At 12 rue Cortot in Montmartre, Paris, once lived, worked and and gathered many famous artists. Among them was Auguste Renoir who, in 1876, painted at rue Cortot masterworks such as the Bal du moulin de la Galette, La Balançoire and the Jardin de la rue Cortot. Other artists include the Fauves Emile-Othon Friesz et Raoul Dufy as well as the writers Léon Bloy et Pierre Reverdy. Suzanne Valadon installed her atelier there in 1898, and again from 1912 until 1926. She lived at 12 rue Cortot with her son Maurice Utrillo and her second husband and manager, the painter André Utter, who was Suzanne Valadon’s first nude model from 1909 until 1914. The poet Pierre Reverdy lived at 12, Rue Cortot. He was the director of the avant-garde journal Nord-Sud, which, in 1917, published the first texts by the surrealist writers Aragon, Breton, Soupault, and Tzara.

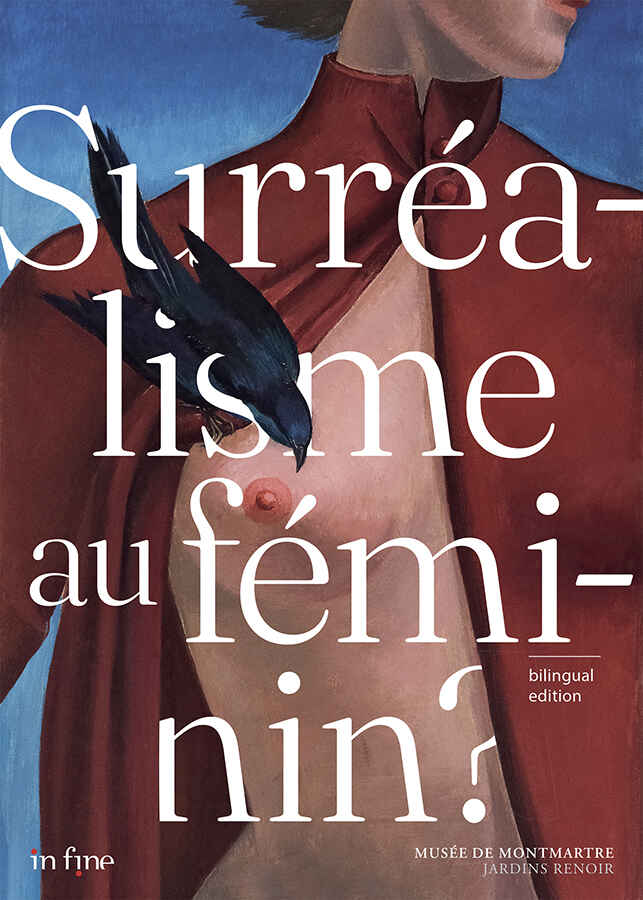

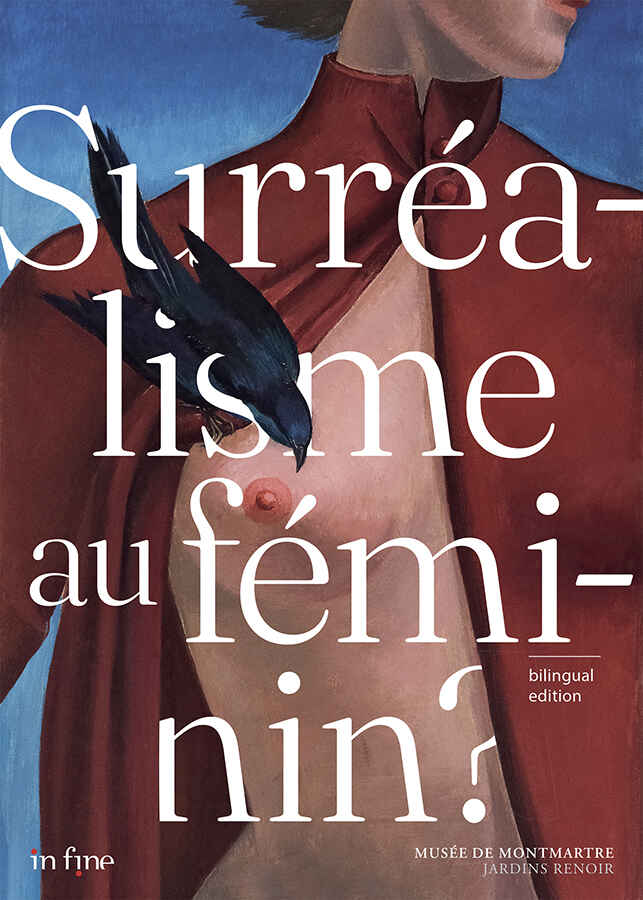

Today, 12 rue Cortot is home to the Musée de Montmartre Jardins Renoir in Paris which, from March 31 until September 10, 2023 shows the exhibition Surréalisme au féminin? You can find the eponymous, bilingual catalogue (French/English) at Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

The exhibition and the catalogue Surréalisme au féminin? explores the unique and enduring contribution by female artists to Surrealism. They lived and worked in Montmartre aka the surrealist hill. Surrealism ‘was neither a system or a school, nor a movement of art or literature, but rather a pure practice of existence’ (Maurice Blanchot, L’Entretien infini, «Le demain joueur», Paris, Gallimard, 1969).

The catalogue and exhibition Surréalisme au féminin? cover not only the history of the surrealist movement—from its birth to its termination in 1969—but also some of its offshoots until the 2000s.

For some of the women artists who joined the surrealist movement in the 1930s—as fervent followers or who were simply involved with the surrealist movement’s founders—Montmartre was a necessary step in their careers.

The catalogue does not mention that, on October 1, 1924 Yvan Goll had published the Manifeste du surréalisme, two weeks before the rival André Breton released his. In their catalogue essay entitled ‘Nobody Will Give You Freedom, You Have to Take It.’, Alix Agret and Dominique Païni mention only André Breton who, on October 15, 1924 set out the (rival) group’s initial principles in his Manifesto of Surrealism.

In their preface of Surréalisme au féminin?, Geneviève Rossillon and Fanny de Lépinau write that, to meet André Breton in 1934, Jacqueline Lamba swam and danced in a water tank, half woman, half siren, every evening at the cabaret Le Coliseum on Rue Rochechouart.

They also mention that, in 1922, André Breton set up his studio at 52, Rue Fontaine. Only a few hundred meters away was Le Cyrano, at 82, Boulevard de Clichy, one of the cafés assiduously frequented by Breton and his friends.

Geneviève Rossillon and Fanny de Lépinau stress that, although the connection between women artists influenced by surrealism and Montmartre fluctuated over the years, the hill district remained an artistic point of reference for them. Affirming their independence often meant moving away—both literally and figuratively—from the Parisian hub under André Breton’s leadership.

According to Geneviève Rossillon and Fanny de Lépinau, these female artists became involved with Surrealism because of its spirit of freedom and revolt, and its framework for expression and creativity that had no equivalent in the other avant-garde movements. They appropriated it, rivalled their male counterparts in creativity, enriched, and ultimately went beyond and prolonged Surrealism after its official dissolution in 1969.

Alix Agret and Dominique Païni write in their catalogue essay (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de) that they chose to exhibit works by roughly fifty female artists, visual artists, photographers and poets from around the world to reflect not only on the ambivalent position occupied by women in Surrealism, but also on its flexibility, the capacity of one of the major twentieth-century movements to integrate women. They study some women often overlooked in the history of art and consider Surrealism in terms of its geographical distribution and peripheral movements, and the distant relationship that women had with it.

In her catalogue essay, Saskia Ooms focuses on the Frenchwomen Claude Cahun and Dora Maar, the American Lee Miller (German article) and the Czech photographer Emila Medková. She underlines that it was not until the 1980s that the first monographs devoted to Cahun, Maar and Miller emerged.

A model for Vogue and an art student, Lee Miller came to Paris in 1929 where she became the assistant, muse and lover of the American photographer Man Ray. In 1947, she became the second wife of the English artist, historian and poet Roland Penrose; they remained married until she died of cancer in 1977.

Saskia Ooms unterlines that the collaboration of Man Ray and Lee Miller contributed to the development of a major technique in surrealist photography: solarisation. Exposing the negative to light before it was completely developed produced objects with troubling and ethereal aureoles.

With Severed Breasts from Radical Surgery in a Place Setting 1 and 2 (1929), photographs of human flesh post-mortem, Lee Miller tackled the subject of strangeness in everyday life and produced a critique on the fragmented female body, often treated as an object by thesurrealist movement. This photograph documents the influence of the assertions and theories of de Sade and Bataille on Lee Miller’s work. According to Saskia Ooms, this pioneering feminist and radical work probably inspired Meret Oppenheim (English article and German article on Meret Oppenheim). She met Man Ray in 1933 and must have seen these images.

Lee Miller had a unique approach to surrealist metaphors, particularly her fragmented female torsos to dissimulate and complexify their female appearance, altered via a form of abstraction or hidden within a phallic form.

Through her collaborationwith Man Ray, Lee Miller joined the surrealist movement, met Max Ernst and acted in Jean Cocteau’sexperimental film Le Sang d’un poète. In February 1932, Lee Miller took part in the exhibition European photography with Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy, at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, and held a solo exhibition there in 1933. At the end of the 1930s, Lee Miller moved to London, contributed with Eileen Agar and Henry Moore to surrealist exhibitions. Saskia Ooms also stresses that Lee Miller created major portraits of the female surrealists in her entourage: Eileen Agar, Nusch Éluard, Dorothea Tanning, Leonora Carrington and Kay Sage.

At the end of her essay, Saskia Ooms mentions Francesca Woodman. Her work followed on from that of these surrealist women photographers, particularly in the transformations and deformations of female nudes—often a mise en scène of her own body—and in oneiric revelations with surrealist motifs (gloves, mirrors, hair) projecting phantasmagorical images.

Alix Agret and Dominique Païni write that a significant number of the women mentioned in their essay would have certainly questioned the principle of this exhibition, condemning the use of the term ‘surrealist’ and/or ‘women artists’. They mention in particular Leonor Fini, Meret Oppenheim and Dorothea Tanning. The latter claimed: ‘Women artists. There is no such thing—or person. It is just as much a contradiction in terms as “man artist” or “elephant artist”. You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you’. Dorothea Tanning also said: ‘I noticed with a certain consternation that the place of woman in Surrealism was no different than her place in bourgeois society in general’.

I hope these few remarks about a show covering some fifty female artists inspire you to visit the exhibition the Musée de Montmartre Jardins Renoir in Paris (until September 10, 2023).

In addition, the catogue offers essays by several authors about British, Belgian, Scandinavian women surrealists, articles about Maya Deren, Mimi Parent, Isabelle Waldberg, Jacqueline Lamba, Surrealism: a ‘Feminist’ Movement? and much more.

Read the bilingual catalogue (French/English) by Alix Agret et al.: Surréalisme au féminin? in fine éditions, April 2023, 176 pages: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Further reading: the bilingual (German/English) book Meret Oppenheim — Mein Album / My Album Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Beauty and Grooming products at Amazon USA

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review of Surréalisme au féminin? are not between quotation marks.

Book review added on April 25, 2023 at 13:42 Paris time.