Switzerland perceives itself as a neutral state. Many Swiss think that their country was not involved in colonialism. But an exhibition at the Swiss National Museum Zurich (Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum Zürich) from September 13, 2024 until January 19, 2025, entitled Colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements, showed that Swiss citizens and companies were globally connected and entangled with colonies established by the seafaring European nations in Africa, the Americas and Asia. Therefore, Switzerland was involved in the colonial system from the 16th century onwards.

The Swiss National Museum Zurich exhibition, which examined Switzerland’s colonial entanglements, is over. But it will be on display in an adapted form at the Château de Prangins from March 29 until October 11, 2026.

The catalog of the same name accompanying the two exhibitions, edited by the Swiss National Museum (Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum): colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements. Published by Scheidegger & Spiess, paperback, 2024, 284 pages with 49 color and 12 b/w illustrations, 16 x 23 cm, 664 grams. ISBN-13: 978-3-03942-211-1. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Krüsi Manager House, Manager House in Deli, Maryland Estate, Karl Krüsi, Deli, 1885. Photograph copyright © Swiss National Museum. Page 142 of the book colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements.

Some Swiss companies and private individuals took part in the transatlantic slave trade, earned a fortune from the trade in colonial goods and exploitation of slave labour.

In addition, Swiss men and women travelled the globe as missionaries. Other Swiss, driven by poverty or a thirst for adventure, served as mercenaries in European armies sent to conquer colonial territory or crush uprisings by the indigenous population. Swiss experts placed their knowledge at the disposal of the colonial powers. Colonial artifacts ended up in Swiss museums, including some of the famous Benin bronzes and other artifacts looted by the British in 1897. The racial theories prevalent at the time, used to justify the colonial system, formed part of the curriculum at the universities of Zurich and Geneva.

The exhibition at the National Museum Zurich and its accompanying catalogue, on which this article is based, draw on the latest research findings and use concrete examples, illustrated with objects, works of art, photographs and documents, to present the first-ever comprehensive overview of Switzerland’s history of colonial entanglement. The exhibition and catalogue also draw parallels to contemporary issues, exploring the question of what this colonial heritage means for present-day Switzerland.

The ten catalogue essays take the traces of colonialism in everyday life in Switzerland as their starting point, examine the trade in enslaved people, the Swiss history of mercenary soldiers, the (transit) trade in goods, the exploitation of nature and the environment, racism, missionary societies as well as Swiss scholarly researchers in colonial settings.

The catalogue’s essay section concludes with a discussion of the structural consequences of colonialism in the Global South, the role of museums as colonial archives, and Switzerland’s diplomatic relations during the decolonization phase. Last, but not least, the catalogue contains a richly illustrated picture section in which some of the exhibits are presented and analyzed.

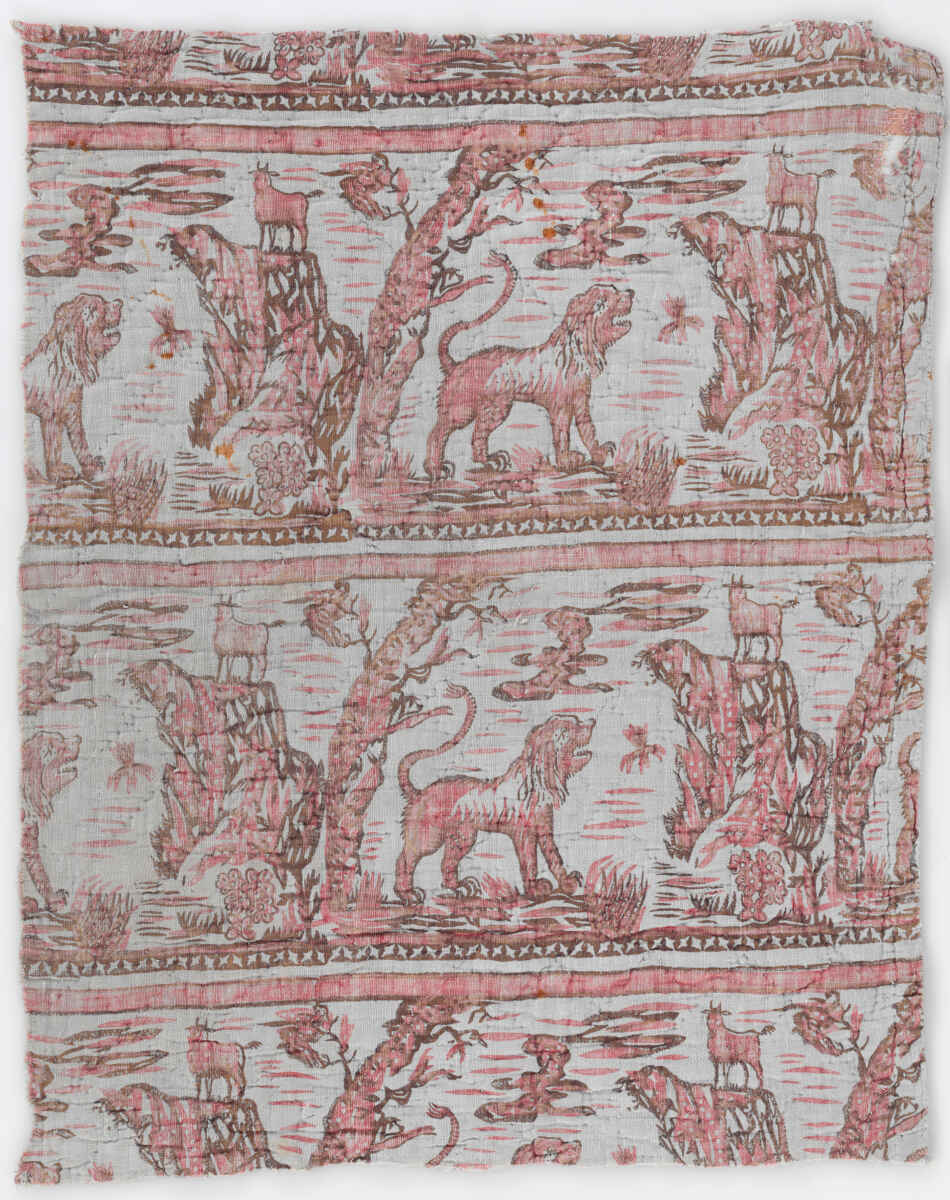

Fabric for the trade in enslaved people, Le lion et la chèvre, Indiennes, Manufacture Petitpierre & Cie., Nantes, late 18th century, woodblock print on cotton fabric. Photo copyright © Swiss National Museum. Page 116 of the catalogue colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements.

The exhibition and catalog present an overview, but try to offer a nuanced picture. Swiss trading companies were commercially involved with enslaved people in the 18th century. Some Swiss participated in the plantation economy on Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), which is still practised in its environmentally damaging form today. Mercenaries from Switzerland fought in the armies of colonial powers. Swiss took part in colonial settlements, missionary work, colonial administrations and science projects in colonial lands. Scientific instruments were developed in Zurich which were used in the 19th century to measure the skulls of “primitive peoples” in order to prove their supposed inferiority. Advertising posters for ethnological expositions known as “human zoos” were being staged as late as 1964!

The exhibition and catalog also show that there was scope for individual action, and that the colonised put up resistance. Some Swiss men and women dedicated themselves to fighting for the abolition of slavery. As missionaries, some Swiss not only preached the gospel, but also actively campaigned for education and medical care.

In her essay, Marina Amstad underlines that without cocoa beans and sugar—both colonial products—the development of the chocolate industry in Switzerland would have been unthinkable.

She mentions Jacques-Louis de Pourtalès (1722– 1814) from Neuchâtel, the founder of the company Pourtalès & Cie, which traded in both Europe and the colonies and owned numerous factories for the production of chintz. These printed cotton fabrics were the most important barter goods in the slave trade, and a significant share was produced by the Swiss cotton industry. Pourtalès not only provided work for a large number of people at his factories, he also made enormous profits from the sale of the fabrics, which were intended, among other things, to be exchanged for enslaved people. In addition, Pourtalès owned plantations in the Antilles, where, with the help of hundreds of enslaved people, he grew mainly sugar beet, along-side coffee, cocoa, and cotton.

According to Marina Amstad, in 1799, Jacques-Louis de Pourtalès was probably the richest man in Switzerland. In 1808, he funded the establishment of the “Hôpital Pourtalès”, a medical facility for the poor, in his hometown of Neuchâtel. Meanwhile, the families of mercenaries, often living in poverty, remained dependent on the pensions, gratuities, and estate payments that were sent from the colonies to the municipalities in Switzerland.

Slave trade, porcelain figure group, Manufaktur Kilchberg-Schooren, Kilchberg, c. 1775. Photography copyright © Swiss National Museum. Page 114 of the catalogue colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements.

In her essay, Jovita dos Santos Pinto explains that an estimated twelve million people were abducted from the African continent between the 16th and 19th centuries. For every enslaved person who arrived in the Americas, as many as five perished while still in Africa, in the process of being hunted down, while being marched to the coast, imprisoned in makeshift huts or chained in the ship’s hold off the coast or during the Atlantic crossing.

The triangular trade meant that Europeans would load their ships with goods in European harbours and then sail to Africa where they exchanged them for human beings purchased from Creole, African, and Arab traders. After crossing the Atlantic they would sell these people into slavery and then reload their ships with goods produced with slave labour. These goods were in turn sold upon their return to Europe.

Jovita dos Santos Pinto stresses that slavery and transatlantic trade were closely linked with the development of capitalism and European imperialism. They had a destructive impact on Indigenous ways of life on both the African and American continents, resulting inthe annihilation not only of people, cultures, and languages, but also—as a result of raw materials extraction and the cultivation of plantations—of animals, plants, and entire ecosystems. Yet it was almost exclusively the cities of the Global North that profited from the value created.

Jovita dos Santos Pinto writes that the territory of (what is today) Switzerland was already integrated in the global economy in the 17th century. Especially from the 18th century onwards, Swiss were directly or indirectly involved in the trade in enslaved people. Products based on slave labour changed consumer habits in Swiss cities and rural communities. A remarkable number of Protestant Swiss families became involved in slavery as traders, investors, plantation-owners, or settlers.

These are just a tiny number of insights from the catalog, edited by the Swiss National Museum (Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum): colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements. Published by Scheidegger & Spiess, paperback, 2024, 284 pages with 49 color and 12 b/w illustrations, 16 x 23 cm, 664 grams. ISBN-13: 978-3-03942-211-1. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

On the catalogue cover as well as on page 6 (reproduced below), you can find the emblem of imperial power, a late 19th century Pith helmet, probably Congo. Photo copyright © Musée d’ethnographie de Genève (MEG), photo: M. Johnathan Watts. Page 6 of the catalogue colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this exhibition and catalogue review of colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements are not put between quotation marks.

Catalogue and exhibition review of colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements added on December 4, 2025 at 11:13 Swiss time.