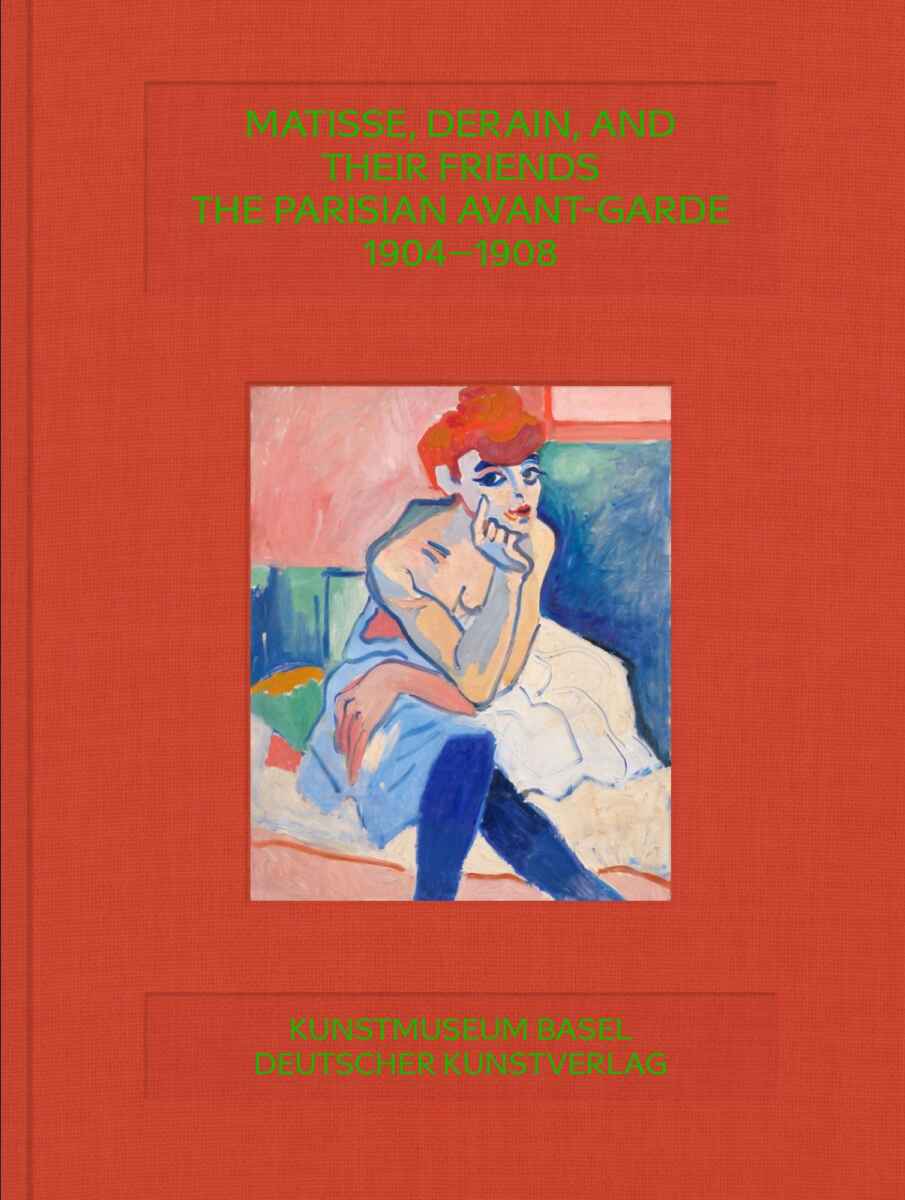

In the year 1661, the government of the city of Basel decided to create the world’s first art museum open to the general public: Kunstmuseum Basel. In the Swiss city, on September 1, 2023 the vernissage of the exhibition Matisse, Derain and their Friends: The Parisian Avant-Garde 1904-1908 took place. The catalogue editors Arthur Fink, Claudine Grammont and Josef Helfenstein presented their concept and pointed out some highlights of their show, which presents over 160 paintings, sculptures and ceramics by the Fauves and will last until January 21, 2024.

This article is partly based on their explanations and mostly on the detailed, very recommendable English Kunstmuseum Basel exhibition catalogue with contributions by six authors: Arthur Fink, Claudine Grammont, Gabrielle Houbre, Peter Kropmanns, Maureen Murphy and Pascal Rousseau (English version: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr).

The first 20th century avant-garde movement — later known as Fauvism — only lasted from 1904 until 1908. The term Fauves (wildcats, wild beasts or wild animals) was coined by the French art critic Louis Vauxcelles, based on disparaging comments by conservative critics of the revolutionary art shown by some artists at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1905.

According to anecdotal accounts, at the opening of the exhibition, Louis Vauxcelles himself exclaimed: “Look, Donatello in the midst of wildcats!” (“Tiens, Donatello au milieu des fauves!”). The analogy caused so much laughter that he used it again in his review. In the same room as the paintings by the Fauves, a traditional sculpture by Albert Marque, influenced by the Italian High Renaissance, was shown. This sculpture, wrote the critic, appeared as if it had landed in the midst of an “orgy of pure color”— a “Donatello chez les Fauves”.

The artists involved in Fauvism wanted to liberate painting from a highly codified set of academic rules. They advocated for a simplification of technical means through a radical departure from painterly conventions.

They were not the first to do so. Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) and Paul Cezanne (1839-1906; no spelling error! The findings of recent research show that Cezanne comes without an acute accent or accent aigu on the first e) were three of several artistic predecessors of the Fauves.

In fact, the first meeting of Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain and Henri Matisse took place in 1901 at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery at a Van Gogh retrospective. The fact that Van Gogh was not educated in the French academy system made him a particularly attractive role model.

The Basel catalogue authors stress that the Fauvism was not a uniform mouvement. Three ideologically diverse artistic milieus articulated similar painterly strategies. One group consisted of graduates from the class of the Symbolist Gustave Moreau at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the private Académie Carrière (Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Albert Marquet (1875-1947), Henri Charles Manguin (1874-1949), Charles Camoin (1879-1965), and Jean Puy (1876-1960). Another group was made up of the Paris-born Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) and André Derain (1880-1954), who painted together in the Paris suburb of Chatou, where Derain was born. Around 1905, they were joined by young painters from Le Havre: Raoul Dufy (1877-1953), Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Othon Friesz (1979-1949), who viewed the older Matisse as a model.

Especially Matisse was severely criticized for his anti-militarism. Because of the positive reception of the movement in Germany and Russia, Fauvism soon came to be considered an art boche or art bolshevik, in contrast to Cubism.

In his catalogue essay, Josef Helfenstein writes that, by the end of 1907, the loose artist association was already fraying. Braque and Derain were drawn to the Bateau-Lavoir, where Pablo Picasso had his studio, and were they embarked on a new adventure called Cubism, another term coined by a salon review by Louis Vauxcelles.

Back to the Fauves: the irony is of course that some of them came from the Académie des Beaux-Arts and turned against it and its stiff academism. Josef Helfenstein writes that, although they sometimes broke with social conventions, they had a strong sense of tradition. Their view of African and Asian art was thoroughly Eurocentric. Although some of their statements and caricatures were critical of colonialism, overall the painters remained bound by the racist and chauvinist as well as by the traditional gender thinking of their time.

The Fauves were a loose association of artists with no clear aesthetic agenda expressed in any kind of programmatic writings or manifestos. Fauvism was part of a larger colorist mouvement in Europe around 1900. In addition, a central theme of the time was the representation of the figure. The Fauves eagerly sought new pictorial ways to represent the human body. Therefore, the first of the nine rooms at the Kunstmuseum Basel exhibition begins with a group of early nude studies and ends with a group of woodcuts by Derain and Matisse.

The catalogue explores the role of art critics and the art market in the creation of the Fauvism art movement and the launch of the careers of the Fauves. Group and solo exhibitions arranged by the Parisian gallerists Berthe Weill, Ambroise Vollard, Eugène Druet, Eugène Blot, Gaston and Josse Bernheim-Jeune as well as by the bookstore Librairie Prath et Maynier are analyzed.

The virile connotation of the term Fauves suggests the exclusion of female artists at a conceptual level. The Basel exhibition and catalogue challenge this view and make visible several women who played a key but almost unknown role in Fauvism. The art dealer Berthe Weill was the first to substantially promote the Fauves. She was the only female gallerist in Paris around 1900. Shortly after the Salon scandal of October 1905, she organized an important Fauvism exhibition at her gallery. She was also one of the few art dealers to include women artists in her roster and to promote them, notably Emilie Charmy and Marie Laurencin, both represented with works in Basel.

During the short existence of Fauvism, Marie Laurencin was known as “the doe among the wild beasts” (la bicheparmi les fauves) or la fauvette. As a fellow student of Georges Braque and partner of Guillaume Apollinaire, Marie Laurencin was part of the avant-garde circle, but her role was minimized by the male fraternity. The same was true of Wmilie Charmy, whose work still remains to be discovered. She painted side by side with her then partner Charles Camoin and produced radical self-portraits.

At the exhibition Matisse, Derain and their Friends: The Parisian Avant-Garde 1904-1908, you can admire Marie Laurencin’s portrait of Alice Derain, the wife of André Derain, as well as a (self-) portrait of her alter ego, the hunting goddess Diana. Another important female Fauve who has barely been recognized as such is Amélie Parayre-Matisse, whose textile designs provided the economic foundation for her husband’s art. In her catalogue essay, the co-curator of the exhibition, Claudine Grammont, examines the fashion discourses of the turn of the century and discusses the significant role of Amélie Parayre-Matisse within the Fauve circle.

The Parisian historian Gabrielle Houbre not only contributes historical sources to the exhibition but, in her catalogue essay, she reveals the social reality of sex workers who served as models for the Fauves. She notably discovered that the singer Modjesko is not a female soprano. In 1908, the Fauve painter Kees van Dongen made a portrait (exhibited in the Basel show) of the drag queen Modjesko, who has often and falsely been described as a soprano of Romanian origin.

In reality, Gabrielle Houbre identified Claude Modjesko as a man born into a poor family in Beaufort, South Carolina in 1877 or 1878. After starting out in minstrel shows at the age of fifteen, he began a career as a drag singer in Europe in 1898. He supplemented his meagre earnings by prostituting himself and fleecing some of his more famous clients. In 1905, he appeared in Paris under the stage name “the Black Patti” or “the Creole Patti,” exposing herself as a drag queen to both the racist and heteronormative prejudices of the time. During Modjesko’s first appearances at the Paris Olympia, he was overshadowed by the star of the program, the dancer (and notorious spy) Mata Hari. Both the audience and the press were fascinated by Mata Hari and her sophisticated play on nudity and exoticism. Modjesko’s act only got a few brief mentions, sometimes as a man (“Avirtuoso Negro [man]”, in La Petite Presse, August 21, 1905), sometimes as a woman (“Modjesko, a Black [female] singer”, in Le Gaulois, August 20, 1905), but always, as was common practice when talking of Black artists at that time, with reference to the color of his, or her, skin.

According to Gabrielle Houbre, both Kees Van Dongen and Ludovic Pissarro heard Modjesko at the Circus Variété in Rotterdam in July 1907. Both artists painted the drag singer performing. Kees Van Dongen made several studies for his 1908 painting in his native city of Rotterdam. He refrained from the caricatural effect of Ludovic Pissarro’s painting. It is not known whether the two artists were aware of Modjesko’s wild and outrageous life. In late 1907, he was arrested in New York City together with the French tenor Léon Cazauran for suspicious behavior with twelve to thirteen-year-old boys. He got off with a ten-dollar fine for an “obscene” photograph found in one of his pockets.

These are just a few details about a notable exhibition at Kunstmuseum Basel, which includes many highlights, including Henri Matisse’s Nu aux souliers roses (1900), which has been described as a colorist breakthrough. The catalogue offers new insights into the life and work of the Fauves as well as their historical context.

The catalogue edited by Arthur Fink, Claudine Grammont and Josef Helfenstein: Matisse, Derain and their Friends: The Parisian Avant-Garde 1904-1908. Deutscher Kunstverlag, September 2023, 266 pages. Order the English book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr.

The German edition: Matisse, Derain und ihre Freunde, Deutscher Kunstverlag, September 2023, 352 pages. Order the German version of the catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this exhibition and catalogue review of Matisse, Derain and their Friends: The Parisian Avant-Garde 1904-1908 have not been put between quotation marks.

Exhibition / book / catalogue review added on September 4, 2023 at 12:50 Swiss time.