprecedented self-appropriative technique that places him within the annals of conceptual art.

My favorite work of the Xerox exhibition was the Untitled (Coca Cola) from 1982, oilstick and xerox collage on metal, 71 x 51 cm. With the “Drink Coca Cola” logo on top, the collage could easily be mistaken for a Warhol, if the artist had not painted his signature “crown” over the logo.

Jean-Michel Basquiat | Xerox, Hatje Cantz, Nahmad Contemporary, 2019, 200 pages, with contributions by Dieter Buchhart, Christopher Stackhouse and Eric Robertson. Order the English catalogue from Amazon.com, Amzon.co.uk, Amazon.de.

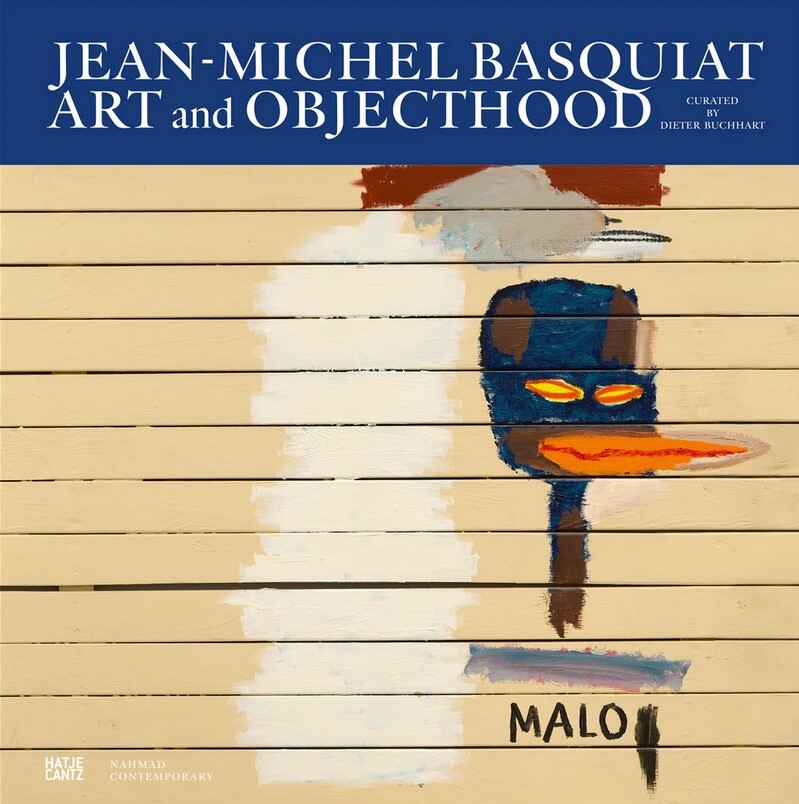

From April 11 until June 11, 2022 the Nahmad Contemporary gallery in New York City showed the exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat: Art and Objecthood (catalogue Hatje Cantz, 284 richly illustrated pages, with essays by Dieter Buchhart, Ben Okri and J. Faith Almiron: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de).

Curated by Dieter Buchhart, the show focused on the artists sculptural practice, presenting a wide range of unconventional painted supports and found-object sculptures. From subway tiles in his earliest works to discarded windows, doors, mirrors, wood boards, cabinets, chairs and refrigerators, Jean-Michel Basquiat used almost whatever he could find for his paintings and drawings.

The Nahmad Contemporary exhibition and catalogue borrow their title from the 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood” (Artforum 5, no. 10, Summer 1967, pages 12–21) by the American art critic and art historian Michael Fried (*1939 in NYC). In the catalogue, Dieter Buchhart explains that Michael Fried turned against minimalist dogmatism and spoke in favor of an artistic practice more in the spirit of Robert Rauschenberg, whom the minimalist artist Donald Judd criticized for creating his paintings and sculptures “part by part, by addition.”

Michael Fried defined “art” and “objecthood” as two opposing forces, whereby “art” stood for autonomous form, separated from its surroundings, a structure organized on its own. With “objecthood,” Michael Fried referred to an antithesis to art, which is why for the art historian the objects of the minimalists embodied an objection against their character as art. To defy painting and sculpture, minimalist art is made up of parts and establishes relationships between them to emphasize the one single form and simple totality of the object in a seemingly theatrical way. In short, Michael Fried criticized Minimalism for its dogmatic separation between “art” and “object,” arguing that its presentation of isolated objects as art was theatrics rather than a true art, which for Michael Fried implied the unity of art and object.

Dieter Buchhart writes that the neo-expressionists of the late 1970s and 1980s understood themselves as a countermovement to minimalism and conceptual art, a liberation from its formal and conceptual rigor. In addition to rejecting minimalism’s opposition to the idea of the artist as genius and obliteration of the artist’s signature, the neo-expressionists rejected the concept behind an artwork—preliminary texts, designs, and sketches—taking on a life of its own, as was typical of conceptual art.

For Dieter Buchhart, this is interesting because Basquiat is usually classified with artists like David Salle or Julian Schnabel under the category of neo-expressionism, which, with terms like “bad painting,” “new image painting,” or “wild style,” was considered a countermovement to conceptual art. Already by the late 1990s, Basquiat was placed in relation to neo-expressionism, while Dieter Buchhart has focused in his writing on the conceptuality of Basquiats works. Dieter Buchhart then asks to what extent did Basquiat differ from a neo-expressionist approach? How can his relationship to conceptualart be defined? And what position do Basquiat’s objects and assemblages take in the field of tension between “art” and“objecthood”?

About the various supports the artist used, Dieter Buchhart notes for instance that, for his early object-like works, Basquiat used both discarded doors and doors that were still in use in his own apartment or his friends’ homes as three-dimensional painting supports. Or, in Los Angeles, Basquiat discovered wood slats as another form of three-dimensional visual support when he was about to fix his garden fence. Fred Hoffmann wrote: “The back door of the studio opened onto a small courtyard, which was enclosed by an eight-foot-high, deteriorating slat wood fence. . . . Having made plans for the disposal of the wood fencing material, Jean-Michel instructed that the now deconstructed fence be brought into the studio. Within a day or two, the wood slats started totake on a new life. Using longer sections of the wood fencing asvertical support elements, the artist instructed his assistants to stack the individual wood slats horizontally, thereby turning the fence material into new, unique picture support.” Back in NewYork, Basquiat continued working with wood slat objects in various forms.

Dieter Buchhart writes that the years 1986 to 1988 were particularly marked by an oscillation between accepting and evading the void. During this period, Basquiat continued his exploration of the assemblage. For the triptych Negro Period (1986, plate 29), he used a shipping box as a three-dimensional support, emphasizing its objecthood by painting its sides with a geometric pattern in dark blue, orange, red and yellow. As a kind of ornamentation on the left and middle panels, a line of bottle caps is arranged around two fields of allover collages of Xeroxes. On the middle field,B asquiat drew an empty circle, which not only is a symbol of infinity but also is the visual language of the homeless—as noted in Henry Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook, it means “nothing to be gained here” in the hobo code—and a symbol that the artist would frequently refer to in the years to come. The right panel, which can be moved on two hinges, is reserved for the schematic depiction of a Black man, over whose head a kind of sutured wound is added, alluding to the battered body of the tormented, tortured and exploited slave.

At the beginning of his catalogue essay “Seven Meditations on Basquiat”, Ben Okri notes that Basquiat’s art is the art of possession. It is the ritualizing of presence. Its essential source is a primal belief in the power of images and words. And words, in a painting context, are images too. Other take-aways from his contribution include the statement that Basquiat was essentially an artist of possibilities, or that Basquiat always saw objects as ritual receptacles of images, that is to say energy. We also learn from Ben Okri that the last time Basquiat used his trademark crown was in Riddle Me This Batman (1987, fig. 8) — and the crown is upside down.

The performance artist and cultural studies scholar Johanna Faith Almiron writes in her catalogue essay about the dissonance between how the elite art world and wealthy class treated Jean-Michel Basquiat—a Black and Latinx youth from Brooklyn—when he was alive versus the present moment. According to J. Faith Almiron, Basquiat probed the very system that extracts and manipulates Black genius and the people who profit from it, from the corporate collectors who will pay anything to authenticate forgeries to the scholars who ensure that transaction; as well as from the curators who attempt to possess Basquiat as if he is territory to be claimed to the playwrights and screenwriters reinventing narratives with bold conjecture. Not unlike Basquiat’s favorite jazz and bebop musicians, such as Miles Davis and Charlie Parker, who were applauded on stage but could only enter venues through the back door, Basquiat navigated the same ocean of white sharks.

For J. Faith Almiron, part of the genius of Basquiat was his capacity to engage multiple modalities of knowledge and art production. Defying constructed binaries between high and low art or the art histories of the West and the Rest of the World, Basquiat synthesized all of the above in simultaneity and with surety. He did this through rigorous interdisciplinarity in his practice, method, and subject matter.

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Art and Objecthood, Nahmad Contemporary, Hatje Cantz, 284 richly illustrated pages, with essays by Dieter Buchhart, Ben Okri and J. Faith Almiron. Order the catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de.

From June 11 until August 27, 2023 the famous Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland showed the exhibition Basquiat: The Modena Paintings (English catalogue Hatje Cantz: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de).

Until the Fondation Beyeler exhibition in 2023, the eight large-scale Modena Paintings, created in the Italian Province of Emilia-Romagna in 1982, have never been exhibited together as a group.

But first a look back. From February 15 until April 5, 1981 at the New York / New Wave group exhibition presenting works by 119 artists, among them Nan Golding, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat (represented with 23 paintings and drawings).

Iris Hasler writes in Basquiat: The Modena Paintings that the New York / New Wave show was curated by Diego Cortez (an early Basquiat supporter) at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA PS1) in Long Island City. At this selling exhibition, the Italian painter and sculptur Sandro Chia directed the art dealer Emilio Mazzoli’s attention to Jean-Michel Basquiat and his work. Two other art dealers also took notice of the young man and bought some of his artworks: Bruno Bischofberger from Zurich and Annina Nosei from NYC.

At the time, Mazzoli’s gallery focused on Conceptual Art, Arte Povera and the Transavanguardia movement. Emilio Mazzoli worked with artists such as Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente and Mimmo Paladino, who were based both in Italy and New York.

In May 1981 already, Jean-Michel Basquiat had his first solo show ever at the Galleria d’Arte Emilio Mazzoli in Modena, back then still under the pseudonym SAMO© which had originated in his collaboration with the graffisti artist Al Diaz.

The 1981 Modena show was a disappointment: hardly anyone attended the opening, and the paintings were eventually bought by Mazzoli’s friends and acquaintances as a personal favor to the dealer. But it marked Basquiat’s transition from making art in public and private spaces to presenting it in galleries.

Iris Hasler writes that, shortly thereafter, Basquiat’s exhibition activity started to flourish. In late 1981, he participated in Annina Nosei’s group show Public Address, and she subsequently became his first dealer. Since Basquiat lacked a studio of his own, she made a workspace available in the basement of her NYC gallery. From March 6 until April 1, 1982 she organized his first solo exhibition under his real name and then arranged for him to have a further show, at the gallery of Larry Gagosian in Los Angeles. At the same time, the Italian curator Achille Bonito Oliva decided to include two paintings by Basquiat in his exhibition Transavanguardia: Italia/America at the Galleria Civica del Comune in Modena. In June 1981, at the invitiation of Mazzoli, Basquiat returned to Modena for a second solo exhibition at his gallery, once again with works to be painted on-site.

Mazzoli provided Basquiat with a space to sleep and to work as well as painting supplies. At the art dealers Modena warehouse, the Italian painter Mario Schifano had been working for years and left not only finished paintings, but also some large-scale blank canvases, which all measured at least 221 x 400 cm. They were larger than and unlike anything Basquiat had painted to that day. He signed all the works on the backside with his name and the addition “Modena”, which identify them as a cohesive group of works. The collaging of different images and words, which otherwise typifies Basquiat’s work, is almost absent from the Modena pictures.

Iris Hasler writes that after Basquiat had completed the eight paintings, the exhibition project was nevertheless not pursued further. This was due to an unfortunate clash of expectations. Whereas Annina Nosei, as Basquiat’s dealer, wanted to receive a percentage of the sales revenue, Emilio Mazzoli saw himself as the artist’s chief sponsor from the outset and consequently sought to claim the credit not only for organizing and financing the exhibition but also for Basquiat’s ongoing development as an artist.

Basquiat was unhappy with the plans his dealers had set up for the production of new works, which made him feel like a mere puppet of the art market, or, as he put it, a “gallery mascot”.

Iris Hasler notes that, contrary to Basquiat’s recollection, Bruno Bischofberger was not involved in the exhibition plans or even present in Modena, as the Zurich gallery owner and Mazzoli have both reported.

Before Basquiat left, somewhat hastily, to return to New York, Mazzoli paid him $30,000 for the eight paintings, which were never shown together in Modena. With Annina Nosei acting as intermediary, Bruno Bischofberger bought four of the works: Profit I, Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump, Untitled (Woman with Roman Torso [Venus]) as well as The Guilt of Gold Teeth. Iris Hasler writes that the other paintings found their way into various collections: Untitled (Devil) went to Japan, The Field Next to the Other Road was acquired by the art dealer Mario Diacono. According to Sam Keller, today all eight Modena Paintings are held in private collections.

In October 1982, the Galerie Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich opened the first of in total four Basquiat solo exhibitions mounted prior to the artist’s death. Of the works created in Modena in 1982, only Profit I was shown there. After Basquiat fell out with Annina Nosei, Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich became Basquiat’s exclusive international representative at the end of 1982, an agreement that lasted until the artist’s death.

As for the catalogue, in contains not only an essay by Iris Hasler and double-page reproductions of all eight Modena Paintings but also detailed descriptions and analyses of all works as well as additional illustrations and a chronology.

Last, but not least, I would add that, like Matisse, Jean-Michel Basquiat was a great colorist, which can be best admired on the catalogue double-page 108-109, which displays the eight Moderna Paintings on a black background.

Edited by Sam Keller and Iris Hasler: Basquiat: The Modena Paintings. Fondation Beyeler, Hatje Cantz, 2023, 120 pages. Order the English catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in these exhibition and catalogue reviews have not been put between quotation marks.

Book reviews added September 27, 2023 at 16:11 Swiss time. Updated at 18:28: Basquiat created over 1000 paintings and objects as well as some 3000 works on paper.