Until September 10, 2017 Tate Modern in London is presenting the first comprehensive UK retrospective of the sculptor, painter and draughtsman Alberto Giacometti for twenty years (Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr); the only other Tate Gallery retrospective dates back to 1965.

The show came to life in collaboration with Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti in Paris, which holds the world’s largest collection of Giacometti works, comprising some 300 sculptures, 88 paintings and roughly 2,000 drawings as well as archival documents, photographs, decorative objects and more.

The current Tate Modern exhibition presents some 250 works by the Swiss artist. It showcases the evolution of Alberto Giacometti’s career across five decades. The exhibition focuses not only on his body of work, but also on the original and experimental way in which he developed his art as well as the people and the events that influenced him.

Alberto Giacometti was born in the Swiss mountain village Borgonovo in 1901, the eldest son of the protestant, post-Impressionist painter Giovanni Giacometti — for the biography of the artist read our 2009 review of the Giacometti exhibition at Fondation Beyeler.

When Alberto Giacometti moved to Paris in the 1920s, he was influenced by cubism, African and Egyptian art. Subsequently, he became part of the surrealist group around André Breton. It was only when he broke with Surrealism and adopted sculptures in a more realistic style that he began moving towards creating his world-famous, elongated figures.

In December 1941, Alberto Giacometti left Paris for Geneva where, two years later, he met his future wife Annette Arm; they were married in 1949 in Paris. Alberto only returned to the French capital after the war.

Alberto Giacometti made his elongated figures with plaster. They were then covered in orange shellac and cast in bronze. Many of the original plaster sculptures were broken apart or otherwise damaged.

At the Venice Biennale in 1956, the Swiss artist showed female plaster sculptures, the fifteen famous Women of Venice (Femmes de Venise). Nine of them have later been cast in bronze; one of them has been auctioned of by Sotheby’s in 2014 (Femme de Venise V from the Estate of Jan Krugier).

Giacometti showed them not in the Swiss, but in the French Venice Biennale pavilion. The Albert and Annette Giacometti Foundation in Paris has been able to restore the fragile plaster Women of Venice with black and brown lines etched on them. Therefore, at Tate Modern until September 10, 2017 for the first time, eight restored Femmes de Venise plaster sculptures can be publicly admired.

In addition, other restored plaster works such as The Nose from 1947, Tall Figure II and Medium Figure III, both from 1948 as well as Women (Leoni) from 1958 are exposed for the first time too. Furthermore, some archival documents, notebooks and sketches for decorative objects have never been publicly shown too.

Alberto Giacometti said that his works were never finished. One reason for this: “I am very interested in art but I am instinctively more interested in truth […] The more I work, the more I see differently.”

Therefore, the use of plaster and clay was essential for him. Frances Morris and Catherine Grenier rightly point out in their Tate Modern catalogue foreword: “The elasticity and malleability of these materials allowed him to work in an inventive way, continuously reworking and experimenting with his sculpture, creating his distinctive highly textured and scratched surfaces.”

Giacometti at Tate Modern is a fantastic exhibition. 2017 is surely one of the greatest years for art lovers ever. And we’re not even half through the year yet. Giacometti at Tate Modern is a show not to miss.

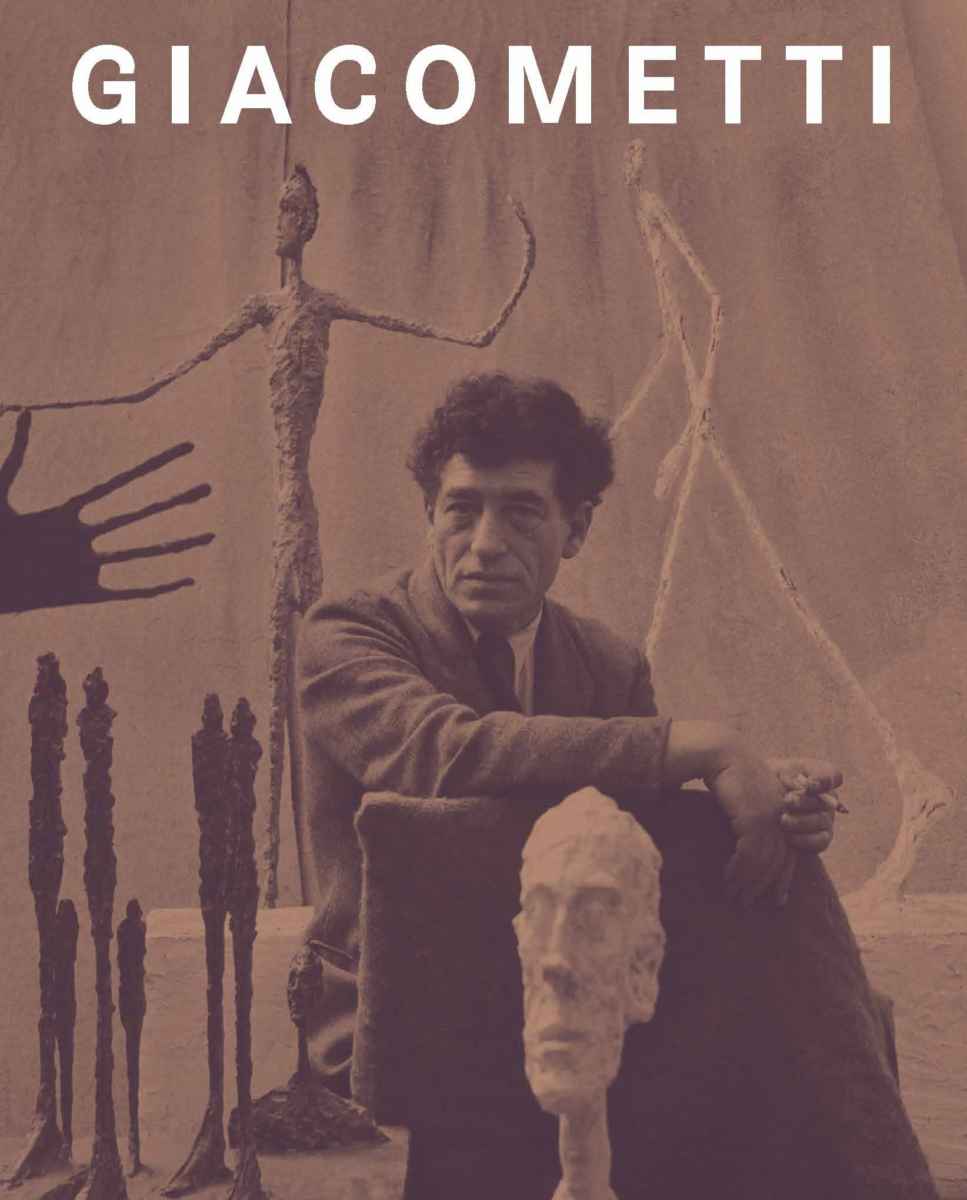

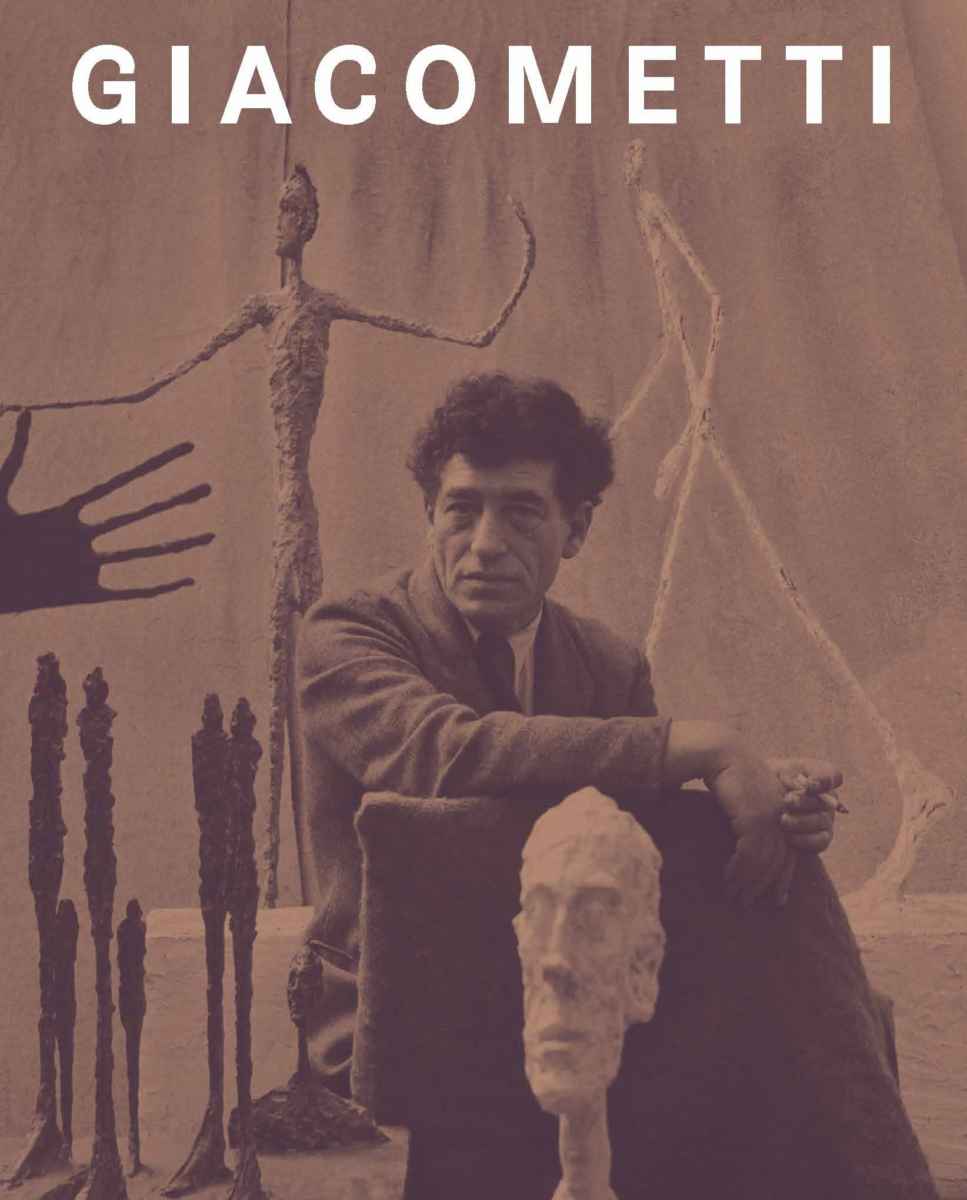

The Tate Modern catalogue: Giacometti. Tate Publishing, May 2017, 256 pages and 220 color illustrations. Order the paperback edition from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr.

The only not so great point about the catalogue is that not only the text, but also the photographs in the informational part of the book are in violet color. Why? The exhibited works of course are all photographed in natural light. No problem there.

Article added on May 20, 2017 at 17:15 Swiss time.