The bond between Frankfurt’s world-famous Städel Museum and the artist Max Beckmann (Leipzig, February 12, 1884 – New York City, December 27, 1950) is a very special one. For many years, Frankfurt am Main was not only home but also a source of inspiration to Beckmann. Already during his lifetime, the town citizens wanted his works in the Städel collection.

Thanks to Beckmann’s close friendship to then Städel director Georg Swarzenski, a large number of works by the artist – among them thirteen paintings – were purchased for the collection in the interwar

period. These Beckmann holdings, the largest in any German museum, were lost almost entirely to Nazi

iconoclasm in 1937. The confiscation of nearly all works by Beckmann within the framework of the Nazi “Degenerate Art” campaign represented a severe loss for the German museum.

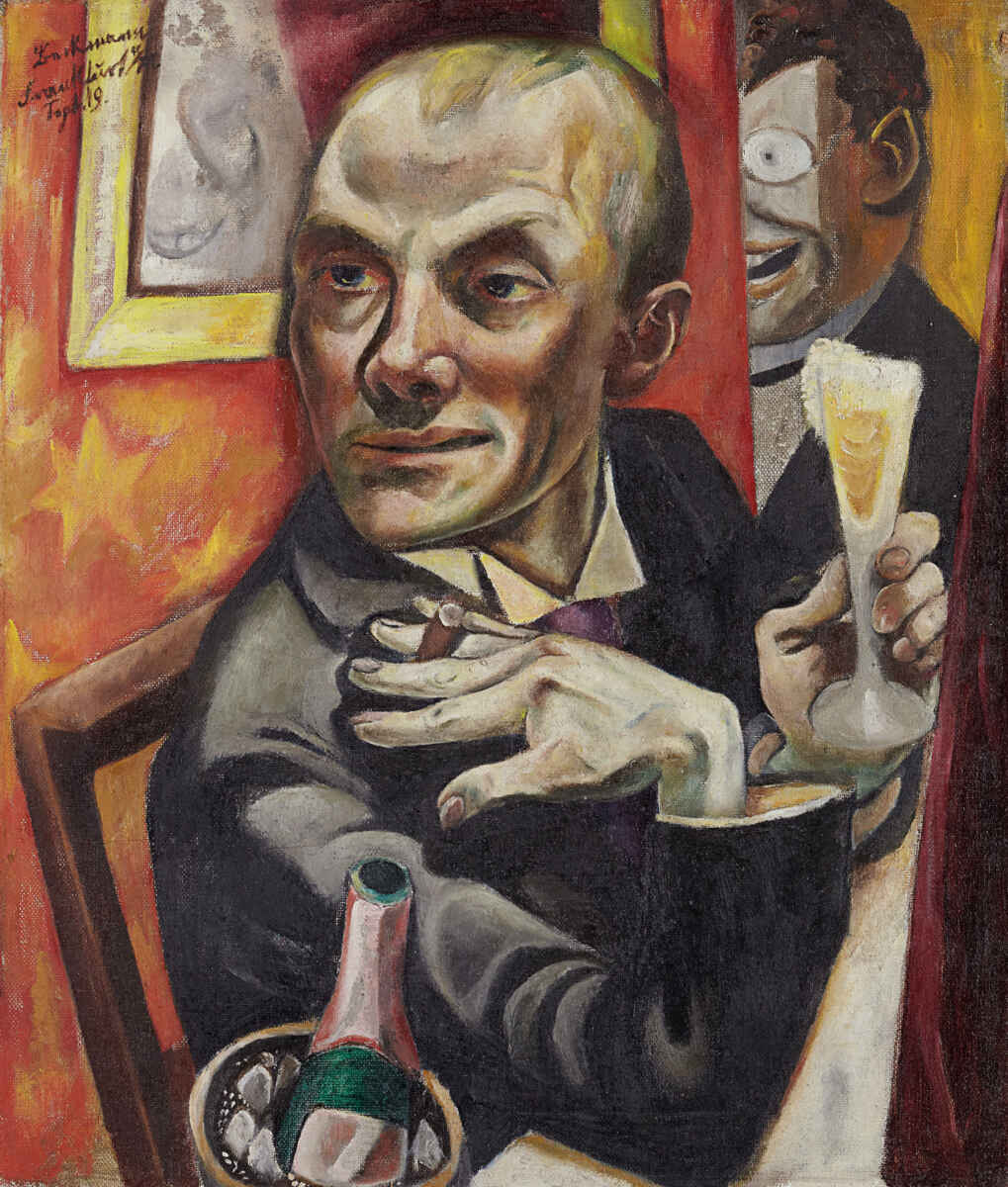

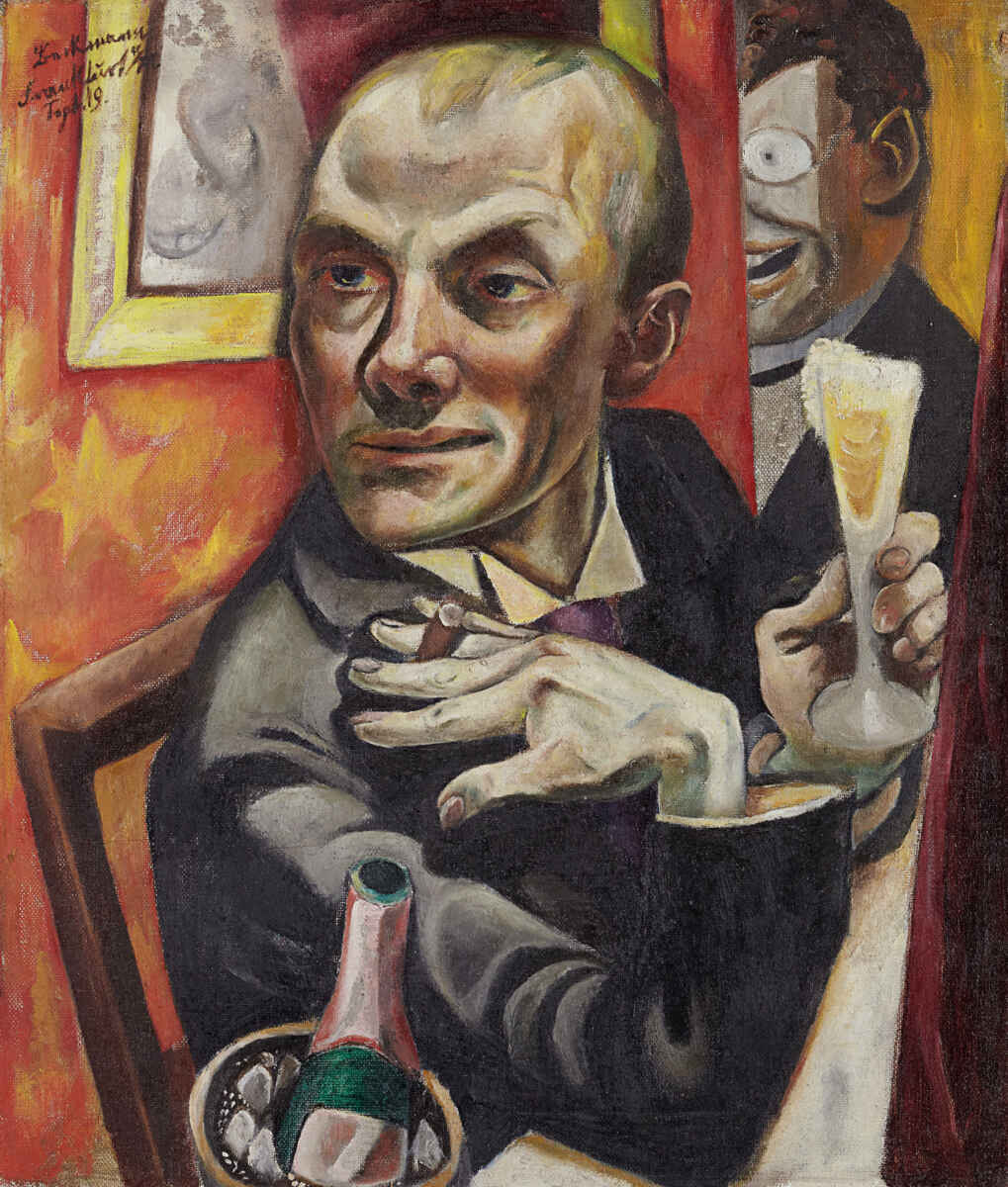

To compensate for this loss, the Städelscher Museums-Verein – the association of friends of the Städel Museum – devoted itself to the reconstruction of the modern art collection in the period following World War II. Since 1959, numerous Beckmann works have been purchased for the Städel, the latest being the masterpiece Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass (1919). It features prominently in the current exhibition Städel’s Beckmann / Beckmann’s Städel: The Frankfurt Years, ornates the catalogue cover and will remain permanently in the museum collection.

The Max Beckmann exhibition at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt is currently closed because of the covid-pandemic, but has been prolonged until August 29, 2021. The show is accompanied by a bilingual catalogue in German and English by Alexander Eiling, Regina Freyberger and Iris Schmeisser: Städel’s Beckmann / Beckmann’s Städel: The Frankfurt Years. This article is based on that 93-page book.

In his catalogue foreward, Philipp Demandt stresses that Max Beckmann spent the most formative years of his career – 1915 to 1933 – in Frankfurt am Main, where his works were featured in eighteen solo and group exhibitions as well as in numerous articles in the leading newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung.

Beckmann came to the city on the Main in 1915 to take temporary shelter in the home of his friends Ugi and Fridel Battenberg. He stayed until 1933, when the Nazis forced him out of his teaching position at the Frankfurt Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts).

Between 1918 and 1932, then Städel director Georg Swarzenski (1876–1957) purchased thirteen paintings as well as over one hundred drawings and prints by Max Beckmann. Nearly all of those works were lost to the Nazi “Degenerate Art” confiscation campaign in 1937. Thanks to numerous acquisitions since the postwar period, the Städel now once again owns one of the world’s most extensive Beckmann collections.

His many self-portraits served Max Beckmann not only to portray his personal frame of mind but, in addition, helped him define his role as an artist in society and served him as a means of addressing philosophical issues and fundamental human conflicts.

The Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass of 1919 with its shimmering palette, fragility and gripping ambiguity is a symbol par excellence of the incipient Weimar Republic. It shows Beckmann as an elegant dandy in a tuxedo at the bar of a nightclub. It marks the commencement of those Golden Twenties which were not so golden for many. The painting is an unsparing self-portrayal. It testifies to the deep trauma inflicted upon the artist by what he had experienced in World War I; he had volunteered as a medical orderly but returned disillusioned. At the same time, the painting is seemingly anticipating the horrors of the Nazi era with prophetic foresight.

The Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass of 1919 was part of the private collection of Hermann Lange from 1928 onwards. After the death of the Krefeld textile manufacturer and collector, the painting remained in the family’s possession until its purchase by the Städel Museum. It is therefore, for the most part, still in its original condition, with its old stretcher and an unvarnished surface that conveys the original colour effect of Beckmann’s palette. As a result, there is scarcely a work that exhibits the distinctive style Beckmann developed in his early Frankfurt years in as undistorted a manner.

The exhibition catalogue contains information regarding the collector Hermann Lange, Frankfurt places, personalities and institutions important for the artist and his development, the Städel’s Beckmann collection (acquisitions and losses), the relation between Städel director Georg Swarzenski and Max Beckmann as well as a discussion of past and present Beckmann works in the Städel collection.

Literature about Max Beckmann

Alexander Eiling, Regina Freyberger and Iris Schmeisser: Städel’s Beckmann / Beckmann’s Städel: The Frankfurt Years. Exhibition catalogue, Städel Museum, Frankfurt, 2020, 93 pages in German and English. Available at the museum’s shop and webshop.

Lynette Roth: Max Beckmann at the Saint Louis Art Museum: The Paintings. 2015, 272 pages, English. Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr.

Max Beckmann: Exile Figures. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, 2019, 210 pages, English. Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk.

Max Beckmann: weiblich-männlich. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Prestel Verlag, 2020, 240 Seiten. In German. Bestellen bei Amazon.de.

The photo which also ornates the book/catalogue cover shows Max Beckmann (1884–1950): Selbstbildnis mit Sektglas, 1919. Oil on canvas, 65,2 x 55,2 x 2,3 cm (without picture frame). Co-property of Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung, Bundesrepublik Deutschland and Städelscher Museums-Verein. Photograph copyright: Städel Museum.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations from the book reviewed here are not put between quotation marks.

Book / Catalogue review added on April 21, 2021 at 18:08 German time.