From October 30, 2024 until February 16, 2026 the Leopold Museum in Austria’s capital Vienna shows the exhibition Rudolf Wacker. Magic and Abysses of Reality. Together with Franz Sedlacek, Rudolf Wacker is considered the most important representative of New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) in Austria.

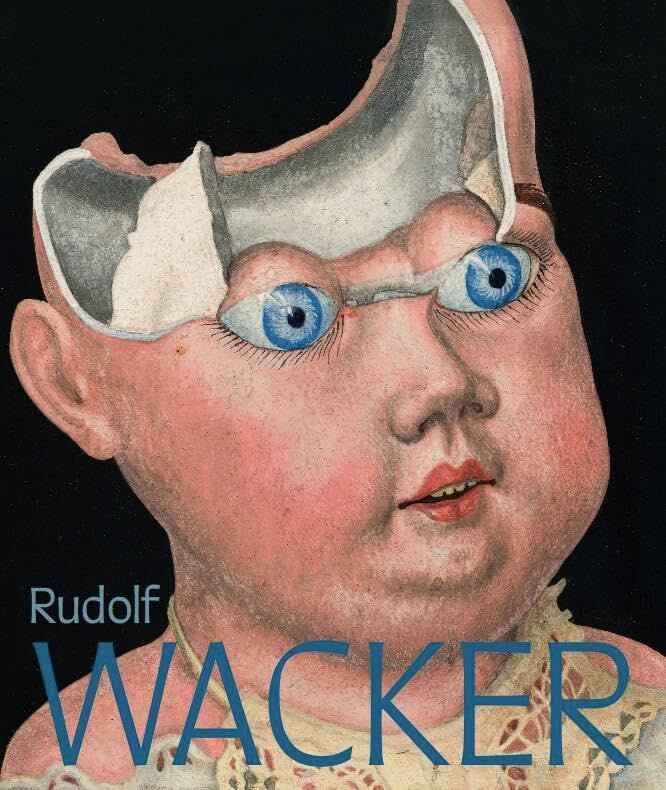

The homonymous catalog: Marianne Hussl-Hörmann, Laura Feurle & Hans-Peter Wipplinger, editors.: Rudolf Wacker. Magic and Abysses of Reality, Leopold Museum, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2024, 23,5 x 28 cm, 336 pages with 260 color illustrations, hardcover, bilingual text in German and English. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the bilingual (English and German) exhibition catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de.

The comprehensive Rudolf Wacker (1893-1939) retrospective with some 250 exhibits retraces the development of the Vorarlberg painter and draftsman, highlights his beginnings, thematic phases of his oeuvre and illustrates his works’ artistic quality and technical perfection.

His works enter into a dialogue with a careful selection of creations by German New Objectivity artists such as Albert Birkle, Otto Dix, Alexander Kanoldt, Anton Räderscheidt, Georg Schrimpf and Gustav Wunderwald.

View of the Rudolf Wacker exhibition at the Leopold Museum, Wien. Photo copyright (c) Leopold Museum, Vienna/APA-Fotoservice/Roland Rudolph.

The exhibition catalog

In the catalog, Hans-Peter Wipplinger writes that Rudolf Wacker’s life and work cannot be separated from the social and political events and developments of the 1910s to the 1930s, which shaped and overshadowed his path as a man and artist.

He underlines that the catalog essays illuminate Rudolf Wacker’s complexity as a draftsman and painter, as a readerand author, as an artist and art critic, and not least as a collector and networker. Marianne Hussl-Hörmann outlines the personality and works of the artist who, all his life, sought to document and quantify himself and his artistic work, and to reflect on it in an art critical and art theoretical manner.

Jürgen Thaler examies Rudolf Wacker’s relationship with the art metropolis Vienna, which, during his lifetime, failed to afford his oeuvre the recognition it deserves. Ute Pfanner locates the artist within the manifold and vibrant artists’ associations of the tri-border region on Lake Constance (Austria, Germany, Switzlerand), thus revealing Wacker’s strategic approach to networking and to marketing his art.

In his essay dedicated to Rudolf Wacker’s self-portraits, Herbert Giese traces the psychological nuances of these drawings and paintings from different periods of the artist’s life and oeuvre. Laura Feurle examines Rudolf Wacker’s diaries as well as his drawn and painted images of women, to a critical rereading by elaborating on central areas of his perception of art and the world, in which a liberal sexual morality entered into an ambiguous union with a conservative understanding of gender roles.

Rudolf Sagmeister and Kathleen Sagmeister-Fox view Rudolf Wacker’s still life from a political perspective against the background of the socio-political upheaval especially of the 1930s, fathoming the functions and potential of the recurring motif of children’s drawings in Wacker’s oeuvre.

In another essay, Marianne Hussl-Hörmann offers a panoramic overview of Rudolf Wacker’s “magical” world of things. At the end of the catalogue, select passages from the artist’s diaries enter into a dialogue with his works.

The life and work of Rudolf Wacker

Born in Bregenz on February 25, 1893 Rudolf Wacker was born as the fourth and youngest child of Romedius Wacker, a successful master builder who lived with his family in a villa he had built himself around 1900 with a large garden.

In his catalog essay, Jürgen Thaler writes that Rudolf Wacker left the Bregenz high school prematurely. Following a brief stint at a class for open drawing at the newly established Vocational School for Drawing (Bre- genz Fachschule für Zeichnen) he was rejected by the Vienna Academy. He enrolled at Malschule Bauer, a private painting school, founded in Vienna in 1889. From 1907 onwards, it was headed by the Viennese painter and illustrator Gustav Bauer. When Wacker reapplied for a place at the Vienna Academy the following year, he was again rejected. He left Vienna in late October 1911 for the German city of Weimar, where he attended the Grand-Ducal Saxon Art School (Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule Weimar). His teacher was the Austrian Albin Egger-Lienz (1868-1926), best-known for genre and historical paintings.

In 1914, the outbreak of the First World War turned the life of the young art student upside down. Rudolf Wacker was drafted into the Austrian military, received basic training, was sent to the Eastern front, in present-day Ukraine, where, in October 1915, he was captured by the Russians. He ended up in the Siberian town of Tomsk, where he stayed for most of his five years of captivity.

Jürgen Thaler notes that, in November 1921, having regained his freedom, Rudolf Wacker moved to Berlin for a year of recuperation and reorientation. While he did not manage to gain a foothold in the German metropolis, he did meet the artisan craftswoman Ilse Moebius in Berlin. They married in 1922 in her hometown of Goslar. In order to escape the poverty of an artist’s life in Berlin, the couple moved to Bregenz in the summer of 1923, where they lived at the villa of Wacker’s parents. In November 1923, they went from there to Vienna, where they would stay until July 1924.

Jürgen Thaler underlines that, in the Austrian capital, Rudolf Wacker managed to exhibit his drawings with the most important artists’ associations and in the most renowned galleries of the time. He presented works on paper in exhibitions of the Hagenbund and the Secession, and at important Viennese galleries including Krystall, Würthle and the Neue Galerie.

According to Hans-Peter Wipplinger, Rudolf Wacker’s expressive style reached early climaxes, especially in the medium of drawing. Parallel to the developments in the art scene of the time, but without merely imitating them, he arrived at an independent variant of New Objectivity in the mid-1920s.

View of the Rudolf Wacker exhibition at the Leopold Museum, Wien. Photo copyright (c) Leopold Museum, Vienna/APA-Fotoservice/Roland Rudolph.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger writes that the Expressionist strategies – ecstatic frenzies, emphatic emotionality, heightened idealism and individualism – were no longer able to describe the new reality of the social and political upheaval following the experiences of war. What was required was a new view of the world, shaped by an objective perception of reality. With his fellow artists Georg Schrimpf and Alexander Kanoldt, Rudolf Wacker shared his fascination for the magic in everyday objects, which he managed to render without slipping either into a cold sobriety or into an unbroken romanticism of reality.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger writes that Rudolf Wacker and Otto Dix had as many commonalities as they had differences. While Wacker admired Dix’s razor-sharp criticism of society, his art corresponded to Dix’s more in terms of painting technique than in terms of their pictorial language. In his still lifes of the 1930s, especially, Rudolf Wacker arrived not only at technical perfection but also managed in an unparalleled manner to convey the isolation of things and to allow for the abysses of reality to shine through in a subtle and subversive manner.

Jürgen Thaler notes that, during his stay in Vienna, Rudolf Wacker first presented the intense, gestural and highly complex expressive drawings that are so typical of his oeuvre.

According to Jürgen Thaler, the three works Rudolf Wacker created upon his return to Bregenz, the Self-Portrait with Shaving Foam (Fig. p. 187), the self-portrait as a painter (Fig p. 76) and the Naturalistic Collage (Fig. p. 183), represent not only a farewell to his early understanding of himself as a painter and draftsman but also to his eventful time living in Vienna. They further anticipate what was to come.

Vienna as the city of art and artistic life, of his friends and benefactors, would remain an important point of orientation for the artist even after his return to Bregenz, which was ultimately necessitated once again by financial hardship.

Jürgen Thaler stresses that, during the time of the First Republic (1919-33), Rudolf Wacker did not succeed in drawing attention with his works in Vienna. It was only when the National Socialists seized power in Germany, and a national-authoritarian corporative state was established by Engelbert Dollfuss (Austrofascism) as a result in Austria, that Rudolf Wacker had the opportunity to become active in Vienna again. One of the reasons for this was that the official Austria vehemently tried to build its own Austrian identity in order to disassociate itself from any manifestations of the “greater German idea”. This demand for Austrian art brought many opportunities for visual artists to present their works in various exhibitions, not only in Austria but also abroad.

Jürgen Thaler underlines that Rudolf Wacker did not only participate in the 19th Venice Biennale, but that his Still Life with Two Heads (Fig. p. 257) was one of a total of 100 works by 90 artists shown in 1934 for the opening of the Austrian pavilion in Venice, built by Josef Hoffmann, as part of an exhibition of exclusively Austrian art.

According to Jürgen Thaler, the history of the Central Association of Austrian Visual Artists (Zentralverband der bildenden Künstler Österreichs) during the interwar period, especially during the time of the authoritarian corporative state, needs to be studied in more detail. It served as the umbrella organization for many provincial associations, among them the Vorarlberger Kunstgemeinde, of which Rudolf Wacker was an active member. In 1913, Rudolf Wacker was appointed to the Central Association (Zentralverband) as a representative of the state of Vorarlberg. In 1933, he joined the party Fatherland’s Front (Vaterländische Front), founded by the Austrofascist Engelbert Dollfuss. In 1934, he was appointed the party’s custodian of cultural affairs, and as such was now an official in the service of art and the state.

According to Jürgen Thaler, Rudolf Wacker’s decision to join the party was not an ideological but rather a pragmatic one to further his own interests on a small and large scale. The participations in conferences allowed Rudolf Wacker to travel three times to Vienna (in 1933, 1934 and 1935), where he stayed for weeks. He not only participated in the sessions of the Zentralverband, which were very dull to him, but also reconnected with his old friends from Tomsk, while further using the time to manage his own personal affairs. In addition, he visited nearly all the city’s museums, galleries and art exhibitions.

On one trip, Rudolf Wacker was able to win over the Viennese artists’ association Kunstgemeinschaft for his cause. In March 1934, the association organized the largest exhibition of his works during his lifetime. At the Glaspalast, today’s Palmenhaus at the Burggarten, he was able to present 26 paintings and 20 drawings in a solo exhibition.

Jürgen Thaler writes that, in Vienna in 1935, the driven and ambitious artist learnt firsthand that there was a vacant professorship at the Vienna Academy. Such a position would not only bring him prestige but also financial security. It would solve all his problems. Filled with optimism, as his career was flourishing in the mid-1930s, he talked to the most influential people on Vienna’s political scene, including Otto Ender. The Vorarlberg politician was governor of Vorarlberg, and later briefly held the office of Federal Chancellor. At Christmas 1934, Rudolf Wacker gave him his Small Chinese Still Life (Fig. 08), likely not without a hidden agenda. Via an intermediary, he passed on his CV to Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, the Austrofascist who came to power after the assassination of Engelbert Dollfuss, both opposed to Hitler’s Anschluss plans.

All throughout 1935, everything pointed to Rudolf Wacker winning the position of professor at the Vienna Academy. But all his efforts turned out to be futile. Another man was appointed. Rudolf Wacker’s lifelong dream had died. According to Jürgen Thaler, this spelled the end of Rudolf Wacker’s activities in Vienna. In his last exhibition in Vienna in June 1935, he presented 30 drawings at the Neue Galerie.

In the catalog’s biography, compiled by Laura Feurle, one can read that, in 1936, Rudolf Wacker is offered the job of heading an evening class at the Bregenz vocational school, which he accepts on account of the regular, albeit humble salary at the expense of his freedom to travel.

Laura Feurle writes that Rudolf Wacker is denied drawing after naked models in his nude drawing class owing to the prevalent restrictive sexual morality. But, in private, he continues to work with naked models and creates countless permissive works. During those years, he has some success at home with his small-format flower still lifes, leading to an improvement of the family’s financial circumstances in late 1936.

During a two-month trip through German cities in 1937, Rudolf Wacker visits the Munich exhibition of “degenerate art”. It comes as a shock and has a profound impact on the artist. He openly takes sides with Oskar Kokoschka, who is being defamed in Munich, by calling on the Permanent Delegation– the official representatives of the Secession, Künstlerhaus and Hagenbund – to launch a protest. His request is not only unsuccessful but is never answered. Tha tsame year, he withdraws from the Vaterländische Front, as the party – contrary to his initial hopes – proves unable to push back National Socialism in Austria. Resignedly, Rudolf Wacker increasingly retreats into “inner emigration” and the private sphere.

Two months after the Anschluss, Austria’s annexation by Hitler‘s Germany on March 13, 1938 Rudolf Wacker and some of his friends are subjected to house searches, though hardly any incriminating material is found. The artist had already made provisions, concealing potentially damaging documents and possessions, some of which still haven’t surfaced today. When interrogated by the Gestapo, he manages to refute accusations of communist involvement. Around the same time, his existing heart conditions takes a turn for the worse and results in various attacks, which lead him to seek refuge with his former fellow war prisoner, the physician Dr. Gustl Irresberger in Altmünster on the Traunsee. In July, he is able to return to Bregenz, where he manages to complete several still life paintings.

Though Rudolf Wacker has since been dismissed from all public offices and functions, for instance from his role as head of the Central Association of Austrian Visual Artists, on account of his rejection of the National Socialist regime, his paintings continue to be exhibited in Bregenz and Dornbirn. Laura Feurle notes that the authorities not only fail to detect his works’ political content, but, owing to their artisanal perfection in the style of the Old Masters, even consider them in line with the party’s art policy.

In January 1939, Rudolf Wacker’s health further declines. His brother Romedius has him admitted for treatment to the cantonal hospital in St. Gallen (Switzerland). He is released on March 9 as a palliative patient. On April 19, 1939 he dies at his parental home in Bregenz from his heart condition.

Rudolf Wacker’s relationship with his hometown of Bregenz on Lake Constance was ambivalent all his life. On one hand, it was a safe and familiar haven, both economically and in terms of the closeness to his family, on the other, he suffered from the provincial narrowness and hostile local art critics. He loved the picturesque landscape. But he subtly incorporated criticism of the increasing brutalization of society by means of withered branches, crumbling wall plaster or neglected backyards.

More details and essays in the exhibition catalogue, edited by Marianne Hussl-Hörmann, Laura Feurle & Hans-Peter Wipplinger: Rudolf Wacker. Magic and Abysses of Reality, Leopold Museum, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2024, 23,5 x 28 cm, 336 pages with 260 color illustrations, hardcover, bilingual text in German and English. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the bilingual (English and German) exhibition catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this catalogue/exhibition review of Rudolf Wacker. Magic and Abysses of Reality/Magie und Abgründe der Wirklichkeit have not been put between quotation marks.

Review of the catalog and exhibition Rudolf Wacker. Magic and Abysses of Reality/Magie und Abgründe der Wirklichkeit at Leopold Museum in Vienna added on November 11, 2024 at 14:49 Austrian time.