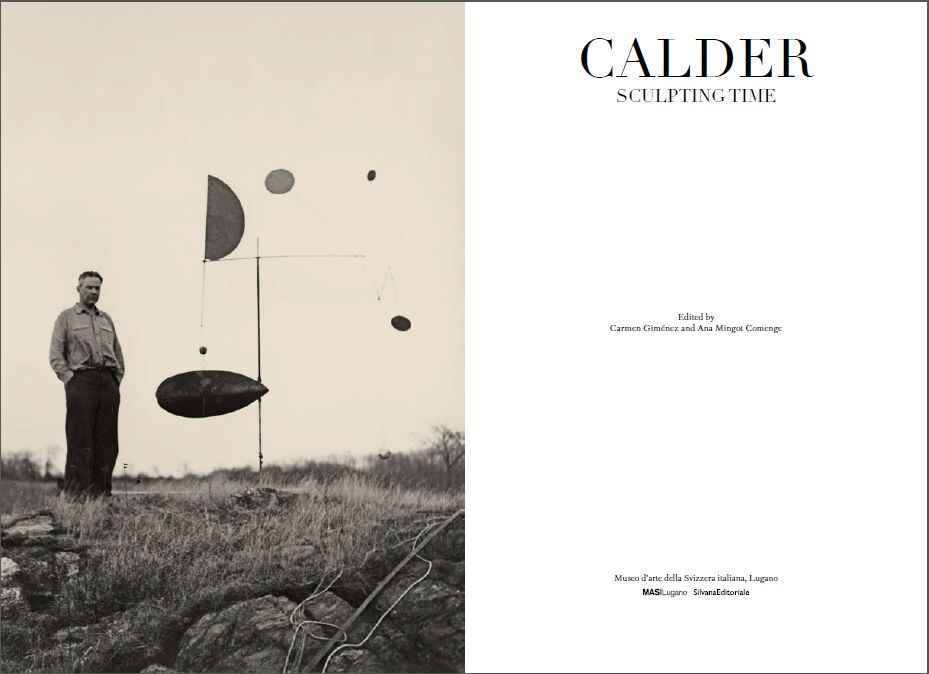

On October 6, 2024 ended the Alexander Calder (1898-1976) exhibition at the Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana (MASI Lugano) in Switzerland. It was largely made possible thanks to the valuable support of the Calder Foundation in New York City. The catalogue remains available. It was edited by Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge.

The exhibition catalogue: Calder: Sculpting Time, edited by Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge, was published by Silvana Editoriale, 2024, 168 pages. ISBN-13: 978-8836657827. Accept cookies—we receive a commission; price unchanged—and order the English version of the MASI exhibition catalogue from Amazon.de, Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk.

In the catalogue, the director of the Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Tobia Bezzola, explains that the MASI exhibition mainly focuses on works executed by the American sculptor Alexander Calder between the 1930s and the 1940s.

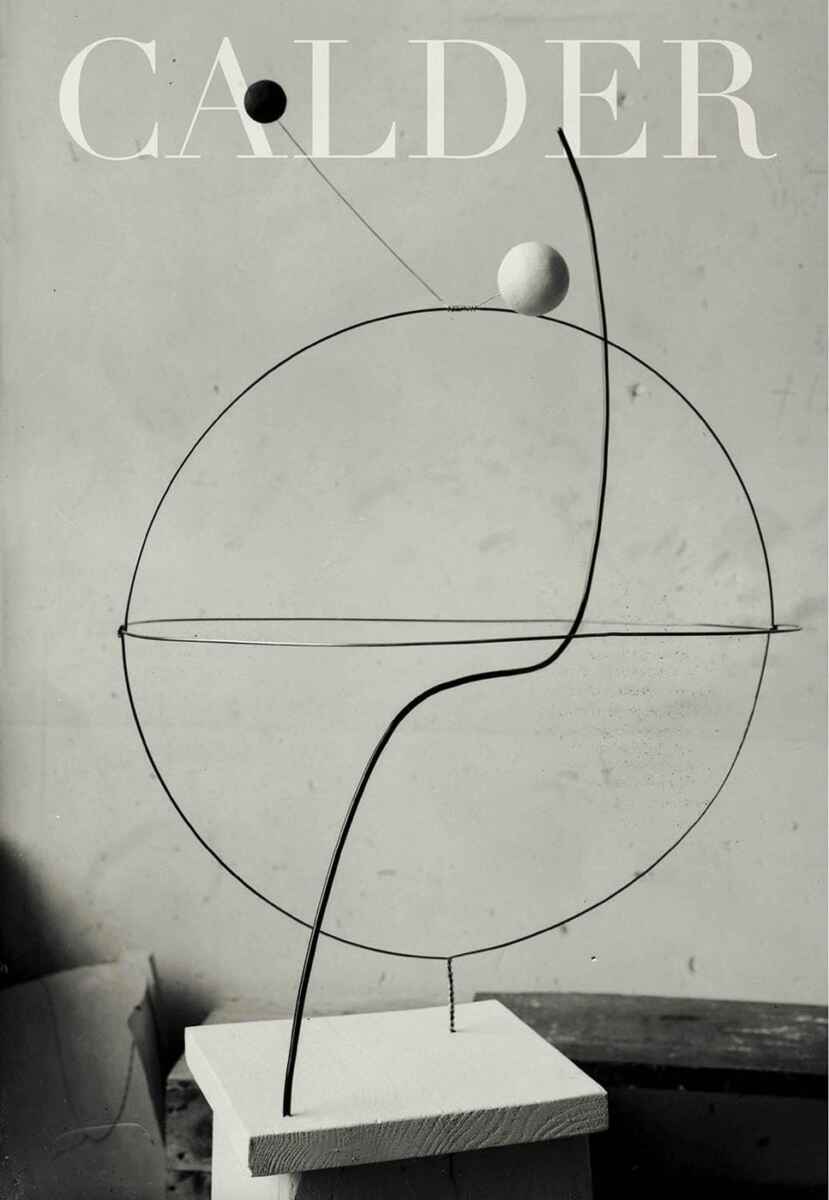

The 35 works on display largely mark the artist’s period of greatest creativity, when he developed a formal and plastic language characterized by unprecedented innovation. According to Tobia Bezzola, from the 1930s onward, with his mobiles Calder introduced the dimension of time into non objective art, managing to capture the essence of movement and balance thanks to his ingenious manipulation of materials and space. Calder plays with the static nature which, by definition, characterizes sculptural forms and, in so doing, invites us constantly to revise our perception of form and dimension.

The curators Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge note that Alexander Calder expended more effort on sculpting than on giving explanations of his art. They describe the artistic art scene the American found in Paris in 1926 at the age of 27 as follows: Cubism and all its formal derivations or imitations were either in decline or had been institutionalized. The International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (Art Déco) had just been held in Paris in 1925, signifying both the apotheosis of fine individualized manufacturing and the swan song of traditional craftsmanship oriented toward contemporary forms.

Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge stress that, since the end of the Great War, the main protagonists of the avant-garde had embraced the “return to order”, also referred to as “classicism”, “neoclassicism”, “noucentisme” or some other similar term denoting a crisis of formalism. Beyond Paris, the movement of De Stijl had arisen in Holland and, after the Soviet Revolution, Suprematism and Constructivism were thriving in Russia, sowing the seeds for what in the interwar period would become Abstraction-Création, the last refuge of formalism.

According to Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge, the most fundamental element of the panorama was Surrealism. It was codified in December 1924 and swept everything else aside by laying the foundations for a new vision. Conceived as it was in literary circles, artistic Surrealism naturally lagged somewhat behind; a delay that proved to be very fertile. It criticizedthe formalism of the avant-garde and reopened the indispensable semantic field. On the other, its anarchic libertinism led to many innovative reprises of Dadaism.

The 1929 stock market crash ended abruptly the folie de vivre of the 1920s. While no longer by any means an aesthetic or technical novice, Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge underline that Alexander Calder was quick to understand what was taking shape artistically in that glittering historical moment. Understanding entails being able to synthesize, and the American artist responded to the time’s restless and fertile circumstances in the only way possible: by expanding his core foundation.

The curators note in the catalogue that Alexander Calder’s post-1926, dprodigious output rested on synthesizing key elements: line, brilliance, gravity, movement. All, of course, interdependent, yet together each element strives toward establishing a distinctive galaxy. Certain works by other artists complement that galaxy. According to our curators, they are few in number—perhaps only two: Pablo Picasso’s Guitar (1912) and Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913). I would add that, in 1936, Meret Oppenheim would add Beyond the Teacup (aka Pelztasse aka Le déjeuner en fourrure.

According to the MASI curators, Alexander Calder intuitively understood the revolutionary value of inventions like Picasso’s and Duchamp’s, establishing a singular aerostatic basis for his own trajectory. They underline that, possessing the genius of curiosity, the American, like great artists of every age and epoch, was never averse to distilling from the finest of visions to make his own stew. He took the most of common ingredients and made them taste differently. According to our curators, Calder, unlike Duchamp in this case, did believe in taste. In addition, he was attentive to the contributions of Surrealism as a vindication of the organic and the telluric, without which it is difficult to penetrate the depths of nature’s physical being.

Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge write that Alexander Calder combined the mechanical or industrial production of his works with elements of traditional sensibility, and with the ludic temperament of revolutionary artistic practices. In this, the American was close to Joan Miró and Hans Arp. Alexander Calder extracted what was most personal to himself while maintaining an affinity for biomorphic forms and accidental relationships.

The curators stress that it took Alexander Calder less than five years to mark out his own terrain, establishing that thermodynamic dimension whereby a sculpture not only moves, but does so without a motor. He took the unique step of creating metal organisms that possess the qualities of lightness and variety, in subtle biomorphic forms which, at the same time, are tough and fragile, dynamic and esthetic, firm and hypersensitive.

Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge write that Alexander Calder’s sculpture shine not only through their structured filaments—excellent transmitters of light—but also through their chromatic petals, which act like tiny, mirrored surfaces to capture and transfix the iridescence of ambient light and capture the spectacle of moments.

Regarding the artist’s legacy, the curators note, among other things, that he is the link between avant-garde abstraction and time-based performance and video art.

This and much more you can discover in the exhibition catalogue: Calder: Sculpting Time, edited by Carmen Giménez and Ana Mingot Comenge. Published by Silvana Editoriale, 2024, 168 pages. ISBN-13: 978-8836657827. Accept cookies—we receive a commission; price unchanged—and order the English version of the MASI exhibition catalogue from Amazon.de, Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk.

Carmen Giménez had previously curated the major Alexander Calder retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. With Calder: Sculpting Time, Carmen Giménez brings to its conclusion her time as President of the Fondazione MASI Lugano.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this Calder: Sculpting Time catalogue and exhibition review have not been put between quotation marks.

This Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana (MASI Lugano) catalogue and exhibition review was added on October 8, 2024 at 20:39 Swiss time.