Already since September 4, 2025 and until January 18, 2026 the Leopold Museum in Vienna presents the exhibition Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900. Curated by Matthias Dusini and Ivan Ristić, the show examines the diverse occult-reformist milieu in Vienna at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. But unlike Paris, Prague or Leipzig, Vienna was not among the centers of occultism.

In the catalogue Prologue, Leopold Museum Director Hans-Peter Wipplinger explains that other variants of modernity existed alongside the established notion of Viennese Modernism, as expressed in the impressive buildings by the architect Otto Wagner and his pupils or in the allegorical mysteries, tending towards transcendence, found in Gustav Klimt’s paintings.

Hidden Modernism focuses on the subcultures which fed off the ideas of spiritualism, occultism, esotericism and many other movements that opposed the materialism of the Gründerzeit era. It was a time of (spiritual) renewal and awareness, accompanied by utopianism, theosophical and ecological ideas, the quest for the “new man” and their free development as individuals. Rainer Maria Rilke summed it up with the catchphrase “you must change your life!”

The exhibition highlights parallels to the present day, which is equally characterized by the quest for a better future and hidden (“occult”) truths.

Hidden Modernism is divided into thematic sections, focusing on the various movements, networks and protagonists. The show features some 180 works by 83 artists, and spans the period from the 1860s to the 1930s. It includes photographs, posters, books, manuscripts, as well as display items, such as gymnastics equipment and clothing.

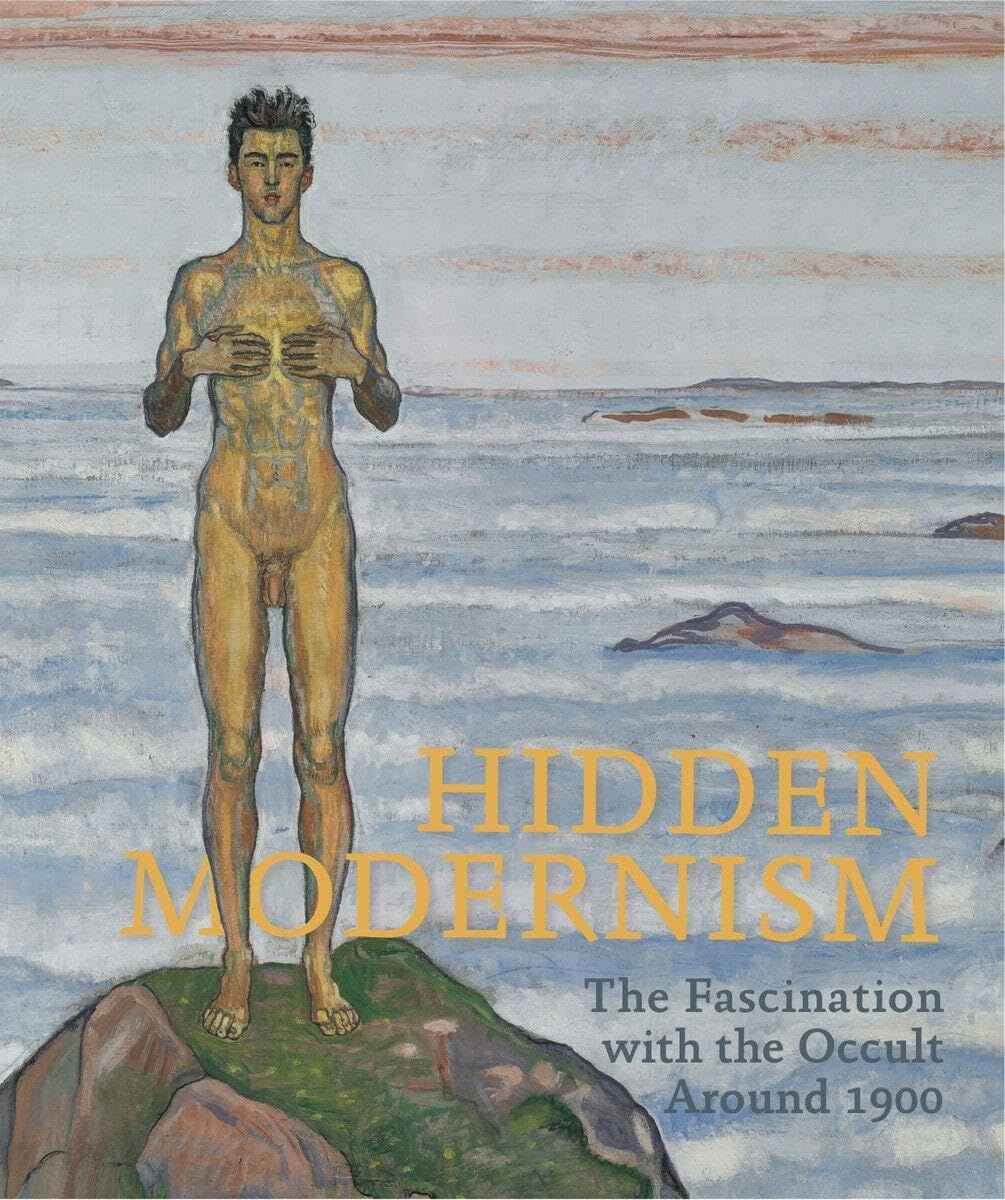

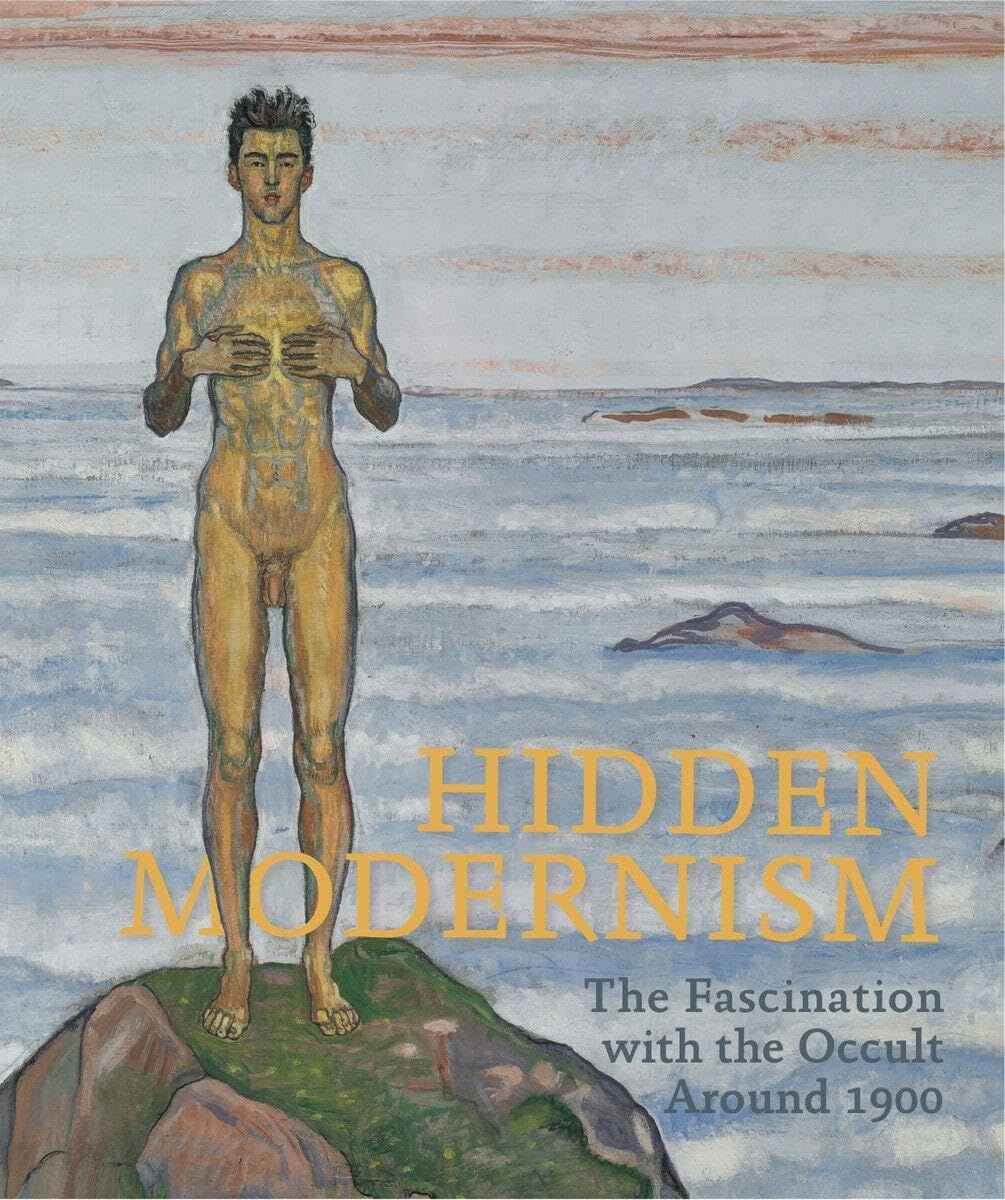

The catalogue, edited by von Matthias Dusini, Ivan Ristic and Hans-Peter Wipplinger: Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900. Hardcover, Leopold Museum, Vienna, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, Köln, 295 pages with roughly 230 illustrations, 23.5 x 28 cm. ISBN-10: 3753308803. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English edition of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900. Exhibition view. Photo copyright © Oliver Ottenschläger/Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Around 1900 people witnessed rapid progress in engineering and science brought about by industrialization. This new dynamic pace of daily life often collided with constrictive conventions. The negative impacts of urbanization led to the call “back to nature!”

Women’s and youth movements were created. There was an upsurge in mountaineering and naturism. In addition, vegetarianism, naturopathy, the propagation of reform clothing, the yoga mouvement, new forms of dance and gymnastics were all expressions of a changing society too. People’s body awareness and attitude towards life changed. The reform mouvement raised ecological concerns. The aim was to live in harmony with nature. Spiritism and hypnosis were on vogue.

Ivan Ristić, co-curator of the exhibition Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900, does not ignore the dark sides of these reformist aspirations. The ethnic-popular variant of Theosophy did not merely strive for universal brotherhood. The fraternization of humanity went hand in hand with a racial theory that called for the primacy of the so-called “Aryan race”, crude Darwinist racial theories.

Some within the reform movement propagated the rejection of anything that supposedly contradicted “people’s natural national character”, causing it to be defamed as “degenerate”. Far-right racist esotericism cast an unmistakable shadow over this period especially in Vienna, where Adolf Hitler spent part of his youth and early adulthood, and where he was confronted with racism, anti-Semitism, and German nationalism for the first time.

Adolf Ost (active around 1859–1870): Apparition of a Spirit (before 1864). Albumen paper on mounting cardboard, 37.4 × 44.8 cm, Albertina, Vienna. On permanent loan from the Austrian Federal Education and Research Institute for Graphics. Photo copyright © Albertina, Vienna. Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900 catalogue page 279.

In the exhibition, select works by eminent artists such as František Kupka, Wassily Kandinsky and Johannes Itten illustrate occultist-inspired paths to abstraction.

Numerous artists, philosophers and natural scientists were united by their profound skepticism towards the ramifications of the industrial revolution and the belief in progress.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger notes that the newly emerging social, physical, mystical and political reform movements opted to leave behind the material reality, which they believed to be wrong, in order to search for spiritual realizations.

These prophets of a new era of mankind wanted to attune themselves to a cosmic world soul, looked for alternative ideas and moral concepts, and sought to free their living environment from restricting conventions.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger points to spiritualism, Theosophy, the hype surrounding occultism, which symbolizes an era marked by contradictions. The exhibition and the catalogue show the often glorified era of Viennese Modernism in its ambiguous position between progress and reaction.

The museum director draws parallels with our times, not least in terms of a new hostility towards science that revealed itself in a drastic manner during the corona pandemic. I would add that, on one side, the German Green Party embrazes the science behind electric cars, wind and solar energy and, on the other hand, even some prominent Green Party members support the pseudoscience of homeopathy, they believe in the use of homeopathic dilutions and globuli.

Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900. Exhibition view. Photo copyright © Oliver Ottenschläger/Leopold Museum, Vienna.

In his introductory catalogue contribution, the religious scholar Karl Baier positions the Danube metropolis within the Occult International and introduces readers to eminent protagonists of this movement’s relevant networks in Vienna. The contemporary historian Michaela Lindinger, who works as a custodian at the Wien Museum and has supported the realization of this exhibition project as a curatorial advisor, uses the example of Vienna to show spiritualism as a reflection of human hopes and irrational passions but also as a foray of esoteric science. In her second essay, Michaela Lindinger presents the protagonists of the Viennese reform movement.

The literary scholar Kira Kaufmann has dedicated her contribution to the phenomenon of automatic writing – on the one hand as a form of self-empowerment of women and on the other as a possible object of study of psychoanalysis which emerged around 1900.

The musicologist Therese Muxeneder focuses on Theosophy, spiritualism and astrology in the oeuvre and correspondence of Arnold Schönberg. The Austrian composer focused his artistic endeavors on exploring new means of expression, such as resonances from within the subject. He defined his work as an interplay between conscious logic, an intuitive sense of form and unconscious emotions – as a trial of strength between construction and the investigation of internal processes. Distancing himself from the conventions of composition, Arnold Schönberg ventured into new structural and ideological realms from 1908 onwards. He left behind an aesthetic reproduction of reality and strove for “supreme unreality” or “the utmost unreality”.

Astrid Kury, art historian and head of the Akademie Graz, investigates occultist influences in the oeuvres of Edvard Munch, Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele. The search for the “other reality” became programmatic for art around 1900. Munch for instance explored the “other reality” through introspection, through his “psychic naturalism”.

Laura Feurle, collection curator at the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, addresses new dance as a realization of the basic idea of life reform to establish a balance between nature and the individual.

The exhibition curator Matthias Dusini retraces the steps of the Viennese mathematician Oskar Simony, whose work exemplifies the interactions between science and parascience typical of this time. The other curator, Ivan Ristić, examines to what an extent early Modernism succeeded in formulating the prophecies of ancient heroes and the concept of temples. Artists of the 19th century were only too happy to make affirmative recourse to ancient mythology and figures that had survived the Christian-informed Middle Ages to be reactivated in modern times – whether they were used to celebrate progress or to incarnate human virtues.

Among the great innovators of the Gründerzeit era was Richard Wagner. He proclaimed the ideal of the universal work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk). This was of vital importance to the Vienna Secessionists surrounding Gustav Klimt. Artists such as Eduard Veith and Koloman Moser captured scenes from Wagner’s operas Der Ring des Nibelungen and Tristan und Isolde on canvas.

Vienna was the city where Wagner’s fanatical anti-Semitism fell on fertile soil. His 1850 essay Judaism in Music provides a particularly drastic example of racist agitation.

Another great innovator, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, was initially close to Wagner, who was a generation older than him. Unlike Wagner, however, Nietzsche did not believe in the consolations of metaphysics but instead demanded that Christian morality, as well as science’s claim to truth, had to be overcome. His nihilistic doubts about the meaningfulness of existence led him towards the idea of the “New Man”, the superhuman (Übermensch). The new “Übermensch” was to surpass himself and find his way back to a Dionysian rapture, find salvation in his own body. Nietzsche was especially interested in Prometheus, a figure from Greek mythology, who was punished by the gods for giving fire to man, and whom the philosopher regarded as a symbol of man’s revolt against divine authority and the discovery of their own creative power. In addition, Nietzsche was inspired by Eastern philosophy and Zarathustra. Nietzsche’s world of thought provided the breeding ground for the life reform movement. At some point in their lives, both Wagner and Nietzsche were vegetarians.

Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900. Exhibition view. Photo copyright © Oliver Ottenschläger/Leopold Museum, Vienna.

The catalogue cover (at the end below) shows an oil painting by the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918): A View to Infinity III (1903/04). Oil on canvas, 100×80 cm, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne. Acquired in 1994. Photo copyright © MCBA/Lausanne.

The painting’s catalogue entry stresses that Ferdinand Hodler exerted a significant influence on the exponents of Viennese Modernism, for instance on Koloman Moser. In 2022, the Kunsthaus Zurich exhibition Hodler, Klimt und die Wiener Werkstätte partly examined Hodler’s relation with artists from Vienna, but it was not focused on the Occult.

The Leopold Museum’s catalogue entry underlines that the painting A View to Infinity III, which was exhibited at the 19th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession in 1904, shows one of those “figures we cannot get bored of, as we seem to understand them but can never fully grasp them” (Ludwig Hevesi). Hodler’s son Hector was the model for the naked youth who stands high above the valleys, which are darkened by a sea of clouds. His gaze is that of an awakened, who has risen above all earthly hardships, his hands, pressed to his chest, referring to his heightened sense of inwardness. In this work, Ferdinand Hodler united the Symbolism of his time with German Romanticism. The New Man is shown at eye level with the viewer, but at the same time in a moment of transfiguration borrowed from Christian iconography. Though Hodler’s activities in the Rosicrucian milieu (Christian mystics) were limited to the 1890s, his rejection of everyday-life realisms remained a characteristic of his oeuvre throughout his life.

These are just a few takeaways from the catalog, edited by von Matthias Dusini, Ivan Ristic and Hans-Peter Wipplinger: Hidden Modernism: The Fascination with the Occcult Around 1900. With contributions by Hans-Peter Wipplinger, Karl Baier, Michaela Lindinger, Matthias Dusini, Kira Kaufmann, Ivan Ristić, Astrid Kury, Therese Muxeneder and Laura Feurle. Hardcover, Leopold Museum, Vienna, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, Köln, 295 pages with roughly 230 illustrations, 23.5 x 28 cm. ISBN-10: 3753308803. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English edition of this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this exhibition and catalogue review of Hidden Modernism are not put between quotation marks.

Catalogue and exhibition review of Hidden Modernism added on December 7, 2025 at 21:08 Austrian time. Updated at 21:11 Austrian time: 83 and not 85 artists.