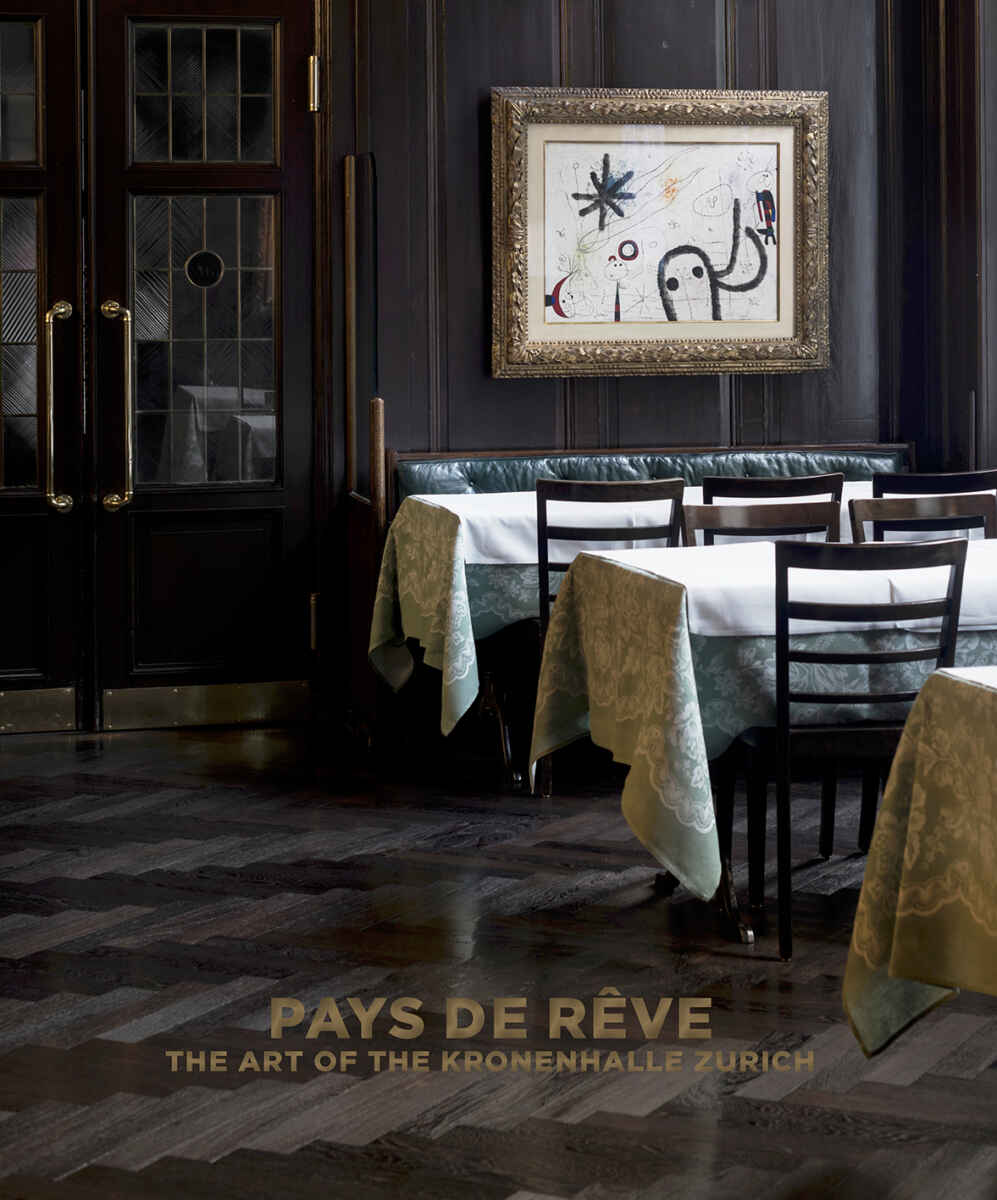

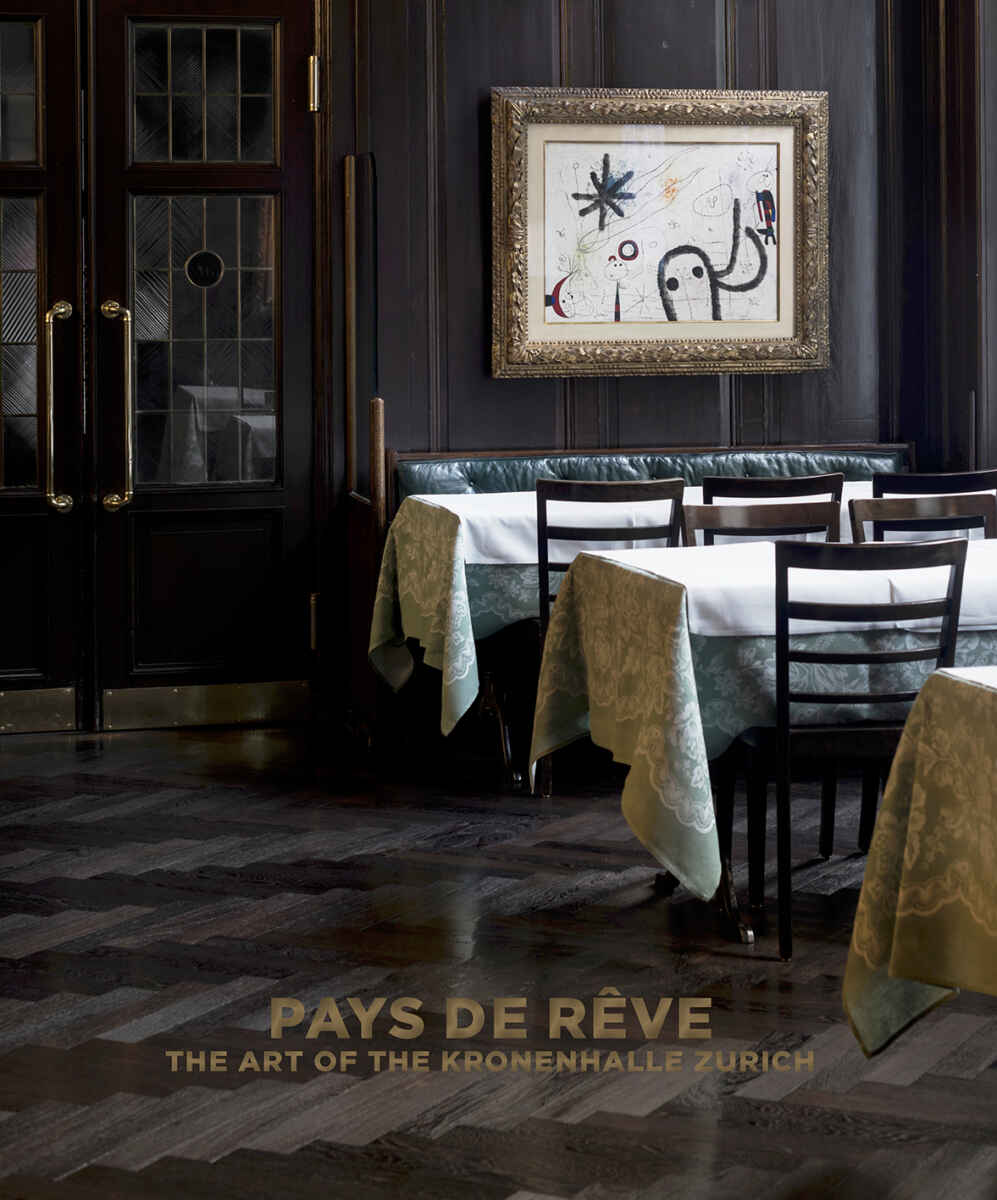

The famous Kronenhalle is a legendary restaurant with brasserie, dining halls and bar in Zurich, Switzerland. Joan Miró called it “pays de rêve”, hence the title of a new, richly illustrated book, edited by Sibylle Ryser and Isabel Zürcher, which focuses on the restaurant’s artistic heritage: Pays de rêve: The Art of the Kronenhalle Zurich, Scheidegger and Spiess, October 2024, 128 pages with 165 color and 20 b/w illustrations, 22 x 26.5 cm. English edition ISBN 978-3-03942-227-2. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

At the tender age of 16, Hulda Zumsteg (1890–1984) moved from the nearby city of Winterthur to Switzerland’s economic capital Zurich. She had just fifty rappen in her pocket. Towards the end of her life, in 1970, aged 80, she oversaw more than 70 staff at the Kronenhalle’s premises at Rämistrasse 4. She drew in guests from literature, music and theatre circles to her restaurant and brought them together with Zurich’s bourgeoisie.

Her son, the successful silk merchant and art collector Gustav Zumsteg (1915–2005), contributed to the Kronenhalle’s success. On December 28, 1962 Joan Miró wrote to his friend and supporter Gustav Zumsteg: “I am taking the liberty of sending your mother a gouache that I am dedicating to her with all my heart.” This seasonal greeting illustrates the commitment with which the collector Gustav Zumsteg related to the artists and creative minds of his time, a commitment he shared with his mother Hulda. It is in the same letter that Miró calls the Kronenhalle a pays de rêve – a land of dreams.

Photograph on page 34. Still life: door with emblem © photo copyright Donata Ettlin.

The book offers a brief history of the Kronenhalle and its art collection. The Kronenhalle was not conceived as a restaurant from the start. In 1842, prior to the backfill of the lake that created today’s Bellevueplatz, the property was built as a residential house with a barn and shed, also in order to accommodate the elegant neighbouring Hôtel de la Couronne with space for its guests’ carriages.

In 1862 only, the Kronenhalle became a restaurant. With its position on Lake Zurich (Zürichsee), it quickly became a meeting point for Zurich’s high society. It was frequented by painters such as Arnold Böcklin and writers including Gottfried Keller and Conrad Ferdinand Meyer.

In 1924, Gottlieb and Hulda Zumsteg purchased the Kronenhalle, and with this the husband-and-wife owners relocated from the Mühle in the Niederdorf to the edge of the old town. Having been unoccupied for several years, the property was derelict. It needed great personal commitment by the Zumsteg couple to turn the business around. Hulda remembered the years after the First World War: “for Zurich, it was a time when money was earned easily and spent just as easily.”

Under their ownership, famous guests included writers, painters, fashion designers, film directors and other artists, including James Joyce, Coco Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Chagall, Frederico Fellini, Max Frisch, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Carl Zuckmayer and many others.

In the book, one learns that the decorative frieze above the brasserie’s wooden wallpanelling shows the emblems of the traditional Zurich guilds as well as new guilds formed upon Zurich’s expansion. Yet the Kronenhalle never functioned as a guildhall. The restaurant’s nod toward Zurich’s guild society is rather based on the annual ritual of the guild’s spring gathering called Sechseläuten (the six o’clock ringing of the bells), which brings its gregarious after party to the Kronenhalle.

In 1931, Hulda Zumsteg’s son Gustav turned 16. At the studio of his mother’s tailor, he discovered his passion for silk. He started a business apprenticeship with L. Abraham & Brauchbar Co. Seiden AG. As a so-called ‘converter’ business, the company designed fabrics, commissioned select Swiss factories for their production, then distributed them to retailers and individual designers. By producing printed silk for haute couture and prêt-à-porter, Gustav Zumsteg later turned Abraham AG into a leading global label for exquisite fabric design.

The Kronenhalle’s guestbook proves that, by the 1930s, the restaurant had become a melting pot of cultural bohemians and the social elite. Zurich’s music, literary and art scene met at Rämistrasse 4 for lively exchanges and contemporary debates. Café Odéon, once a meeting point for the Dada circle and situated just across the road, also remained a favourite spot amongst the town’s artistic celebrities.

A stone’s throw away are the music theatre (today the Zurich Opera House) and the Pfauen theatre at Heimplatz (today called Schauspielhaus), whose anti-Fascist programme was able to withstand violent animosity thanks to a shareholder company founded in 1938. The Schauspielhausthus started writing history as a stage for émigré artists; its ensembles were always loyal guests at the Kronenhalle.

Photograph on page 59. Still life: basket with bread © photo copyright Donata Ettlin.

In 1940, Gustav Zumsteg was among those who helped James Joyce find refuge in Zurich, where he died in January 1941. Still during the Second World War, in 1943, Gustav, as head of the Paris franchise of Seiden AG L. Abraham & Co, discovered his passion for French culture. France not only inspired the design of his fabrics, but led him to start reading History of Art part time at the École du Louvre. In addition, he visited museums and galleries. Traditional and contemporary visual arts concepts influenced his textile designs. Gustav met Aimé and Marguerite Maeght in Cannes, where the lithographer and future publisher had founded his own printing house in 1930. Pierre Bonnard ordered a poster to be printed by Aimé Maeght and found him to be an exceptional colourist. The encounter marked the beginning of many collaborations with artists, amongst them Henri Matisse, Georges Braque and Joan Miró.

“We were all young then and without money,” Gustav Zumsteg said retrospectively. “We would forge our careersonly later. The Maeghts with their pictures and I with my silk.” The friendship between Maeght and Gustav was based on their mutual respect for the visual arts. At this period, Gustav started his art collection.

Meanwhile, his mother Hulda kept a keen eye on all Kronenhalle guests. During the Second World War, the restaurant featured a students’ table where everybody drank a lot of beer but ate only very little. Hulda concluded that this couldn’t be good for those young stomachs, went to the kitchen, had them prepare a big pot of meat soup, added a few chopped sausages and offered it to the youngsters. Most of them would eventually grow into men “of position and authority” who would stay loyal to the Kronenhalle.

Photograph on page 70-71. Work by Chaïm Soutine © photo copyright Christian Flierl.

During the Second World War, many artists left occupied Paris for the south – creating favourable conditions for an emerging market in the works of Classic Modernism. After the war, for the opening of their Paris gallery in rue de Téhéran, Aimé and Marguerite Maeght organized a solo exhibition of works by Henri Matisse in December 1945.

By that time, for Gustav Zumsteg, the Maeghts and many associated artists had become a second family: “I believe I could have become one of the most important art dealers, because at one point I was enjoying the unrestricted trust of great artists. But I avoided dedicating myself completely to art dealing, as I realised I was too shy for it.” Gustav also noted: “It was Bérard who introduced me to le Tout-Paris of the time.” An admired scenographer, artist, fashion illustrator and designer, Christian Bérard provided Gustav with access to many personalities in the worlds of art and fashion.

For the evening gowns of his March 1953 show, Balenciaga chose a cuir de soie by Abraham. This was a resounding success for Swiss textile production and fabrics created by Gustav’s business. His travels led him into the studios of fashion designers in Paris, New York, London, Rome and Madrid. He was working with Cristóbal Balenciaga, Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, Hubert de Givenchy and Yves Saint Laurent. Designs using Abraham fabrics dressed celebrities from the cinema and theatre world, politicians and European aristocrats.

In the meantime, at Zurich’s Kronenhalle, the menu, initially characterized by a Bavarian chef, was enlarged by specialities from Gustav’s business destinations, but remained loyal to its hearty core.

In 1957, following the death of his stepfather Gottlieb Zumsteg, Gustav took over the management of the famous Kronenhalle and integrated his growing art collection into various rooms, thus establishing “the world’s most culinary museum” and a unique “piece of hospitality art”. Top works of Classic Modernism such as Henri Matisse’s Les huîtres, Marc Chagall’s Les Glaïeuls and Joan Miró’s La table (Nature morte au lapin) formed the background to banquets, family gatherings and business lunches. In addition, they traveled as loans to exhibitions worldwide.

Photograph on page 79. Still life: table with napkins © photo copyright Donata Ettlin.

In 1964, as a tribute to their son Bernard, who died in childhood, Aimé and Marguerite Maeght opened the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. There, hotel Colombe d’Or decorated its restaurant with original works. This has probably given Gustav Zumsteg an early incentive to bring life and art as close together as possible, to be shared permanently with the guests of the Kronenhalle.

In 1965, the Zumstegs acquire a former hairdressing salon in the neighbouring property. Against his mother’s initial resistance – she fears for the solid, civilized reputation of her restaurant – Gustav decided to open a bar. He commissions Robert Haussmann to design the interior, and Diego Giacometti, the furniture. The leather seating and wall coverings are dark green, and the mahogany panelling reminiscent of a ship’s interior. Thanks to its unique cocktails, the Kronenhalle Bar becomes a leading address.

Gustav Zumsteg had promoted the Alberto Giacometti Foundation when it was established at the Kunsthaus Zurich in 1965. He was a member of the Zürcher Kunstfreunde museum association and employed his contacts for the benefit of the Kunsthaus.

Since the departure of Ludwig Abraham in 1968, Gustav had been the sole owner of Abraham AG and an influential figure in the international market for decorative fabrics. On his mother’s 80th birthday in 1980, Gustav Zumsteg donated Chagall’s La fenêtre sur l’île de Bréhat to the Kunsthaus. This marked the beginning of a longlasting initiative for the artist. Gustav Zumsteg became the driving force behind the expansion of Zurich’s inventory of Chagall paintings, which was made public in a specially conceived hall in Nember 1973, comprehensively representing the artist’s oeuvre. Hulda died in 1984.

Photograph page 80. Still life: table with glasses © photo copyright Donata Ettlin.

In 1985, Yves Saint Laurent celebrated 25 years of collaboration with Abraham AG and Gustav Zumsteg at the Kronenhalle. Abraham had designed numerous creations exclusively for the Paris couturier. Yves Saint Laurent stated: “His fabrics are half my fashion.” Gustav Zumsteg added: “Collaborating with him comes close to a miracle, a permanent affinity between materials and colours.” In addition, the Swiss supported the 1983 retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art entitled Yves Saint-Laurent – 25 Years of Design, the Met’s first exhibition about a living fashion designer.

Gustav Zumsteg decided that, after his death (in 2005), masterpieces of his collection would enter the public collection of the Kunshaus, including still lifes by Henri Matisse, Chaïm Soutine and Georges Braque.

In 1995, four major works from Gustav’s collection were auctioned at Christie’s London: La table (Nature morte au lapin) by Joan Miró, Tête de femme by Picasso, Les Glaïleuls by Marc Chagall and Table de cuisine by Georges Braque. The proceeds went to the Gustav and Hulda Zumsteg Foundation. The sale of such prestigious works evoked rumours about the declining business of Abraham AG. Gustav faced accusations of having run his business too much on artistic principles, thereby neglecting the increasingly complex conditions of the textile and fashion market. No longer the sole owner since the mid-1990s, Gustav had allocated private funds and granted loans to the business against his adviser’s opinion.

In November 2002, Abraham AG had to declare bankruptcy and was liquidated. To save his legacy, Gustav Zumsteg privately bought the company archive out of the bankruptcy assets. He transfered the parts of the sample books and designs he considered museum worthy to the Hulda and Gustav Zumsteg Foundation. In 2007, he donated this inheritance, together with a comprehensive collection of press coverage, to the National Museum Zurich. Following expert cataloguing and appraisal, the bequest was presented in the exhibition Soie Pirate in 2010.

Gustav Zumsteg died in 2005. Since his death, the Kronenhalle has been run by the Zumsteg Foundation, which granted the works of art to the restaurant as permanent loans. Works by Beuys, Braque, Chagall, Diego and Giovanni Giacometti, Léger, Picasso, Miró, Soutine, Varlin and others can still be admired at the restaurant.

This article is based on the book, edited by Sibylle Ryser and Isabel Zürcher: Pays de rêve: The Art of the Kronenhalle Zurich, Scheidegger and Spiess, October 2024, 128 pages with 165 color and 20 b/w illustrations, 22 x 26.5 cm. English edition ISBN 978-3-03942-227-2. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review of Pays de rêve: The Art of the Kronenhalle Zurich have not been put between quotation marks.

Pays de rêve: The Art of the Kronenhalle Zurich book review added on April 17, 2025 at 14:32 Swiss time.