Exhibition at Neue Galerie, New York City: March 10 - May 22, 2006.

Exhibition at The Phillipps Collection, Washington, D.C.: June 16 - September 10, 2006.

Exhibition at The Menil Collection, Houston: October 6, 2006 - January 14, 2007.

The works of Paul Klee (1879-1940) were considered “degenerated” (entartet) by the Nazis while they enjoyed an enthusiastic reception by key collectors and curators in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. The Klee art market in Europe nearly collapsed while his works were sought-after by the American art patrons Galka Scheyer and J.B. Neumann, the collectors Katherine Dreier and Walter and Louise Arensberg and last but not least by the Curator and Director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, Alfred Barr Jr. By the late 1920s, the Bauhaus teacher Klee was considered one of the leading artists within the European Modernist movement, often mentioned alongside Picasso and Matisse, according to the directors of the three museums showing Klee and America: Neue Galerie, New York City from March 10 until May 22, 2006; The Phillipps Collection, Washington, D.C. from June 16 until September 10, 2006; and The Menil Collection, Houston from October 6, 2006 until January 14, 2007 (exhibition catalogue: Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.co.uk).

Biography of Paul Klee

Paul Klee was born in Münchenbuchsee near the Swiss capital Bern on December 18, 1879. He was the second child of the Swiss singer Ida Marie Klee, née Frick, and the German music teacher Hans Klee, from whom he took the German nationality. He grew up in Switzerland where he graduated from literary grammar school in Bern in 1898. The same year, he moved to Munich where he studied at the private art school of Heinrich Knirr, subsequently at the Academy under Franz von Stuck, a Symbolist and Expressionist painter who was one of the leaders of the Munich Sezession. In 1901, he traveled trough Italy in the company of the sculptor Hermann Haller. In 1902, he returned to Bern where he worked as a violinist and art critic at the Bern Music Society. The same year, he traveled to Paris in the company of the journalist Hans Bloesch and the painter Louis Moilliet. In 1906, he moved with his wife, the German pianist Lily Stumpf, to Munich. The following year, their son Felix was born. In 1911, he began to keep a handwritten catalogue of all his work. In 1912, Paul Klee was represented with 17 works in the second exhibition of the Expressionist movement The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter). In 1914, he traveled to Tunisia with the painters Louis Moilliet and August Macke. Klee was drafted into the German army in 1916 and returned home in December 1918. In 1921, Klee began teaching at the Bauhaus, where he stayed until 1931. In 1931, he left the Bauhaus and took up a professorship at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts. The same year, the Nazis searched his Dessau apartment and, later that year, he was suspended form the Düsseldorf academy by the new Nazi appointed director. His position in Düsseldorf was officially withdrawn the following year. In 1933 together with his wife Lily, he returned to Bern where, two years later, he was diagnosed with scleroderma, a progressive disease that eventually proved fatal. In Germany in 1937, Klee’s works were targeted in Hitler’s campaign against Degenerated Art (Entartete Kunst) and stigmatized as the expression of “a sick mind”. Klee died in the Sant’Agnese clinic in Locarno-Muralto, the Italian speaking part of Switzerland, on June 29, 1940. It was and still is not easy to become Swiss; it takes time. Therefore, he died without having obtained the Swiss citizenship he had been looking for. Paul Klee left an oeuvre of some 10,000 works. By far the biggest Klee collection in the world is in Bern in the Museum Zentrum Paul Klee, built by the Italian architect Renzo Piano. It opened in June 2005 and hosts some 4,000 paintings, drawings, watercolors as well as archives and biographical material.

Klee and America

The first American exhibition of works by Paul Klee took place at the Galleries of the Société Anonyme in New York City from march 15 to April 12, 1921 as the gallery’s fourteenth exhibition. The Paul Klee Catalogue Raisonné offers a detailed exhibition bibliography (1921-2003), on which the detailed one in Klee and America (pp. 278-287) is based.

With over 60 works, Klee and America is the first substantial exhibition of Klee’s work in the United States since the 1987 Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The ongoing compilation of his body of work by the Klee Foundation in Switzerland for the nine-volume catalogue raisonné project revealed that many of the artist’s finest works were in American collections.

A look around the exhibition and its catalogue reveals masterpieces such as Der Angler (The Angler, 1921, MoMA, NYC), Hoffmanneske Geschichte (Hoffmannesque Tale, 1921, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC), Narr in Christo (Fool in Christ, 1922, private collection), Die Zwitscher-Maschine (The Twittering Machine, 1922, MoMA).

Several of his pivotal works were acquired and exposed shortly before and during the Second World War by the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City as well as (later) by The Art Institute of Chicago.

One of the first to discover Klee in America was the contemporary art collector Katherine Dreier, who founded the Société Anonyme in 1920, together with the artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Their gallery was the first in the United States to show Klee’s work. Art historians and dealers such as William Valentiner, Galka Scheyer and J.B. Neumann joined the enthusiasts to increase the artist’s reputation. Other outstanding collectors included Arthur Jerome Eddy from Chicago, Albert C. Barnes from Pennsylvania, Duncan Phillipps from Washington, D.C. and Walter and Louise Arensberg from Los Angeles.

Logically, the exhibition shows works with American provenance from museums and private collections. Some of them belonged to the famous architects Walter Gropius and Philip Johnson, both of course familiar with the Bauhaus tradition. The author Ernest Hemingway and the artists Alexander Calder, Mark Tobey and Andy Warhol are among the other famous previous owners of works by Paul Klee.

Klee and America, that is a one way relationship since Paul Klee, unlike many other famous artists, never dreamed of visiting the United States, “the land of cowboys and skyscrapers”, as Josef Helfenstein and Elizabeth Hutton Turner put it in the catalogue’s introduction.

In Klee’s body of work, one can only find two references to America and its culture: a single comment regarding a performance of Loie Fuller and a single rendering of Josephine Baker. It was up to the Americans to travel to Klee in Munich, to the Bauhaus in Weimar and later in Dessau.

Klee made his breakthrough in Paris already in the early 1920s. Around 1930, his artistic and economic future seemed to lay in Europe, at the Bauhaus and at the Düsseldorf Academy, with German museums, including the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, collecting his works and René Crevel having published a Klee monograph in France. However, American collectors became crucial with the accession to power by the Nazis in 1933.

In the 1920s, Galka Scheyer in California as well as Katherine Dreier and J. B. Neumann in NYC were the key figures to have Klee’s works travel across the Atlantic. In the 1930s, with the arrival of exiled Bauhaus artists and Surrealists as well as the art dealers Karl Nierendorf and Curt Valentin, the United States became both a key market for his work as well as an important forum for his artistic message. Today, over 10% of his total output, some 1,150 works are held in collections in the United States.

Why Klee appealed to Americans

Paul Klee offered a new approach, a childlike sensibility, humor and a new way of seeing things. He freed young American artists who wanted to leave behind the limitations of geometric abstraction and Surrealist narrative. The editors emphasize his lack of a single style, although anyone even superficially familiar with Klee can easily recognize his works. They are however right in pointing out that Klee paved the way for the Abstract Expressionist generation. Still, he remains a singular figure and this is his contribution: artists should find their own way and not imitate a famous master or a school. Unfortunately, we are still looking for a contemporary artist of his sensitivity.

The catalogue Klee and America

The recommendable catalogue offers articles on the early years of the relation between Klee and America from 1913 to the 1920s with contributions by Vivian Endicott Barnett and Michael Baumgartner and Osamu Okuda. Josef Helfenstein and Charles W. Haxthausen concentrate on the artist’s 1930s reception, breakthrough and rescue in the United States. Elizabeth Hutton Turner, Jenny Anger, Brandford Epley and Christa Haiml analyze Klee’s impact and legacy in the 1940s and 1950s as well as his influence on Josef Albers and Robert Rauschenberg. Sarah Eckhardt delivers a chronology of events. A list of his exhibitions in America and a selected bibliography complement this work of excellence.

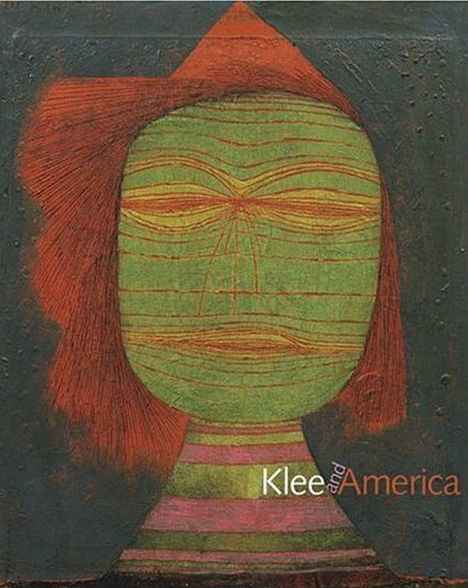

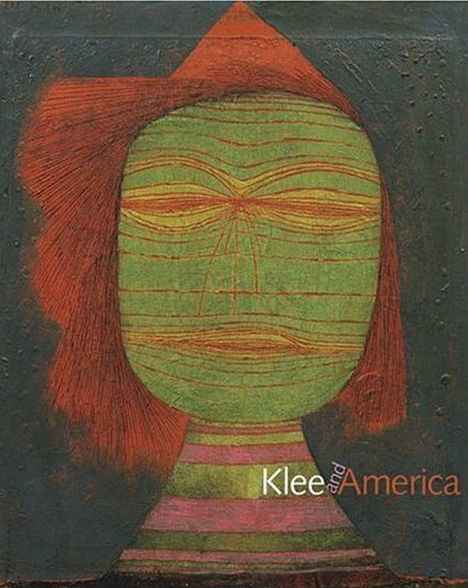

This article is based on the exhibition catalogue: Klee and America. Edited by Josef Helfenstein and Elizabeth Hutton Turner. Hatje Cantz, 2006, 316 p., 216 illustrations (97 in color). Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.co.uk. The book’s front cover shows Klee’s work Schauspieler=Maske (Actor’s Mask) from 1924, MoMA, New York.

Article added on July 19, 2006.