The worldfamous Benin Bronzes in the British Museum are part of thousands of artefacts looted in 1897 by the British army in Benin City, the capital of the Kingdom of Benin, located in what is now Nigeria. Subsequently many of the plundered works of art found their way into museums around the globe via the international art market.

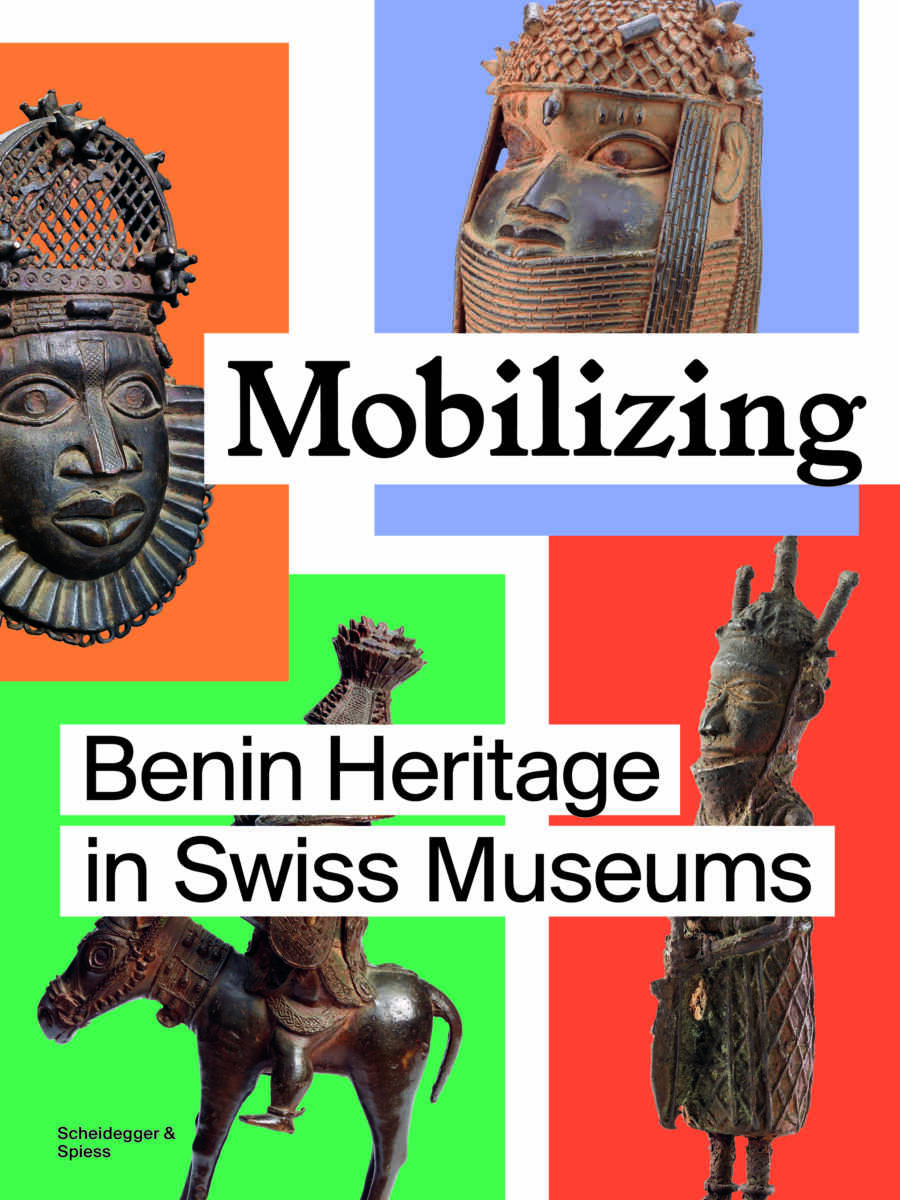

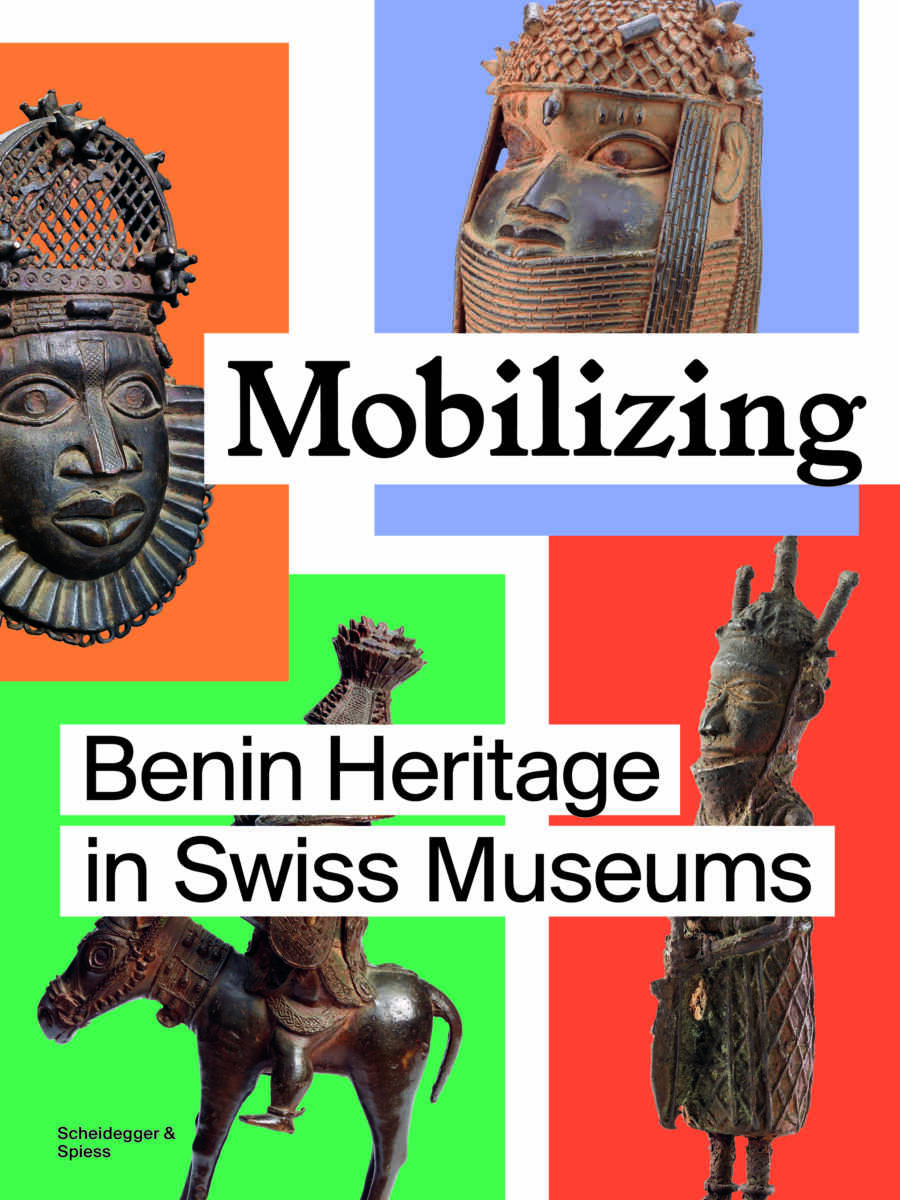

The Benin Initiative Switzerland (2021–24) was a project focusing on provenance research on artefacts from the Kingdom of Benin in Nigeria that are held in eight public museums in Switzerland. The book Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums sums up their findings.

Esther Tisa Francini, Alice Hertzog, Alexis Malefakis, Michaela Oberhofer (editors): Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2024, 120 pages with 121 color and 11 b/w photographs/illustrations. ISBN-10: 3039421980. ISBN-13: 978-3039421985. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

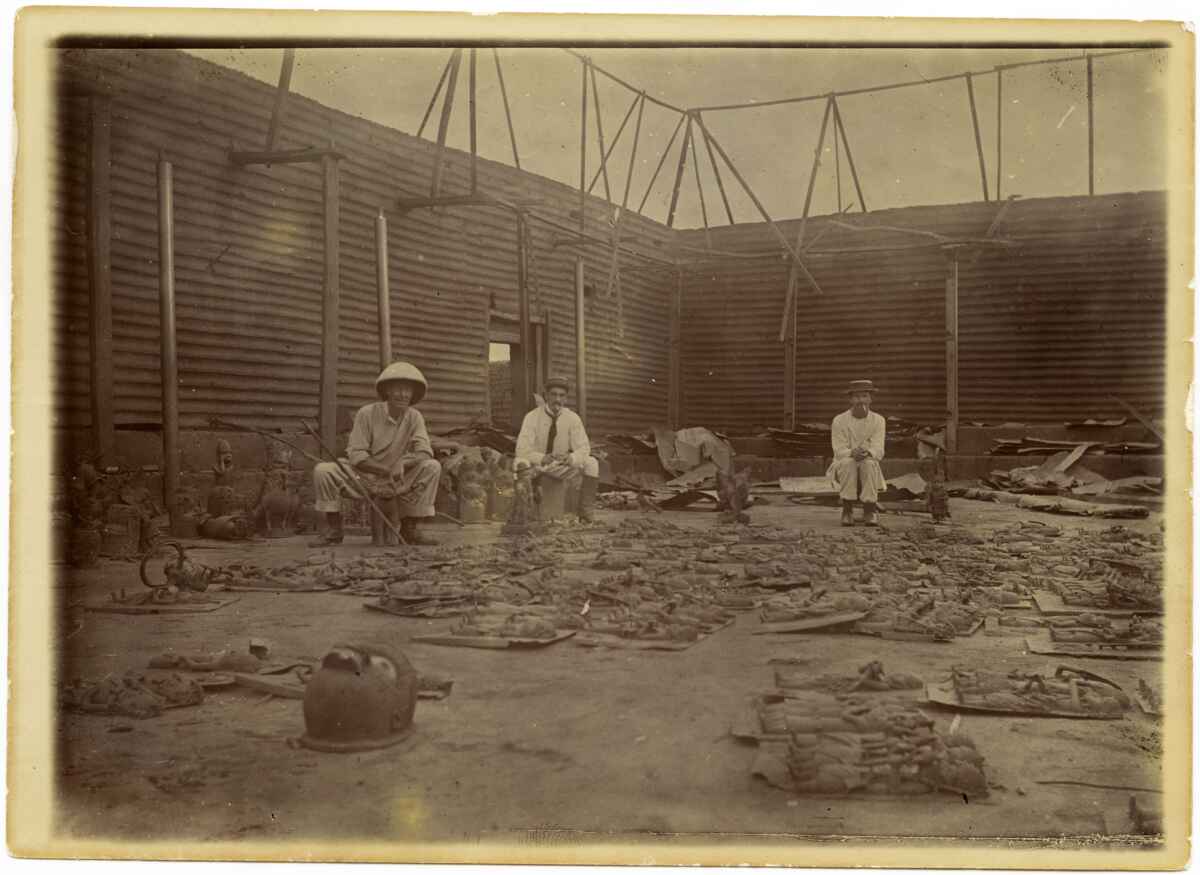

The interior of the Royal Palace in Benin after its destruction in 1897, with Captain C. H. P. Carter, F. P. Hill, and an unknown person (left), Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1998.208.15.11. Page 10 of the book Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, published by Scheidegger & Spiess.

The eight Swiss museums, which are part of the Benin Initiative Switzerland, are: Museum Rietberg, Bernisches Historisches Museum, Kulturmuseum St. Gallen, Musée d’ethnographie Genève, Musée d’ethnographie Neuchâtel, Museum der Kulturen Basel, Museum Schluss Burgdorf, Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich.

In 1897 the British looted and burned down the king’s palace. Between 3,000 and 5,000 objects were stolen from the palace. As soon as the looted objects arrived in British ports in 1897, the works were sold on the art market on behalf of the Foreign Office, via fairs, auctions, and dealers. Merchants, colonial officials, and members of the military also disposed of the possessions they had looted or acquired in Nigeria, putting them on the market immediately after 1897 or selling them at a later date.

Some works ended up in Switzerland. Of the 96 works in Swiss museums examined by the Benin Initiative Switzerland, 21 belong to the category “looted” and 34 to the category “most likely looted”.

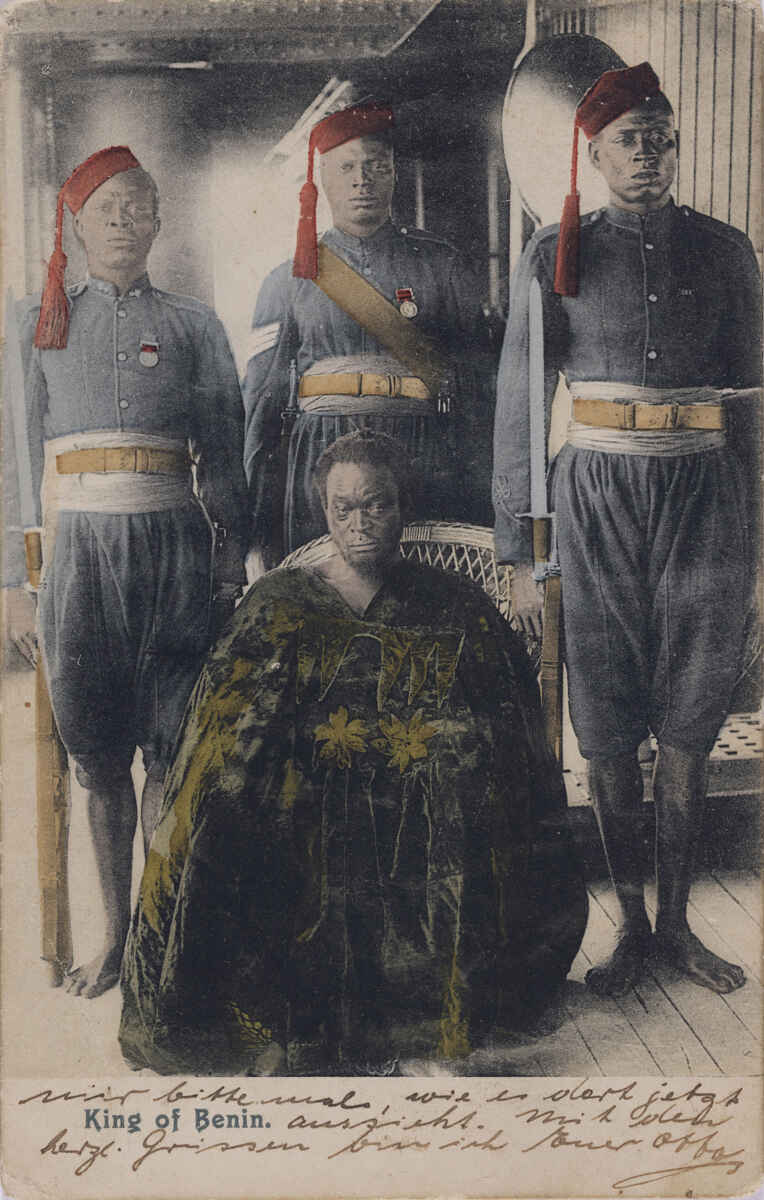

Jonathan Adagogo Green, 1897 postcard showing Oba Ovanramwen, the 35th Oba (king) of the Kingdom of Benin, on board the yacht Ivy on his way into exile in Calabar, where he died in 1914 at the age 54. Photograph copyright © Museum Rietberg, photo by Rainer Wolfsberger. Page 35 of the book Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, published by Scheidegger and Spiess.

This book by the Benin Initiative Switzerland is divided into three sections. The first provides an overview of the methods and process of the Benin Initiative Switzerland, the complex history of Benin, and the country’s cultural heritage with a focus on Nigerian perspectives. The second section examines the provenance of the Benin artefacts and their tangled histories. It presents specific objects from each museum, showcasing research results from the Benin Initiative Switzerland and illustrating case studies from the established categories. Object biographies illustrate the artifacts’ tra-jectories from Benin to Swiss museums and provide contextual information on the people involved, the events that happened, and the circumstances of acquisition.

The third section presents various collaborations that have emerged from the Benin Initiative Switzerland, ranging from commissioning Nigerian contemporary artists, visualizing provenance data, and questioning colonial history to participative research projects with Swiss Edo diasporas and co-curating with Nigerian scholars and designers.

The result of this project is the Joint Declaration of the Swiss Benin Forum on the transfer of ownership of objects looted and likely to have been looted in 1897. The goal is to enable social justice through repatriation and rebuilding trust with communities who no longer just want to be collected. The full text of the Joint Declaration can be found on pages 22-25 of Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums.

Reverse of the pendant hip mask showing the Museum Rietberg inventory number and the number from the antique dealer the auctioneer William D. Webster. Photograph copyright © Museum Rietberg, photo: Rainer Wolfsberger. Page 81 of the book Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, published by Scheidegger & Spiess.

For centuries, hip masks have been part of the ceremonial regalia worn by palace officials in the Kingdom of Benin. The pendant hip mask from page 81 was commissioned from the Royal Guild of Bronze Casters by the Oba and was kept in the palace in Benin until the British punitive raid of 1897. It was not until around 1900 that the hip mask acquired a monetary value as loot, and in 1902 it was sold at the J. C. Stevens Auction Rooms. One of Stevens’s major clients was the auctioneer and dealer William D. Webster. He most likely sold it to Hans Meyer, a researcher and collector from Leipzig, who had exhibited his collection at the city’s Grassi Museum. The mask thus became both a museum object and a focus of scholarly research. Later, Meyer sold the hip mask to Ernst Heinrich, a German dealer and private collector, in whose family it remained as a collector’s object for decades. After the Heinrich family broke up the collection, the mask found its way via the art trade into the possession of the Museum Rietberg. This acquisition was made in connection with the touring exhibition Benin: Könige und Rituale höfischer Kunst aus Nigeria (Benin: Kings and Rituals), which was shown in Vienna, Berlin, Paris and Chicago in 2007/2008. Unlike today, the Webster provenance was considered a seal of quality when the mask was purchased in 2011—a hallmark of an old work made before 1897.

Workshop of Phil Omodamwen, Nigeria, Benin City, March 26, 2022. Photograph: Alice Hertzog. Page 1 of the book Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, published by Scheidegger and Spiess.

Esther Tisa Francini, Alice Hertzog, Alexis Malefakis, Michaela Oberhofer (editors): Mobilizing: Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2024, 120 pages with 121 color and 11 b/w photographs/illustrations. ISBN-10: 3039421980. ISBN-13: 978-3039421985. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

If you read German, have a look at the articles about Benin: Könige und Rituale höfischer Kunst aus Nigeria as well as Benin: geraubte Geschichte. Museum am Rothenbaum in Hamburg.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review of Mobilizing. Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums are not put between quotation marks.

Book review of Mobilizing. Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums added on December 2, 2025 at 15:04 Swiss time.

P.S. Writing this article, I’ve learned that artifact is American English, artefact is British English.