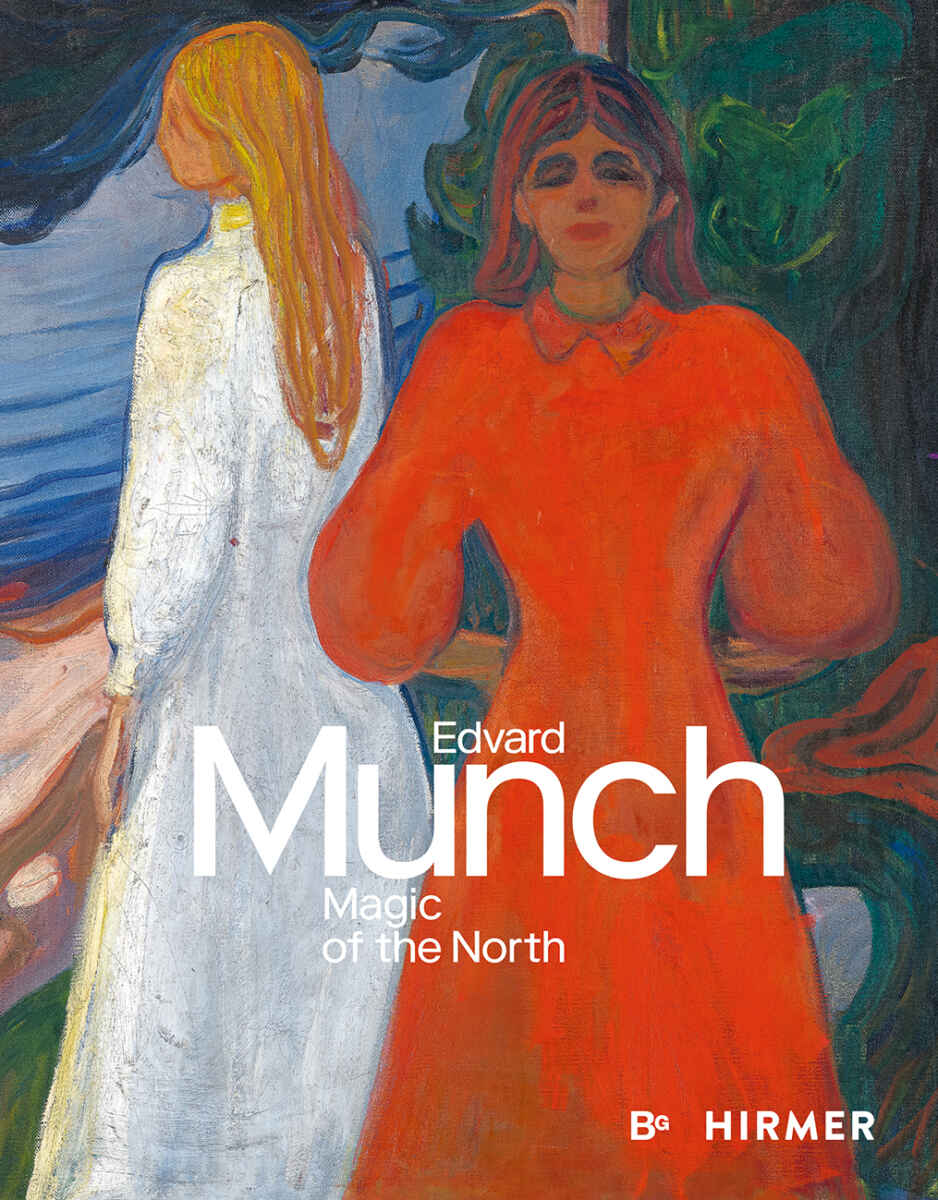

From September 15, 2023 until January 22, 2024 the Berlinische Galerie, Museum of Modern Art, at Alte Jakobstraße 124–128 in Germany’s capital Berlin presents the exhibition Edvard Munch: Magic of the North (accept all cookies to go directly to the catalogue’s Amazon page — we earn a commission: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr).

During his artistic career, Edvard Munch produced some 1,800 paintings and almost 750 prints with different motifs. During his lifetime, at least 10,000 copies of his prints were made in Germany alone, nearly all of them in Berlin. In collaboration with the famous MUNCH museum in Oslo, the Berlinische Galerie shows some 80 works by Edvard Munch, a key figure of European Modernism.

This show was organized in collaboration with the Munchmuseet in Oslo and marks the first cooperation between the Berlinische Galerie and the Museum Barberini in Potsdam.

Between 1892 and 1908, Edvard Munch lived in Berlin repeatedly for increasingly long periods, usually spending the spring and summer months in Norway. Berlin is where he got his international breakthrough thanks to a scandal.

In his catalogue foreword, Thomas Köhler, the Director of the Berlinische Galerie, tells the famous story about Munch’s rise to fame. In 1892, the artist accepted an invitation from the Association of Berlin Artists (Verein Berliner Künstler). The exhibition committee had “unanimously” approved the show at the recommendation of the Norwegian artist Adelsteen Normann, who had seen a Munch exhibition in Kristiania, present-day Oslo, and was enthusiastic about his colleague’s works of art.

Edvard Munch had previously been represented by three paintings in the Munich Annual Exhibition of Artworks of All Nations in the Royal Glass Palace (Münchener Jahresausstellung von Kunstwerken aller Nationen im Königlichen Glaspalaste), presumably made essentially the same selection for Berlin that he had made for his exhibition in Kristiania.

Thomas Köhler underlines that this invitation represented a great honor for the young Munch, since he would reach a larger audience than he had had in Munich and Oslo. The exhibition was scheduled to last two weeks, from November 5 to 19, 1892.

The sensation that the presentation of the 55 works in conservative Berlin caused was enormous. Thomas Köhler writes that influential circles around Anton von Werner, the director of the Royal Academic University of Fine Arts (Königliche akademische Hochschule für die bildenden Künste) and chairman of the Verein Berliner Künstler, initiated a wave of criticism. Adolf Rosenberg, an art historian and art critic who was a decided supporter of von Werner’s regressive view of art, wrote a devastating review in the newspaper Berliner Tageblatt and at the same time insinuated that even fellow artists had taken sides against the Norwegian painter.

Thomas Köhler underlines that, indeed, several members of the Verein Berliner Künstler did submit a proposal for the immediate closure of the Munch exhibition, and Anton von Werner called for a vote on the matter at a meeting of the members convened on November 12, 1892. The proposal was approved with 120 versus 105 votes. The morning of the following Sunday the Munch paintings were removed from the exhibition space. The conflict between the conservatives and the modernists made the artist famous far beyond Berlin.

Thomas Köhler stresses that despite these negative reactions (in fact because of these reactions), Edvard Munch remained faithful to Berlin for many years. From 1892 to 1933, he had around 60 exhibitions in Berlin, including at least 15 solo presentations. The Norvegian understood that the “Munch Affair” (Affaire Munch), the scandal surrounding his prematurely terminated exhibition at the Association of Berlin Artists, were the best possible promotion for his art. Edvard Munch wrote home: “That is, by the way, the best that can happen / I cannot get better advertising.” The 1892 show marked the beginning of modernism in the German capital and the start of Edvard Munch’s international career.

In her catalogue essay, Stefanie Heckmann writes that, in 1927, Berlin’s Nationalgalerie (National Gallery) showed what was then the largest ever exhibition by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch. It was also the largest exhibition yet for a solo artist in the modern department of the Nationalgalerie. Visitors could admire roughly 250 works from all the artist’s creative phases.

Stefanie Heckmann underlines that Munch’s emotionally condensed, intensely colorful visual worlds represented a “magic of the North” that was entirely a matter of course in Berlin in the 1920s, even though the Arcadia of the North was increasingly instrumentalized after World War I for an aggressive myth of Germania. Hardly anyone writing in the press about the triumphant retrospective at the Nationalgalerie failed to allude to Munch’s spectacular first appearance in Berlin in the late nineteenth century.

Stefanie Heckmann notes that, in Berlin, Edvard Munch found progressive intellectuals, artists, gallerists and collectors who appreciated and supported his work. He learned printing techniques in close collaboration with leading Berlin printing houses and began taking photographs.

In 1895, the art historian Julius Meier-Graefe published a first portfolio of Munch etchings accompanied by a text. Some fifteen years later, Curt Glaser, the responsible for the modern department of the Museum of Prints and Drawings (Kupferstichkabinett) in Berlin, began to assemble an extensive collection of Munch’s graphic work.

Stefanie Heckmann stresses that, in Berlin in 1893, Edvard Munch presented his paintings as a coherent series for the first time. He expanded this idea, which came to be essential for his work, in a Berlin Secession exhibition in 1902 to what he would later call his Frieze of Life.

Until 1933, when Hitler managed to be accepted as the leader of a coalition government and subsequently turned Germany into a dictatorship, Edvard Munch was taken for granted as part of Berlin modernism, even though he had returned to Norway in 1909. Stefanie Heckmann underlines that his presence in the city’s art scene changed the idea of the North. It was now associated with Munch’s works rather than with romantic or naturalistic landscape paintings of fjords.

Stefanie Heckmann underlines that Scandinavian authors such as Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, Ola Hansson and the Danish literary critic of Jewish origin Georg Brandes, whose works were sharply criticized and even censored in their own countries, found in Berlin niches and opportunities to publish and audiences for their plays, above all thanks to the Verein Freie Bühne.

In his catalogue essay, Lars Toft-Eriksen writes that the notion of the “magic of the North,” as Stefan Zweig put it in 1925, was no longer to be found in romantic or realistic depictions of wild and untamed nature, but in the psychologically dense work of writers such as Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, Georg Brandes and Knut Hamsun. According to Stefan Zweig, these authors were perceived as leading the way into new territories of the soul, and their literary work was seen as primal sources of hitherto unknown psychological problems.

Lars Toft-Eriksen mentions Edvard Munchs “Saint Cloud Manifesto,” written in Paris in 1889–90. The essay presents his artistic credo: “People would understand the sanctity and power of it and take off their hats as in a church.—I would create a number of such pictures. One shall no longer paint interiors, people reading and women knitting. They will all be people who are alive, who breathe and feel, and suffer and love.” Edvard Munch advocated the depiction of the invisible drama of the psyche, rather than the representation of outer reality. Lars Toft-Eriksen adds that, later on, Edvard Munch juxtaposed his credo with an aphorism from his notebooks, dated 1909–11: “The photographic camera cannot compete with the brush and palette—as long as it cannot be used in heaven or hell.”

The art critic Julius Meier-Graefe was affiliated with Munch’s group “The Black Piglet” (Zum schwarzen Ferkel), named after the Berlin tavern where they often met. Lars Toft-Eriksen notes that one may sense Baudelaire’s ideas in Meier-Graefe’s characterization of Munch as an artist. However, the influence of the French poet is far more distinct in the writings of the Polish writer Stanisław Przybyszewski, who befriended Munch in 1892 in Berlin.

According to Lars Toft-Eriksen, in his work On the Paths of the Soul (Auf den Wegen der Seele, 1897), Przybyszewski noted how the true artist, as a prophet, had to rise up against the injudicious “plebs [who have] always hated the soul.” Lamenting the lack of genius and the pitiful state of culture and arts under the reign of rationalism and naturalism, Przybyszewski claimed that only a few artists—Munch among them—gave promise of a true art envisioning the inner life of the soul.

In 1890, the Swedish playwright, novelist, poet, essayist and painter August Strindberg moved to Friedrichshagen, on the outskirts of Berlin, where he became acquainted with members of the radical group of poets and intellectuals called the Friedrichshagen Poetry Circle (Friedrichshagener Dichterkreis), which included members such as Richard Dehmel, Felix Holländer, Ola Hansson, Dagny Juel, Knut Hamsun and Stanisław Przybyszewski, but also notabilities such as Rudolf Steiner and Magnus Hirschfeld. Lars Toft-Eriksen notes that, after a short while, Strindberg moved to the city and gathered several of his acquaintances from Friedrichshagen at the wine bar Zum schwarzen Ferkel. Within these circles, Strindberg took on the task of disseminating new French poetry and aesthetic theory, including the writings of Baudelaire. Strindberg had spent considerable time in Paris avant-garde circles and befriended Paul Gauguin, among others. Baudelaire’s notion of the artist as a prophet of the soul was key to the French Symbolist group the Nabis (The Prophets), which were close to Gauguin.

After the Munch exhibition scandal in 1892, the art critic Julius Meier-Graefe defined a post-Romantic conception of the artist genius. In his essay, Meier-Graefe argues that the artist genius, like an apostle, protests the social conventions of his time. Like an anarchist, he seeks to turn the masses against their oppressor. Lars Toft-Eriksen underlines that Meier-Graefe is advocating an avant-garde notion of art, where the artist seeks a new world order through provocation and revolt, although he often times is being misunderstood by the public he is to lead.

After the National Socialists rise to power in 1933, Edvard Munch was instrumentalized as a Nordic, Germanic artist, but also defamed early on as “degenerate”, notes Stefanie Heckmann. Ten years after his triumph at the Nationalgalerie, 83 of Munch’s works were confiscated from public collections as part of the 1937 “Degenerate Art” (Entartete Kunst) action by the Nazis.

After Norway was occupied by German troops on April 9, 1940, the seventy-six-year-old Edvard Munch wrote his will and bequeathed all of his works, including his literary remains, to the city of Oslo. He hoped this would provide a place for his Frieze of Life and make his works available to a large public, according to Stefanie Heckmann.

One last word regarding Munch’s Frieze of Life. In her catalogue essay, Janina Nentwig writes that with the explicit identification of the works as a frieze—a “conveyor of sacred meaning” with a long tradition—the cycle of paintings acquired a quasi-religious charge. She underlines that many artists of the nineteenth century pursued similar ends, including painters Munch admired such as Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Ferdinand Hodler. But according to Janina Nentwig, Munch found in Berlin a concept that was very much his own, as complex as it was open. Whereas the individual works of The Frieze of Life capture the alienation of modern human beings, “the individual’s break with the world”, the frieze as a whole turns the loneliness and isolation into a circle in which life, with its hopes, disappointments and tragedies, is always beginning anew.

This and much more can be discovered in the truly great, beautifully illustrated and substantial exhibition catalogue Edvard Munch: Magic of the North. Edited by Stefanie Heckmann, Thomas Köhler, Janina Nentwig; with contributions by P. Behrmann, C. Feilchenfeldt, S. Heckmann, T. Köhler, S. Meister, J. Nentwig, A. Schalhorn, D. Scholz, L. Toft-Eriksen. Hardcover, Hirmer Publishers, 2023, 304 pages, 246 color illustrations, 21.7 × 28 cm. English hardcover catalogue (accept all cookies to go directly to the book’s Amazon pages — we earn a commission): Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr.

Further reading: article about the Munch : Van Gogh exhibition in Amsterdam.

Top Angebote und Aktionen bei Amazon Deutschland

Ventes Flash et promotion chez Amazon France

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this exhibition / book / catalogue review have not been put between quotation marks.

Book / catalogue / exhibition review added on November 16, 2023 at 10:45 German time.