From April to November 1925, Paris showed the landmark Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, after which the term Art Déco was coined.

As early as in the summer of 1926, the City Art Museum in Saint Louis hosted the exhibition A Selected Collection of Objects from the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art at Paris 1925. Visitors in Saint Louis could discover almost 400 objects, including furniture, textiles, tableware and more. Subsequently, the museum purchased several pieces for the permanent collection.

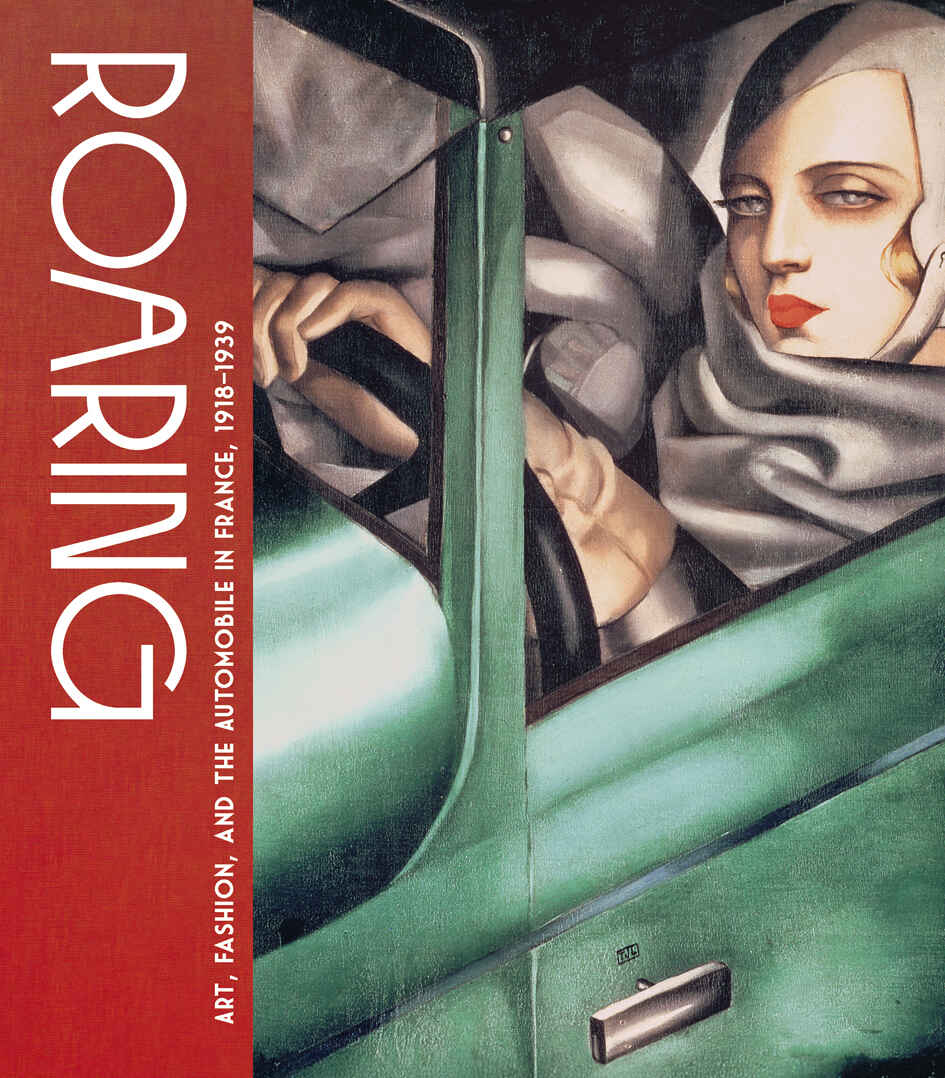

However, some object groups were missing in Saint Louis in 1926: cars and couture. One hundred years later, they are included in the Saint Louis Art Museum exhibition Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918-1939. From April 12 until July 27, 2025 the museum presents 160 works of art, design and film as well as 12 historical automobiles curated by Ken Gross.

The catalogue edited by Genevieve Cortinovis: Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918-1939. With contributions by Sarah Berg, Genevieve Cortinovis, Pierre-Jean Desemerie, Ken Gross, Justice Henderson and Daniel Marcus. Hirmer Publishers, 208 pages with 260 illustrations, 25,5 x 29 cm, hardcover. ISBN: 978-3-7774-4458-1. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Curated by Genevieve Cortinovis, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Associate Curator of Decorative Arts and Design, the Saint Louis Art Museum features exemplary French automobiles from the interwar period alongside works of art and women’s wear. Bespoke products from luxury brands such as Bugatti, Citroën, Chanel, and Schiaparelli meet innovative works of individual artists and designers to present a fuller picture of cultural exchange during the Art Déco period.

Roaring explores the automobile as both object and subject. In addition to ideas of progress and luxury, the show emphasizes the skilled craftsmanship evident in the automobiles of this period while also tracing the reciprocal influences of the avant-garde.

The Saint Louis exhibition looks beyond the interwar art scene in France and examines the wider creative ecosystem that connected artists, designers, architects, engineers, and manufacturers and enabled truly interdisciplinary innovation across fields. In addition, the show underscores the critical role of women and recent immigrants across all sectors of design in France during the Art Déco period.

In addition to essays by three museum staff members—Sarah Berg, Genevieve Cortinovis and Justice Henderson—, the catalogue offers three contributions by external authors—Ken Gross, Daniel Marcus, and Pierre-Jean Desemerie—each sharing their own research and perspective. The essays highlight the surprising connections between art, fashion and automobiles as well as the people who transformed them.

In her catalogue Introduction, Genevieve Cortinovis writes that Roaring considers automobiles as one thread in an interconnected web of creative disciplines strengthened by personal and professional relationships and shared materials, technologies, and approaches. It explores how users and observers, especially visual artists, expressed the car in motion, whether the thrill or quiet luxury of driving or the visual cacophony of the modern street. Featuring paintings, photographs, sculpture, furniture, films, fashion, textiles, and twelve automobiles, Roaring illuminates this rich creative ecosystem in which cars absorbed and influenced facets of modern art, design and architecture.

Genevieve Cortinovis notes that interwar France, Paris particularly, was a magnetic, global, artistic center. But she stresses that nearly half of the figures highlighted in Roaring were transplants. Sonia Delaunay and A. M. Cassandre were born in the present-day Ukraine; Sarah Lipska and Germaine Krull in Poland; Jacques Lipchitz in Lithuania; Ilse Bing in Germany; Eileen Gray in Ireland; Constantin Brancusi in Romania; Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in Switzerland; Joseph Figoni, Elsa Schiaparelli, Fernand Jacopozzi, and Ettore Bugatti in Italy; and Josephine Baker and Man Ray in the United States. Genevieve Cortinovis makes a mistake in her list, including Alberto Giacometti among the Italians instead of the Swiss.

Genevieve Cortinovis underlines that the automotive industry, centered around Paris, thrived in no small part due to the energy of émigrés. Conceived like compact rooms, automobiles exemplified ingenious storage and space-planning solutions, new technologies as well as modern travel. Materials and techniques moved fluidly between sumptuous Art Deco interiors and luxury automobiles. In car production, architects recognized the potential for standardization and mass manufacturing of unprecedented scale and complexity. Genevieve Cortinovis writes that painters, filmmakers and photographers discovered novel perspectives, subject matter and even canvases on and in cars

Celebrating the cross-disciplinary spirit of Roaring, the exhibition catalogue brings together essays from art, design, fashion and automotive historians. Daniel Marcus considers the surprising impact of closed-cab car design in upending the perceptions of the automobile in France following World War I. Centering Henri Matisse’s 1917 painting The Windshield, On the Road to Villacoublay, Daniel Marcus charts the transformation of the automobile from a Futurist vision of violence, power, and masculinity to a bourgeois product of middle-class comfort.

A great, iconic painting by Tamara de Lempicka (1898–1980), Self-Portrait (Tamara in the Green Bugatti), adorns the catalogue cover. This oil on panel from 1928, 13 3/4 × 10 5/8 in., is part of a private collection. The Polish artist Tamara de Lempicka was active in France and the United States and is an exemplary representative of Art Deco painting.

In his catalogue essay, Closed-Body Problems. Modernism, Gender, and the Esthétique de l’automobilem, Daniel Marcus underlines that, looking to changing codes of fashion, the French interwar industry sought to appeal to women consumers for practicality and comfort, identifying the simplification and rationalization of the car body with the streamlining of dress silhouettes. He notes that, just as French fashion expressed an increasingly androgynous ideal of liberal femininity, so too did modernism’s linear aesthetic suggest a parallel defeminization—and undomestication—of the family car.

According to Daniel Marcus, Tamara de Lempicka painted her Self-Portrait (Tamara in the Green Bugatti) for the July 1929 cover of the German magazine Die Dame. The artist’s figure merges seamlessly with the machine-picture assemblage, becoming yet another sharp-edged surface in an image world of metal and industrial varnish. Daniel Marcus quotes Tamara de Lempicka who remarked: “I was always dressed like the car, and the car like me”, framing the relationship between driver and vehicle as a sartorial tautology.

In her catalogue essay, Alfa Romeo, Robert Mallet-Stevens, and the Plastic Spectacle of the Modern Showroom, Genevieve Cortinovis examines the complicated and revealing position of the automobile at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris.

Another of her essays, Slow Work in Fast Times: Craft, Industry, and Technology at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, examines the role of the famous fair, which was initially conceived to foster collaboration between decorative artists and manufacturers and improve and increase French exports in the face of rising competition from Germany, whose architects, designers, manufacturers, craftspeople and retailers were successfully forging partnerships that brought modern, often machine-made, goods to middle-class consumers. Yet by the time the fair opened on April 28, 1925 its organizers had abandoned the focus on cross-industry collaboration. Instead, they sought to reaffirm the superiority of French luxury production and recenter Paris as an international leader in taste and fashion.

Genevieve Cortinovis states that Citroën and Delaunay-Belleville understood implicitly that the automobile industry would not flourish on the backs of engineers alone. Manufacturers needed artists and designers to endlessly reimagine the automobile of the future and capture the attention of easily distracted consumers in an increasingly competitive market-place.

In his essay entitled Custom Coach-Building in Interwar France, Ken Gross provides an overview of the history of custom coachwork in France with an emphasis on innovations and practices particular to the region. His essays on each of the twelve automobiles in the exhibition detail both their technical and aesthetic significance in the history of automobile design.

In his essay, The Elegant Racer in Interwar France and Her Fashion Glow, Pierre-Jean Desemerie explores the interconnected evolution of automobiles and fashion—from practical sportswear to the allure of shine—and the negotiation of gender norms as women became a key market for cars.

Woven throughout the catalogue are short essays by Sarah Berg, Justice Henderson, and Genevieve Cortinovis, spotlighting figures who shaped the look and perception of automobiles—from tools of self-expression and autonomy to symbols of commodification and desire—as they altered the fabric of daily life.

In interwar France, the automobile encapsulated the ambitions and anxieties of a society struggling to reconcile tradition with modernity in the face of powerful technological and social change.

The following 12 cars are exposed: 1923 Bugatti Type 32 “Tank de Tours”; 1925 Hispano-Suiza H6B Labourdette Skiff‑Torpedo; 1928 Citroën B14 Faux Cabriolet; 1927 Bugatti Type 35B Hellé-Nice Grand Prix; 1930 Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 Zagato Spider; 1931 Bugatti Type 41 “Royale” Weinberger Cabriolet; 1936 Le Corbusier Voiture Minimum; 1937 Delahaye Type 135MS Figoni et Falaschi Competition Court; 1937/1938 Delage D8-120S Chapron Cabriolet; 1936/1937 Voisin Type C28 Aérosport Coupe; 1938 Talbot-Lago T150C-SS Figoni et Falaschi Coupe; 1939 Bugatti Type 57C Vanvooren Cabriolet; 1939 Bugatti Type 57C Vanvooren Cabriolet.

This and much more can be discovered in the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue, edited by Genevieve Cortinovis: Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918-1939. With contributions by Sarah Berg, Genevieve Cortinovis, Pierre-Jean Desemerie, Ken Gross, Justice Henderson and Daniel Marcus. Hirmer Publishers, 208 pages with 260 illustrations, 25,5 x 29 cm, hardcover. ISBN: 978-3-7774-4458-1. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

This catalogue and exhibition review is based on the exhibition catalogue Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918-1939. For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this review are not put between quotation marks.

Catalogue and exhibition review of Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918-1939 added on July 7, 2025 at 19:13 French time. The names of the 12 cars added at 20:21.