Together with Mercedes-Benz, Ferrari is probably the most famous name in the world of cars. In a new, lavishly illustrated TASCHEN book, the writer and journalist Pino Allievi explains that, after the Second World War, Italian entrepreneurs such as Enrico Piaggio, Ferdinando Innocenti, Giorgio Parodi, Carlo Guzzi, Giovanni Agnelli, Alberto and Piero Pirelli soon came to symbolize the drive for a fresh start. However, as their low-cost creative euphoria took hold, down in the city of Modena, one man was very quietly going in completely the opposite direction: Enzo Ferrari (1898-1988). He hovered between scorn and recklessness, designing a revolutionary and hugely expensive 12-cylinder car to launch first on the track and then later to win the hearts of both new money and people that had somehow escaped the financial collapse of the war.

Pino Allievi: Ferrari. TASCHEN, October 2025, 688 richly illustrated pages, 5 kg, 28 x 6.6 x 37.4 cm. ISBN-13: 978-3754401354. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Based on unrivalled access to photos and documents from the Ferrari Archives and private collectors, Pino Allievi tells the story of Enzo Ferrari and his cars. The book contains forewords by Enzo Ferrari’s son Piero and Gianni Agnelli’s grandson John Elkann, who is the CEO of Excor, the holding company which controls, among other companies, the automaker Ferrari.

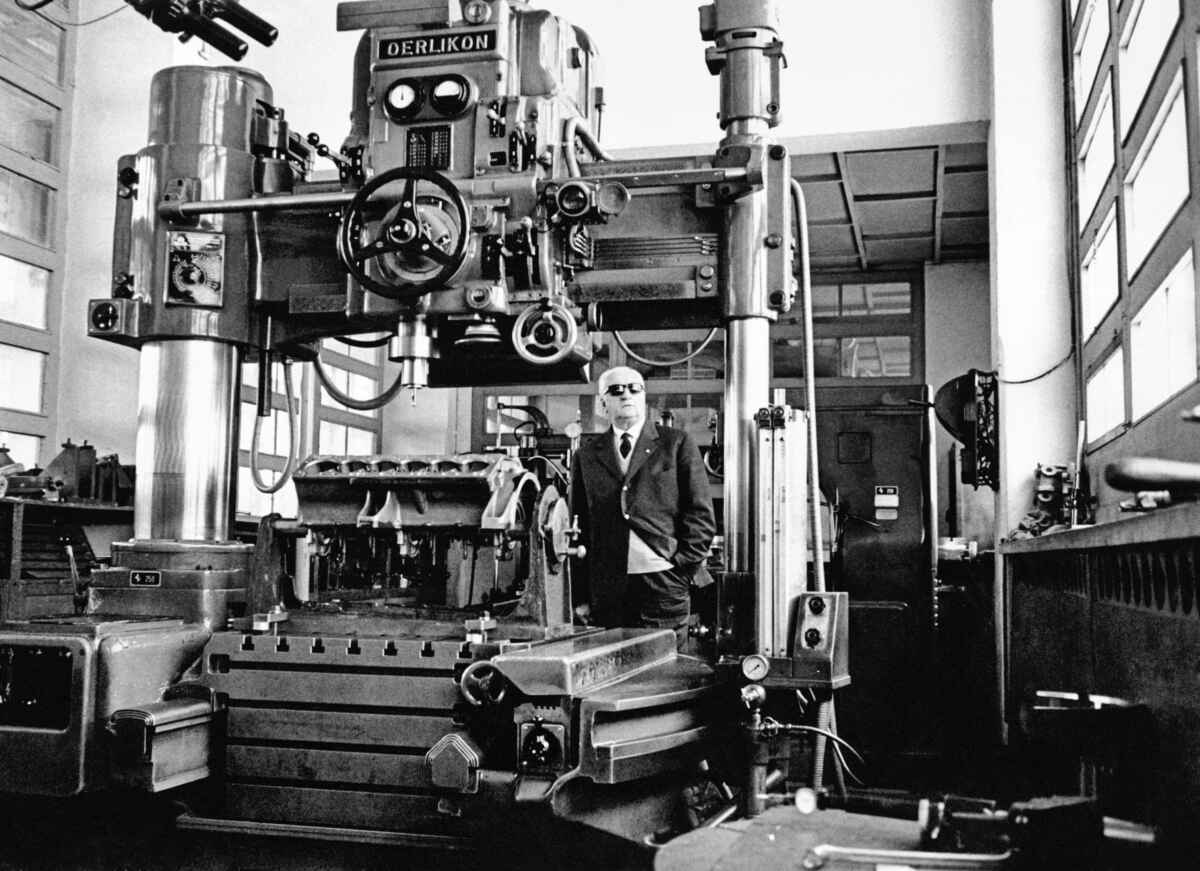

An imposing-looking Enzo Ferrari watches work being done on a 12- cylinder engine. Photo copyright © MONDADORI PORTFOLIO, via Getty Images. Page 436 of Pino Allievi’s richly illustrated Ferrari book. The Swiss may recognize that Ferrari used a Swiss precision machine, as indicated by the “Oerlikon” sign.

The young Enzo aspired to become an opera singer, sports journalist, or race car driver. He quickly realized that he lacked the necessary musical talent, but on November 16, 1914 his report on the Modena-Inter soccer match was published in La Gazzetta dello Sport.

However, when his father, who owned a mechanical workshop, which worked for the nearby railways in Modena, bought his first car, a single-cylinder De Dion Bouton, which was later replaced by a two-cylinder Marchand and finally by a four-cylinder Diatto Torpedo, Enzo’s love for cars became dominant.

It was in in his father’s cars that the young man learned to drive. Unfortunately, in 1915, Enzo’s father died of pneumonia. The following year, his older brother, who had volunteered at the outbreak of the Great War, died from pleurisy. While waiting to be called up for military service, thanks to his knowledge of machine tools, 18-year-old Enzo found employment as an instructor at the Modena Fire Department Workshop, where courses were held to train workers for use in auxiliary industries.

According to the detailed Italian Wikipedia entry, in 1917, Enzo was enlisted in the Italian army and assigned to the 3rd Alpine Artillery Regiment, but was discharged the same year due to pleurisy. After a brief pilgrimage among the many metalworking companies in Turin, Enzo found employment at Carrozzeria Giovannoni, which specialized in the recovery of automobiles and light trucks that had been decommissioned from military use. Once the bodies had been demolished, the chassis were reconditioned and delivered to Carrozzeria Italo-Argentina in Milan, which converted them into luxury torpedo or coupé de ville cars.

In addition to his workshop duties, the young Ferrari’s job was to test the reconditioned chassis and deliver them to the customer in the Lombard capital. He thus became an expert driver. However, demand for reconditioned chassis waned within a few months as car manufacturers gradually converted back to civilian production, leaving Ferrari unemployed once again.

Both are red, stunning, and feature a 5 L V12 engine, but they are very different from each other: the 410 S coupé version (left) and spider (right); 1955. Photography copyright © Rainer W. Schlegelmilch/Motorsport Images. Pages 88/89 of Pino Allievi’s richly illustrated Ferrari book.

In his book, Pino Allievi mentions that Enzo Ferrari had started his career at Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali (CMN), a car manufacturer based in Milan. Quickly, Alfa Romeo spotted his potential and hired him. Subsequently, Ferrari succeeded in luring some of the best engineers away from the then dominant Fiat car company to Alfa Romeo, hailing the demise of the Turin manufacturer’s racing ambitions and ushering in a slew of triumphs for the Milanese team.

Pino Allievi does not mention that, in 1924, Enzo Ferrari Ferrari participated in the founding of the Bologna sports newspaper Corriere dello Sport, remaining managing director of the publishing company until 1926, when he withdrew from publishing.

According to Pino Allievi, despite ambitions to become one, Ferrari was never a professional driver. When he had the chance to drive for the official Alfa Romeo works team in the 1924 French Grand Prix in Lyon, Enzo Ferrari returned home the day before the race, claiming he was having a nervous breakdown. Nevertheless, in a few lines with editing errors, Allievi writes that Enzo won 15 of the 39 races in which he competed between 1919 and 1931.

Between 1929 and 1937, Enzo ran the Scuderia Ferrari, a private team—as it would be called today—that fielded nearly only Alfa Romeo cars. Gentlemen drivers could hire—at a price—highly competitive cars to race where they wanted with the highly efficient Scuderia Ferrari providing support.

When the Scuderia was founded, Ferrari held onto 25% of the company’s stock, leaving a majority stake to wealthy brothers Augusto and Alfredo Caniato (the latter was the first chairman until 1932). Alfa Romeo and Pirelli also bought stakes, a move that lent extra prestige to the operation.

Allievi underlines that Ferrari hired talented professional drivers, including Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari. The Scuderia clocked up a long string of prestigious victories, including the Mille Miglia, Targa Florio, and open-wheel Grand Prix wins. That exhilarating adventure lasted eight years, with 656 cars fielded in 224 races, winning a total of 122 victories.

Returning to Ferrari’s beginnings at Alfa Romeo: Enzo alternated racing the marque’s cars and acting as a consultant to the head of sales, Giorgio Rimini, an engineer who sensed in the young man from Modena a great entrepreneur. At the age of 22, Enzo set up a small coachbuilder company in Modena. However, he had little time to devote to the business. Therefore, it struggled on for a few years before eventually folding. He had to get help from his mother to pay off its debts.

Allievi highlights that racing was dangerous. Not only many of Ferrari’s colleagues and rivals, but also close friends died: Biagio Nazzaro at Strasbourg (1922), Ugo Sivocci at Monza (1923), Antonio Ascari at Montlhéry (1925), and Giulio Masetti in the Targa Florio (1926).

In the meantime, Ferrari was building up experience and improving his driving technique. This led him to clock up several wins. Eventually, he was given an official Alfa Romeo for the European Grand Prix at Lyon. Ferrari was now just one step away from the top of the game. But it was a step he did not want to take. Allivei writes, as mentioed above, that Enzo went home, in the grips of nervous exhaustion, as depression was referred to in those days, and wisely decided to look after his health. He continued to race—and even win—every now and then, but stayed well clear of Grand Prix driving, throwing his energy instead into building his career as an entrepreneur.

Torrential rain at the start of the 1968 Le Mans 24 Hours, when the Ferrari 275 LM of Masten Gregory– Charlie Kolb sprints ahead, followed by the Ford GT40 of Jackie Oliver–Brian Muir and the Alpine 220 of Henri Grandsire– Gérard Larrousse. Photo copyright © Rainer W. Schlegelmilch/Motorsport Images. Page 404/405 of Pino Allievi’s richly illustrated Ferrari book.

Ferrari had not even turned 32 when he founded the Scuderia bearing his name. Among the famous drivers racing for the Scuderia Ferrari were Giuseppe Campari, Luigi Arcangeli, Baconin Borzacchini, Tonino Brivio, Luigi Fagioli, Felice Trossi, Piero Taruffi, Louis Chiron, Guy Moll, Giuseppe Farina, Clemente Biondetti, Raymond Sommer, Achille Varzi, Tazio Nuvolari, and others. Unfortunately, the Scuderia’s huge racing success and popularity was marred in part by terrible accidents that ended the lives of high-caliber champions of the likes of Luigi Arcangeli (Monza, 1931), Giuseppe Campari and Baconin Borzacchini (who died together at Monza in 1933), and Guy Moll (Pescara, 1934).

Allievi mentions a counterpoint to those tragic fatalities: a series of triumphs for the Scuderia in the mid-1930s. Firstly, the red Alfa Romeos bearing the legendary Prancing Horse (which had adorned the cars since 1932) won three of the classic endurance races (Mille Miglia, Targa Florio, 24 Hours of Spa) again and again. In addition, the Scuderia won in the Italian (Monza), French (Montlhéry), Czechoslovakian (Brno-Masaryk-ring), Spanish (San Sebastián), AVUS (Berlin), Monaco (Monte Carlo), and Hungarian (Budapest) Grand Prix, as well as a succession of triumphs in internationally renowned races in Europe, Africa, and America, including Barcelona, Tripoli, Tunis, Casablanca, Rio de Janeiro and, most sensationally, the Vanderbilt Cup in New York. Mussolini‘s Fascist regime leapt on the bandwagon for its own propaganda purposes: the little Italian David defeating the giant Goliath on the other side of the Atlantic, very fittingly on October 12, Columbus Day, the anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s landing in America.

Unfortunately, Ferrari and Nuvolari had had a major falling-out as the latter wanted more of a say in technical matters and on the set-up of the cars he drove. He also demanded that the Scuderia’s name be changed to Nuvolari-Ferrari. According to Allievi, happily, the disagreement did not end up in the courts, but the two men went their separate ways for a year and a half, which gave both of them time to reflect. Ferrari could see that Nuvolari was as capable of winning in a Maserati as in one of his cars, while Nuvolari realized that managing a racing season on his own reduced his income more than he had anticipated. The duo thus reached a compromise, and the Prancing Horse, with Nuvolari in the saddle, was soon back racing faster than ever.

In the meantime, the balance of power between the rival racing marques was shifting fast with the German Mercedes and Auto Union teams pulling out all the stops to dominate the scene. But prior to 1936 those ambitions were derailed on several occasions by Tazio Nuvolari.

When Europe slid into the abyss of World War II and Alfa Romeo decided to take the management of its racing division in-house, Scuderia Ferrari was put into liquidation. Concurrently, however, Alfa Corse was created and Enzo Ferrari was appointed as its head. Allievi underlines that, from a financial point of view, this was an advantageous arrangement, but Ferrari found losing his decision-making powers and having to report to general manager Ugo Gobbato intolerable. The contract was terminated in September 1939. Ferrari returned to Modena, after agreeing not to engage in any “technical-competitive activity” for four years.

However, back in Modena, Enzo Ferrari immediately set up a new company: Auto Avio Costruzioni. He got to work on two prototypes of a new two-seater that he called the 815, as he was prohibited from using his own name. The car had its maiden race in a version of the Mille Miglia that took place on a shorter course in 1940, but failed to shine. Soon after that event motorsport in general would be forgotten as Italy was plunged into war. Ferrari’s fortunes continued to fluctuate dramatically. At the end of 1942 he purchased some land in Maranello and built a small factory to which he moved the machine tooling company he had been running in Modena.

Between 1943 and 1946, with the settlement he had received when he had quit Alfa Romeo at the end of 1939 after heading its racing division for two years, Enzo Ferrari was producing sophisticated hydraulic grinding machines for making ball bearings at his Auto Avio Costruzioni company.

Pino Allievi writes that the Germans occupied the factory in September 1943. They suspected that the grinding machines, which were of the finest quality, were copies of German technology and so ordered them to be sent to Germany for the war effort there. This was also why the Allies bombed the factory in November 1944 and February 1945. After the war, the workers returned and got the factory back into working order.

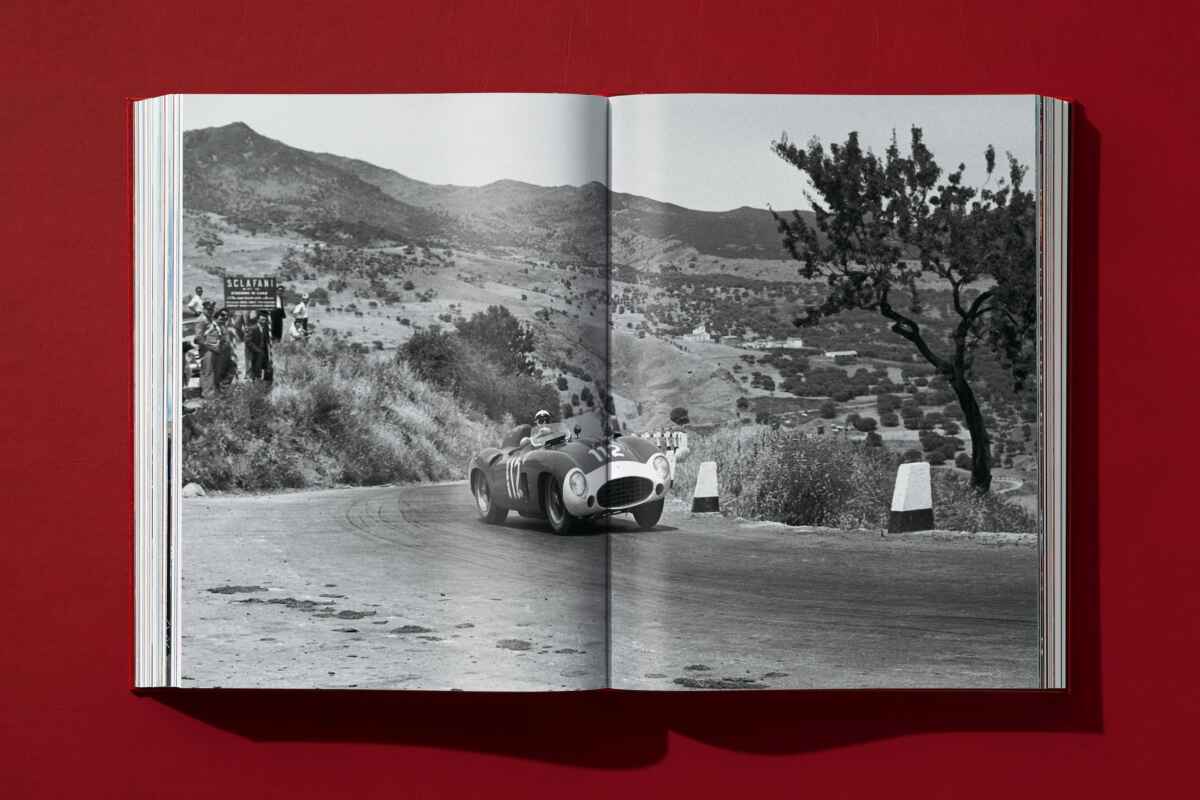

The spectacular background of the Targa Florio: it is 1956, and the Ferrari 860 Monza of Eugenio Castellotti–Peter Collins faces a fast uphill curve in the municipality of Sclafani. Photo copyright © The Cahier Archive. Pages 378/379 of Pino Allievi’s Ferrari book.

Until 1946 Ferrari made machine tools. But he never lost his racing ambition. Already in 1940, he secretly broke his agreement with Alfa Romeo not to build racing cars for four years and unveiled the stunning 815 to the press under the new Auto Avio Costruzioni name. The racing version of the 1,500 cc 8-cylinder was immediately snapped up by Marquis Lotario Rangoni Machiavelli and a young Alberto Ascari, who put it into action at the Grand Prix of Brescia-Trofeo Mille Miglia in 1940. Ascari would eventually go on to win the 1952 and 1953 Formula 1 World Championships in a Ferrari.

Back to the immediate aftermath of war: Gioachino Colombo set about designing the 12-cylinder engine for the 125 S, which is considered the first real Ferrari and which made its first public appearance at the Circuito di Piacenza on March 12, 1947, taking its first victory on May 25 at Rome’s Circuito di Caracalla with Franco Cortese at the wheel.

In 1939, Enzo had declared: “I left Alfa Romeo to prove to them who I was.” He officially set up Ferrari as his own company in 1947. In 1951, Ferrari managed to beat Alfa Romeo at the British Grand Prix in Silverstone. Until that day, Alfa Romeo had dominated the scene, ironically enough winning the 1950 world title with the Alfa Romeo 158, the very car Enzo had designed and built in Modena. Ferrari said after the Silverstone victory: “It felt like I had killed my mother.” According to Allievi, Ferrari used this laconic yet dramatic words, knowing full well the impact and resonance a few well-chosen words could have.

In the following chapters, Pino Allievi presents the epic story of the Prancing Horse (Cavallino rampante) on the Ferrari hoods, Enzo’s DNA to fight alone against the world, great champions, the dangers of racing, legendary races, technology and innovation, the talent factory, the famous people who met in Maranella, the legacy of Enzo and the future of Ferrari after the death of the company founder.

In addition, the book offers a list of all Ferrari victories, international titles as well as stylized side views of all Ferrari models ever produced, including some information. For instance about the first car you can read: “1940 – Auto Avio Costruzioni 815. 1,496 cc, in-line 8-cylinder, 72 hp, 625 kg. This is the forebear of all Ferraris, although it never bore the Prancing Horse badge because when he left Alfa Romeo Enzo Ferrari agreed not to use his own name on any of his designs until 1943. The 815 was powered by two end-to-end Fiat 4-cylinder engines. Number built: 2.”

The Ferrari 158 of John Surtees appears to be floating on water at the British Grand Prix of 1963, where the English driver came second, preceded by Jim Clark with the Lotus-Climax. Photograph copyright © Jesse Alexander, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles. Pages 230/231 of Pino Allievi’s richly illustrated Ferrari book.

During his career, Ferrari worked with many designers, including Scaglietti, Touring, Vignale, Pininfarina, Ghia, Boano, Ellena, Allemano, Frua, Bertone, Zagato, Autodromo, and many others. Regarding Ferrari and Battista “Pinin” Farina (1893-1966), who changed his last name to Pininfarina in 1961, Allievi writes that the two self-made men were on the same wavelength. Enzo Ferrari himself said: “I have always love Pininfarino for what he was able to create. He launched a style, a line, he was the first true ‘tailor’ of the autombile world, the one who was able to bring to light its element of haute couture.”

Pininfarino for instance designed the 456, the 550 Maranello, the 360 Modena, the F430 and the Enzo. As for Sergio Scaglietti (1920-2011), among his designs were the Mondial, the 250 Testa Rossa, the Monza and the 250 GTO for Ferrari.

At the end just one anecdote: Enzo Ferrari showed many famous people around his Maranello factory. The Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in 1952 and 1956, who was defeated on both occasions by Dwight Eisenhower, Adlai Stevenson was surely not the most glamorous people he met. At the end of the visit, Ferrari himself offered to accompany Adlai Stevenson and his wife as far as to the motorway. At one point, Stevenson turned to Enzo’s assistant and asked him to send his regards to Mr. Ferrari. He had never realized that the man showing him around was Mr. Ferrari. They all had a good laugh about the misunderstanding. The Ferrari name may have been famous in the United States, but only few knew how the man behind the iconic cars looked like.

This and much more, last, but not least, plenty of photographs, including some by celebrities such as Miles Davis, Paul Newman, William Holden, Jane Mansfield, Alain Delon and Shirley MacLaine, who liked to pose with their Ferraris, can be discovered in the book by Pino Allievi: Ferrari. TASCHEN, October 2025, 688 richly illustrated pages, 5 kg, 28 x 6.6 x 37.4 cm. ISBN-13: 978-3754401354. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this review of Pino Allievi’s book Ferrari are not put between quotation marks.

Book review of Pino Allievi’s Ferrari added on November 17, 2025 at 20:24 Italian time.