From September 26, 2025 until January 18, 2026 the LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster is showing the exhibition Kirchner. Picasso. Subsequently, the show will travel to the Kirchner Museum Davos, where it will be on display from February 15 until May 3, 2026. Anna Luisa Walter is responsible for curating the exhibition in Münster, Katharina Beisiegel for curating the Davos show.

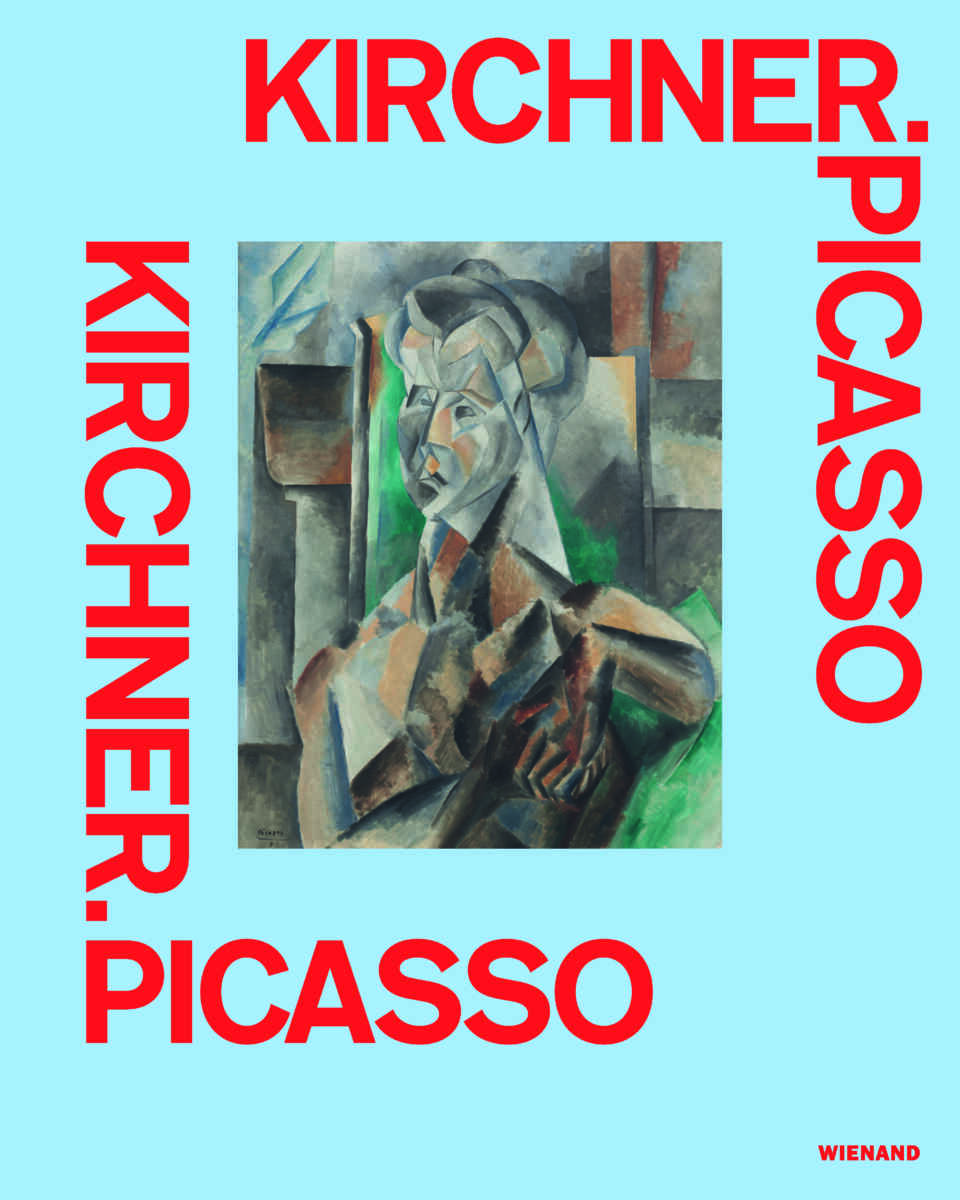

The catalogue, edited by Katharina Beisiegel, director and curator of the Kirchner Museum Davos, and Hermann Arnhold, director of the LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster: Kirchner. Picasso. Wienand Verlag, 2025, 224 pages with 187 color and 15 b/w illustrations, 24 x 30 cm. ISBN 978-3-86832-839-4. With contributions by Katharina Beisiegel, Matthias Gegner, Laurence Madeline, Markus Müller, Anna Luisa Walter. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of the catalogue from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

The German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938; German articles) and the Spanish master Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) are two icons of classical modernism (Klassische Moderne). In Münster and Davos, the two artists are/will be presented side by side, even though they never met in person and, until now, have only ever been studied and exhibited separately.

In the catalogue’s Forword, Katharina Beisiegel and Herman Arnhold underline that the direct confrontation of works by these two leading artists allows a comparative view. Kirchner and Picasso are fundamentally different. Yet, an examination of their output, placing their works in dialogue, reveals – despite all the differences – striking parallels, which are evident in shared sources of inspiration, subject matter and formal aspects, which extend beyond their shared contemporaneity.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s search for new artistic directions – expressed through an interest in the ‘exotic’ and ‘primitive’, in other countries and cultures – runs like a common thread through Kirchner’s life and work. Masks and figures from the German colonies, which had entered European ethnographic museums over the course of the 19th century as exoticised ‘curiosities’ or as ethnographic study material, were recognized by progressive artists, dealers, and collectors as artworks. Kirchner appropriated this visual language, which allowed him to develop original works across a variety of media.

Equally significant were Picasso’s visits to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. He was as deeply impressed by the so-called Africa Gallery as by his discovery of Palaeolithic cave paintings, megaliths, and Venus figurines. He completed the groundbreaking painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon shortly after his visit to the Trocadéro in 1907. Two of the five titular female figures have faces that resemble African masks.

Beisiegel and Arnhold stress that Kirchner’s intense engagement with non-European visual languages made him adopt iconographic elements such as abstracted faces, simplified bodyforms and frontal poses, transforming them into an expressive and unmistakable formal language.

They note that Picasso’s interest in German painting was largely limited to the Old Masters such as Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach the Elder and Matthias Grünewald, whereas the young German avant-garde had already discovered the Spaniards work in the early 20th century. At the legendary Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne in 1912, Kirchner was able to gain his first comprehensive impression of Picasso’s work from the Blue Period to Analytical Cubism through sixteen exhibited paintings. In 1925, Kirchner saw other works by Picasso at the ‘Internationale Kunstausstellung’ in Zurich and, in 1932, he visited the Picasso retrospective at the Kunsthaus Zürich – an event that had a significant impact on what became known as Kirchner’s New Style, according to Beisiegel and Arnhold. Picasso’s surrealist portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter, with sensuous, amorphous bodily forms, inspired some of Kirchner’s pivotal nudes.

According to the two museum directors, through the continuous reworking of their themes, both Picasso and Kirchner produced the largest and most significant bodies of printmaking in modern art, both in terms of quantity and quality.

The Münster and later the Davos exhibition (will) allow visitors to address the connections and contrasts within their respective oeuvres. Together with the catalogue, they examine the sources of inspiration, self-representation and depictions of the ‘other’ and try to answer questions of gender-equitable, colonial historical and current societal perspectives.

The Münster exhibition is structured thematically in line with its conceptual questions. Alongside popular entertainment culture – which played a key role at the beginning of both artists’ careers – it focuses on classical pictorial subjects such as the portrait, and nudes in the studio or in nature. It also explores how Kirchner and Picasso perceived themselves and shaped their public personas, as well as their relationships with their models. With the additional chapter ‘Dialogue of the Avant-Gardes’, the Münster exhibition highlights the broader historical and social context in which Picasso and Kirchner worked, including the artistic exchange between Germany and France.

The Davos show will trace both artists’ development through concentric topic areas – from early Impressionist works to defining turning points in their oeuvres: from Picasso’s Blue Period and Kirchner’s ‘Berlin Street Scenes’ to surrealist portraits and flat, abstracted nudes.

Katharina Beisiegel and Hermann Arnhold conclude that Kirchner’s and Picasso’s acute sensitivity to the upheavals of modernity is evident not only in their paintings and sculptures but also in sketches, drawings, and above all in their style-forming graphic work – from Kirchner’s expressive woodcuts to Picasso’s surrealist etchings.

In the catalogue, Markus Müller writes about the exchange between the French and German avant-gardes as well as “Kirchner’s France Complex” although, as the 1907 Brücke exhibition at the Kunstsalon Emil Richter in Dresden showed, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was considered an original and independent artist without precedent. The German art critic F. Ernst Köhler-Haussen wrote in a newspaper article: ‘I am particularly taken with Kirchner’s originality and independence. His subjects are new and unusual, his means entirely without precedent.’

Markus Müller insists on the importance of the French influence on Kirchner. He writes that, in Wilhelmine Germany, the French avant-garde was received by a relatively small group of collectors, gallerists and museum directors. But they were exceptionally active. Müller mentions people such as Karl Ernst Osthaus, Harry Graf Kessler, Paul Cassirer, Herwarth Walden and Alfred Flechtheim. In Dresden – the principal centre of activity for the young Brücke artists until 1910–1911 – a lively programme of exhibitions at two local galleries helped expose the emerging Expressionists to the work of the French Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and the Fauves associated with Henri Matisse.

Kirchner later downplayed or even denied the French influence, but Markus Müller insists that, as early as 1906/07, the French Fauves and their vibrant, expressive art were introduced to German audiences in a touring exhibition that also made a stop at the Galerie Arnold in Dresden. It was likely that, at that very show, the Brücke artists first encountered works by Henri Matisse, together with paintings by van Gogh, Seurat, and Signac.

In 1909, Max Pechstein and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner saw the Matisse exhibition at Paul Cassirer’s gallery. They wrote to their Expressionist friend Erich Heckel: ‘Matisse partly very wild’. In November of the same year, Pechstein and Kirchner saw paintings by Paul Cézanne at Cassirer’s gallery. On a postcard addressed to Erich Heckel, Kirchner drew a copy of Cézanne’s Seated Man from 1889/90. The sitter’s head posture in Kirchner’s colored drawing differs from that in the original, and the background elements – curtain and chest of drawers – are only summarily outlined. Further evidence of Kirchner’s engagement with Matisse can be found in a postcard illustrated by Kirchner himself, which he and Pechstein sent to Erich Heckel in May 1910. Both had visited the 20th exhibition of the Berlin Secession, and Kirchner had added to the card a sketch after Matisse’s portrait of his daughter Marguerite from the same year, which had been shown in the exhibition.

According to Markus Müller, it is clear that the Brücke artists recognized in the works of the French Fauves an artistic kinship and a shared aesthetic intent. In January 1908, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff wrote to the Swiss artist Cuno Amiet: ‘Dear Amiet, do you know Van Dongen in Paris? We intend to appoint him as a member. We also hope to get H. Matisse and E. Munch on board.’ In 1909, Heckel wrote to Amiet: ‘Do you know Matisse personally? Then it would be best if you invited him – especially since you are more fluent in his language.’

Markus Müller thinks that Kirchner must have perceived his unfamiliarity with the French capital – then regarded as the world capital of the arts – as a shortcoming. His knowledge of the French avant-garde was based entirely on what was shown in German exhibitions.

The art critic Lucius Grisebach wrote that, being influenced by others, remained a lifelong taboo for Kirchner. But in reality, his encounter with the art of Matisse and the Parisian Fauves led to a liberation in the German Expressionist’s handling of color and surface, culminating – again in Grisebach’s words – in a ‘water-color-like, loose painting style with fluid brushwork’.

Kirchner’s notorious efforts to distance himself from the French avant-garde were undoubtedly rooted in his artistic ego, but they must also be viewed within the specific context of contemporary art criticism and its conceptual framework, according to Markus Müller.

Regarding contrasting national schools, Kirchner attributed an intuitive creative principle to German art, and a constructive one to the Romance tradition, writing: ‘The German artist immerses himself in life and imagination, and pure form emerges from this almost without a process of reason; the Romance artist organizes constructively with sharp intellect.’ Markus Müller notes: Yet art critic Meier-Graefe’s developmental model – his concept of the absolute primacy of the French avant-garde – is omnipresent in the minds of the German Expressionists.

Nationalism played an important role during the early 20th century, notably before and during the First World War.

Kirchner expressed scepticism as to whether the art of the German Expressionists was truly appreciated in France, voicing doubts on this point as he believed there to be lingering resentments towards the Germans and their aesthetic: ‘As things still stand today, in my opinion it is too early – and rather harmful – to try to foist our people on the Parisians. We’re just wasting our ammunition and achieving nothing, because the psyche of our artists is too alien there, and our painterly technique still comes across as “trop boche”.’

At the end of his much more detailed catalogue contribution, Markus Müller writes that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner envisioned a Kirchner–Picasso exhibition that would offer the public the ultimate opportunity for direct comparison, with the potential to reveal ‘that P[icasso]creates in an entirely different way and from a completely different mindset’. Kirchner outlined this idea in a letter dated just days before the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, which would bring a sudden and brutal end to creative comparison and dialogue among the international avant-gardes. In Hitler‘s Germany, there was no place for Expressionism or any other work of classical modernism.

In his catalogue contribution, Matthias Gegner focuses on the early-modernist spirit in the works of Kirchner and Picasso. According to him, the two were united by an inexhaustible creative drive and a profound pursuit of artistic truth. He describes Picasso as the tireless innovator who continually pushed the boundaries of art, and Kirchner as the seeker who, from a deeply personal perspective within a restrictive society, strove for an authentic depiction of life. Their works combine radical innovation with the existential questions of modernity. They reflect the social and artistic upheavals of the early 2oth century, writes Matthias Gegner.

These are just a few take-aways from the exhibition catalogue, edited by Katharina Beisiegel, director and curator of the Kirchner Museum Davos, and Hermann Arnhold, director of the LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster: Kirchner. Picasso. Wienand Verlag, 2025, 224 pages with 187 color and 15 b/w illustrations, 24 x 30 cm. ISBN 978-3-86832-839-4. With contributions by Katharina Beisiegel, Matthias Gegner, Laurence Madeline, Markus Müller, Anna Luisa Walter. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the English version of the catalogue from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this review of the Kirchner. Picasso exhibition catalogue are not put between quotation marks.

Review of the Kirchner. Picasso exhibition catalogue added on November 1, 2025 at 20:08 German time.