Exhibition and catalogue reviews. Biography of the sculptor Alberto Giacometti

The city of Basel currently holds two outstanding exhibitions: one about Van Gogh’s landscapes, the other about Alberto Giacometti. Both are highly recommendable. Here some information about the Giacometti exhibition and catalogue.

Already the exhibitions in Chur and Mannheim in 2000 focused not only on Alberto Giacometti, but on his family too, including his father, the painter Giovanni Giacometti, his distant relative, the painter Augusto Giacometti as well as his brother Diego Giacometti, who made himself a name with his furniture, design objects and sculptures.

However, the catalogue (Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr, Amazon.co.uk) accompanying the exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen near Basel focuses on reproductions of the works by Alberto Giacometti. The book also offers on nine pages thoughts about Giacometti and the exhibition by the curator Ulf Küster , a seven-page essay by Véronique Wiesinger about the relation between father and son, Giovanni and Alberto Giacometti and a seven-page chronology compiled by Michiko Kono. If you would like to learn more about the artist and his life, read the biography by James Lord: Alberto Giacometti (order the English edition from Amazon.de, Amazon.fr, Amazon.com). At the fondation Beyeler, Augusto and Diego Giacometti are only offered a small space at the end of the book; the architect Bruno Giacometti was not included.

The exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler from May 31 to October 11, 2009 displays 150 works of Alberto Giacometti as well as a few works by his father, his brother Diego and his uncle Augusto

Alberto Giacometti’s background – a biography

Alberto Giacometti was born in Stampa on October 10, 1901 the first of Annetta and Giovanni’s four children. Stampa is a village situated in a mountain region called Bergell, located between the Alpine passes of Maloja and Castasegna. Geographically turned towards Italy, it oriented itself towards the north because of the Protestantism of its inhabitants.

Originally from a modest family from central Italy, the Giacomettis were already rich when Alberto was born. His grandfather had married into a wealthy Bergell family. His father followed in the grandfather’s footsteps and married the daughter of the richest family in the valley.

The Giacomettis were a dynamic family. Alberto’s grandfather was a confectioner who emigrated first to Warsaw (Poland) and then to Bergamo (Italy), where he successfully run a coffee-house. He returned to Stampa as a rich man.

Alberto’s father, Giovanni Giacometti, was already a successful neo-Impressionist painter when he was born. In 1908, he exhibited alongside Vincent van Gogh, Cuno Amiet and Hans Emmenegger at Zurich’s Künstlerhaus. Incidentally, Alberto’s godfather was Cuno Amiet, his brother Diego’s godfather was the eminent Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler.

Giovanni Giacometti encouraged his son’s artistic ambitions. Alberto finished his first all drawings in 1913 and his first plasticine sculpture the following year. In 1915, he enrolled in the Evangelic Academy in Schiers. His earliest surviving oil painting, dated 1915, shows that his style was entirely academic as well as his admiration for Cézanne.

In 1919, Alberto left the school in Schiers and moved to Geneva where he first studied at Ecole des beaux-arts and then at Ecole des arts industriels.

After travels to the Venice Biennale and Padua with his father and later alone to Rome and Florence in 1920 and 1921, Alberto, at the suggestion of his father, moved to Paris to study life drawing and sculpture with Antoine Bourdelle at Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Giacometti later wrote about the limits of the academy: “I realized that my vision changed daily. Either I saw a volume or I saw the figure as a blob, or I saw a detail or I saw the whole. given that the models only posed for a very limited period, they left even before I had begun to capture anything at all.”

The young Giacometti suffered from homesickness. He spent a lot of time in 1922 in Stampa and only returned to Paris in autumn to study seriously, encouraged by his father who was wise enough to realize that his son had to remain in the capital of the arts of his time to become a great artist, something Giovanni Giacometti, despite his success, thought not to have achieved. In that period, influenced by Egyptian art, Alberto made numerous plaster sculptures of which only few have survived.

In 1925, Alberto exhibited his works of art for the first time at the Salon des Tuileries. He realized that it was impossible for him to create painting and sculptures exactly the way he saw them and that he had “to abandon the real.” For ten years, he created from memory “on the fringes of truth.”

In 1926, Alberto moved into the studio at no. 46 rue Hippolyte-Maindron in Paris, where he would work the rest of his life. The following year, his interest in Cubism and non-European indigenous art was reflected in his sculpture Femme cuillère. In 1928-29, he had regular exhibitions in Paris and became acquainted with André Breton and the Surrealists, André Masson, Hans Arp, Alexander Calder, Max Ernst, Joan Miró as well as the writers Jacques Prévert and Georges Bataille.

In the catalogue, Michiko Kono also describes what Alberto’s family members did. Let’s just mention that Diego and Alberto started to collaborate more closely together in 1929, with Diego assisting his brother. Diego put his ambitions as a painter on hold to concentrate instead on making armatures and learning the techniques of casting and patination. In tune with Surrealism, Alberto appreciated the unintentional and the imperfect offered by the self-taught Diego, while giving him at the same time precise instructions. Diego later worked for interior designers, including Jean-Michel Frank, for whom his younger sister Ottilia weaved textile items in Switzerland.

Alberto in the meantime followed his interests in Surrealism and was inspired by dreams, the workings of chance, political and sexual objects, as Michiko Kono points out and the works published in the catalogue document.

In 1932 followed Alberto’s first solo exhibition at the Galerie Pierre Colle in Paris, with Pablo Picasso attending the vernissage. The same year, Giacometti participated in the Venice Biennale.

After his father’s death in 1933, Alberto spent most of his time in Switzerland. He returned to Paris in December 1934 and, the following year, broke with the Surrealists. He turned to academic subjects including portraits, nudes, still lives, landscapes and interiors.

Alberto later said that each morning from 1935 to 1940, Diego sat for him as a model. Alberto could only see details but not his brother’s head as a whole. Therefore, he made him go further and further away from him. The result were smaller and smaller sculptures. The more Alberto looked as his models, the less clearly he could see them. He became terrified of the disappearance of things.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City was the first art institution to buy one of Alberto’s works of art (Le palais à 4 heures du matin, a Surrealist work made in 1932, oil and graphite on card, included in the catalogue and part of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti in Paris).

From 1942 to 1945, Alberto could not return to Nazi occupied Paris and stayed in neutral Switzerland. Diego remained alone in Paris and took care of Alberto’s atelier and works. Nothing was destructed or confiscated.

In October 1943, Alberto met his future wife Annette Arm in Geneva. She followed him to Paris in 1946; they married in 1949.

In 1947, in preparation of his exhibition at the gallery of Pierre Matisse in New York, Alberto Giacometti entered a highly productive phase. Annette was his principal female model. He experiments with fragmentation. Jean-Paul Sartre, whom Alberto had met together with Simone Beauvoir in 1941, provides the introduction The search for the absolute to the catalogue of his 1948 exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. It was Alberto’s first solo exhibition since 1934.

According to biographer James Lord, the encounter between Giacometti and Sartre in 1941 and their regular subsequent meetings were fruitful for both artists. Sartre considered Giacometti’s characteristic post-war sculptures – first exhibited in New York in 1948 – an expression of his Existentialism. In New York, Giacometti not only rose to fame, he also met the influential art critic David Sylvester and his later biographer James Lord. The latter later stressed the importance of the Phenomenology, which Alberto had studied in Geneva, for the new fragile sculptures.

As a crucial experience (Schlüsselerlebnis) for his new art, Alberto described a visit to a Paris cinema after the war, when he discerned just undefined black spots instead of a person. When he entered the Boulevard Montparnasse afterwards, his perception of the world, of the depth of space, things, colors and silence had changed. He began to see human heads in void, an emptiness, in the space surrounding them. The heads became immobile. The living seemed dead to him.

In 1949, London’s Tate Gallery purchased his 1947-sculpture L’homme qui pointe (also documented in the catalogue of the Beyeler exhibition). Alberto’s commercial success came with his second New York exhibition in November 1950, where all his large sculptures made in recent years were shown and sold. In addition, paintings and drawings were exhibited and sold too.

Alberto continued his modest lifestyle, whereas his wife Annette wanted to enjoy the fruits of his labor and bought a flat. This was the beginning of their slowly growing discord. He remained an artistic searcher who never found what he was looking for.

In 1951 followed Alberto’s first solo exhibition at the Galerie Maeght in Paris. Francis Ponge devoted an essay to him in the Cahiers de l’art, illustrated with photographs by the Swiss Ernst Scheidegger. Giacometti’s rugged facial features became a favorite motif of many leading photographers, including Robert Doisneau, Arnold Newman, Inge Morath, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Irving Penn.

The subsequent exhibitions are too many to be mentioned here. In 1956, a Japanese friend started to sit for Alberto all day. In the evenings, he painted him. “The better it went, the more he disappeared. on the day he left”, Alberto told him, “If I do another line, the picture will disappear altogether.”

In 1958, Alberto met the 22-year-old Caroline, who would pose for him from 1960 to 1965. From February 1959 to spring 1960, he devoted an entire year to a monumental sculpture outside the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York City. Alberto has casts made of the sculptures for the project. They do not fulfill his expectations and he abandons the project altogether. He does however produce four large female figures, a monumental head and two walking men, which are released as independent sculptures.

In 1963, Alberto underwent a stomach cancer operation in Paris. He continues to work, exhibit, receive awards and accolades. While visiting the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York in 1965, he reportedly said that he would like to take up the monumental project again.

On January 11, 1966 suffering from a chronic bronchitis, Alberto Giacometti died from a heart attack at the Cantonal Hospital in Chur, Switzerland. He was buried at Bogonovo Cemetery where his parents lie too. In 1972, his surviving wife Annette left the rue Hippolyte-Maindron studio at the owner’s request. The building no longer exists. Annette died in 1993 and was buried at the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Her plan to entrust a foundation with her husband’s estate, archives and the material she had collected for the catalogue raisonné came to fruition with the establishment of the Foundation Alberto and Annette Giacometti in 2003.

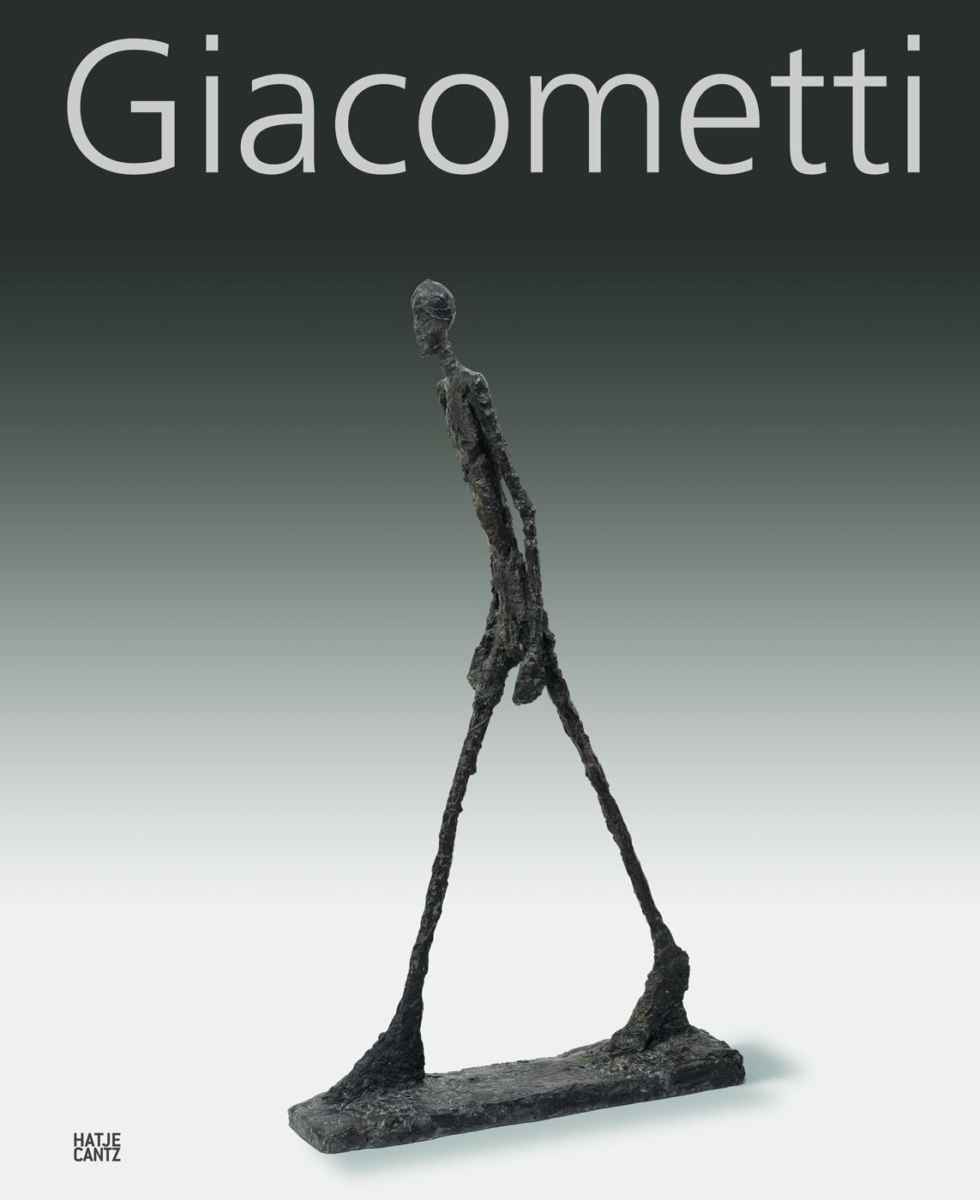

The catalogue with large scale reproductions: Giacometti. Fondation Beyeler, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2009, 224 pages, 194 photos. Order the English catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr, Amazon.co.uk. Die deutsche Ausgabe bestellen bei Amazon.de. Article added on August 2, 2009.

On February 3, 2010 Sotheby’s London sold a 1960-cast in bronze of Alberto Giacometti’s L’homme qui marche for £65 million, making it the world’ most expensive work of art ever sold [added on February 6, 2010].