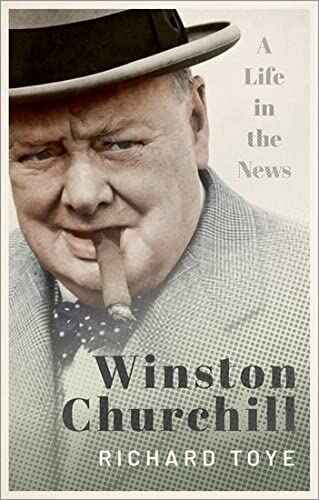

Richard Toye, Professor of Modern History at the University of Exeter, writes in his book Winston Churchill — A Life in the News (Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de) that Churchill first made his name via writing and journalism, he himself was a news-obsessive throughout his life, his own efforts made him a hero, but it was the media that made him a celebrity.

Richard Toye underlines that, in the era of Trump, authoritarian populism, and social media, cries of ‘Fake news!’ are ubiquitous. Whereas Churchill did, until the end of his career, periodically praise the press as a healthy factor in politics because it drew attention to governments’ shortcomings, his attack on the Daily Herald mentioned at the beginning of Toye’s study was no one-off lapse. As an instinctive showman, and one of the first politicians to be a true global celebrity, Churchill exploited the media (including the new technologies of radio and film) to spectacular effect. But—except when an off-the-record indiscretion happened to suit his purposes—his first instinct was for concealment, by no means always on legitimate national security grounds. As someone who did not merely read newspapers but rather devoured them, he was often nettled by criticism to the point where, during World War II, he wanted to censor opinion and not merely sensitive facts.

Richard Toye stresses in his book that Churchill was a master of publicity who cultivated a new form of political celebrity. There were precursors: Palmerston, Gladstone, and Disraeli had all had their personal cults. What was new was the sheer scale of Churchill’s coverage and its transmission across the world. Churchill’s longevity as an object of public discussion (including posthumously) is one of the things that make him special if not absolutely unique, all according to Toye.

Regarding Winston Churchill’s (rare) achievements, the author mentions that he introduced Labour Exchanges, the purpose of which was to help the unemployed find work and that, also throughout his tenure at the Board of Trade, Churchill worked closely with Lloyd George at the Treasury to create a state system of National Insurance against unemployment and ill-health. Richard Toye does however not explain how the press received these major reforms, which make Churchill stand out until today.

Richard Toye writes that one of the bright young men whom Churchill recruited to help him fulfil his social reform agenda was William Beveridge, an Oxford graduate who had dedicated himself to the cause of social reform. He had been employed as a leader-writer for the Morning Post, and had been given a free hand to express his progressive views, even though the paper’s general line was Conservative. Under the editorship of Fabian Ware—Churchill’s friend Oliver Borthwick having died in 1905—it ‘threw itself wholeheartedly into the campaign of the National Anti-Sweating League’. In 1908, however, the paper passed under the control of Lady Bathurst, who was much more partisan in her opinions, and within a few years the Morning Post would become a relentlessly anti-Churchill organ. Churchill succeeded in getting some decent coverage for his handling of the Board of Trade by careful briefing of what he called the ‘Keynote’ press. In public, though, he continued to insist that the Liberal Party faced ‘a hostile press’, which was ‘ranged against it.’ Richard Toye underlines that, actually, the picture was more complicated than that comment suggested. The press was deeply divided and both the main parties reached out their tentacles in efforts to control, influence, and manipulate it; the Tories were particularly adept at providing covert subsidies to favoured papers.

Richard Toye highlights that Churchill retained his status as a darling of the press, even while many papers continued to hammer him for his political conduct and views. Today, Churchill is associated with cigars, yet at this stage in his career, the ‘trademark’ which cartoonists started to use to identify him was a very small hat. According to Churchill, ‘the legend of my hats’ dated from an occasion around this time when he went for a walk with Clementine on the sands at Southport, and unthinkingly put on ‘a very tiny felt hat’ that had been packed with his luggage. Winston Churchill complained: ‘As we came back from our walk, there was the photographer, and he took a picture. Ever since, the cartoonists and paragraphists have dwelt on my hats; how many there are; how strange and queer; and how I am always changing them, and what importance I attach to them, and so on. It is all rubbish, and it is all founded upon a single photograph.’

Regarding one one of Churchill’s many blunders, Gallipoli, Richard Toye writes that Churchill button holed any journalist who would listen, on one occasion staying up till 2 a.m. to try to prove to an unconvinced Charles Repington that he had been right about Antwerp and the Dardanelles. Churchill showed confidential documents about these and other episodes to C. P. Scott, and even offered to let him take them away to study, before having second thoughts. According to Toye, Gallipoli was to be successfully evacuated at the end of the year, but before that occurred Churchill became increasingly frustrated at being sidelined from the central direction of the war. In November, having been excluded from the membership of the newly-formed War Council, he decided to resign from the Cabinet and take up a military command in France. He made a valedictory speech in the Commons that was generally seen as dignified, or at least ‘clever’, if not absolutely convincing on all points. In a sympathetic editorial, the Daily Mail described it as ‘very fine’. Such comments brought down the wrath of Northcliffe upon editor Thomas Marlowe: ‘I wish you would not start “booming” Churchill again. Why do you do it? We got rid of him with difficulty, and he is trying to come back. “Puffing” will bring him back.’

The story of Churchill and the news is a tale of tight deadlines, off-the-record briefings and smoke-filled newsrooms, of wartime summits that were turned into stage-managed global media events, and of often tense interactions with journalists and powerful press proprietors, such as Lords Northcliffe, Rothermere and Beaverbrook. Uncovering the symbiotic relationship between Churchill’s political life and his media life, and the ways in which these were connected to his personal life, Richard Toye asks if there was a ‘public Churchill’ whose image was at odds with the behind-the-scenes reality, or whether, in fact, his private and public selves became seamlessly blended as he adjusted to living in the constant glare of the media spotlight.

Winston Churchill — A Life in the News is also the story of a rapidly evolving media and news culture in the first half of the twentieth century, and of what the contemporary reporting of Churchill’s life (including by himself) can tell us about the development of this culture, over a period spanning from the Victorian era through to the space age.

These are just a few take-aways from an insightful book about one of Britain’s most important, controversial and complexe politicians and his relation with and coverage by the press.

Richard Toye: Winston Churchill — A Life in the News. Hardback, OUP, August 2020, pages, 378 pages. Order the Oxford University Press paperback edition, November 2021, from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review are not (always) put between quotation marks.

Book review added on January 10, 2022 at 16:53 Swiss time.