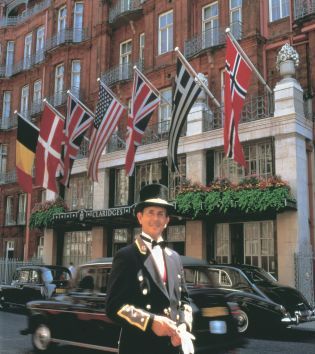

The five-star luxury hotel in Mayfair, London.

The five-star luxury hotel Claridge’s in Mayfair, London, combines traditional English and Art Deco features with excellent service. In its first edition of 1878, Baedeker’s London listed Claridge’s as “The first hotel in London”, and until today, it has remained one of the city’s finest addresses.

The history of Claridge’s begins in the early 19th century. The hotel was first known as Mivart’s. It opened in 1812 in the house at 51 Brook Street. Lord William Beauclerk leased the building from the Grosvenor Estate with permission to turn it into a hotel, which was run by James Edward Mivart. The French chef Jacques Mivart anglicized his first name and, “like his compatriots, Grillion, Escudier and Jacquier, prospered exceedingly, fulfilling the needs of English county families who, half frozen in their draughty homes and suffering from a surfeit of joints, fowls, puddings and port, appreciated the variety and subtlety of French cooking” (Reginald Colby).

Mivart’s was established under royal auspices: the Prince Regent, who succeeded to the throne as King George IV in 1820, had a suite of rooms permanently reserved for him at the hotel in order to discretely enjoy life, for which he – a playboy in today’s vocabulary – was famous.

The hotel was designed for guests who wished to stay for longer periods: apartments were let by the month, rather than by night. Mivart’s success lay in his ability to accommodate foreign royalty and nobility in style while maintaining the ambiance and discretion of a well-maintained private house. In 1827, The Morning Post noted that Mivart’s was the fashionable rendezvous for the high Corps Diplomatique. It soon established the reputation of being “the usual residence of sovereign princes and other foreigners of distinction”. Catherine Gore, the chronicler of the fashionable world wrote in The Diamond and the Pearl: A Novel (1849): “Lord and Lady Downham were perceived at Ems and Kissingen to be surrounded by Highnesses royal and serene and Russian princes sufficient to have peopled Mivart’s Hotel.”

By 1838, James Edward Mivart’s enterprise was flourishing to the point that he had managed to buy five consecutive houses along Brook Street, knocking down the walls to create one large hotel.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 brought an influx of famous visitors, including the Grand Duke Alexander of Russia and King William III of the Netherlands, who both made Mivart’s their home from home. In 1853, a letter in The Times claimed that there were just three fist-class hotels in London, Mivart’s, The Clarendon in Bond Street and Thomas’s in Berkeley Square.

Already in his 70s, James Edward Mivart had retired in 1854 and sold his thriving business to William and Marianne Claridge, who run a separate hotel in 49 Brook Street, Coulson’s. Incidentally, William was a butler before he became a hotel owner. After Mivart’s death, the hotel changed its name to Claridge’s in 1856, adding “late Mivart’s” underneath.

The Claridges owned the entire row of houses in Brook Street from no. 49 to the corner of the block. They maintained the standards set by Mivart. The reputation of Claridge’s continued to grow and to attract famous visitors. In 1860, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert arrived at the hotel to visit the Empress Eugénie of France who was in residence there during the winter. Queen Victoria was so impressed by Claridge’s that she wrote to her uncle, Leopold I, King of the Belgians, in glowing terms of the visit.

In 1881, William Claridge’s failing health forced him and his wife to sell the hotel to a consortium, which lacked the personal touch. Furthermore, consisting of several private houses run together, Claridge’s could not be upgraded to compete with purpose built hotels which were cropping up all over London. For instance The Savoy, built in 1889, offered lifts to all floors, electricity, en suite bathrooms and the best chef in Europe, Auguste Escoffier. In order to compete with the new purpose built luxury hotels, a simple upgrade would not do the job.

Claridge’s Foyer landscape. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

Façade and doorman. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

Art Deco detail: Leaping Stag. Photo © Ken Hayden/

Claridge’s, London.

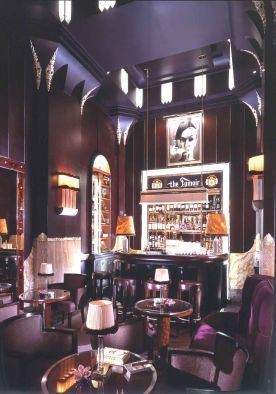

Macanudo Fumoir Bar. It features the largest selection of Macanudo cigars plus more than twenty different Cuban cigars. In addition, a library of rare and exclusively aged cigars has been procured. Claridge’s Macanudo Fumoir serves a carefully edited selection of cognacs, armagnacs, rums, tequilas and ports from its marble horse shoe bar. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

In 1893, on the suggestion of César Ritz, Richard D’Oyly Carte, the founder of The Savoy Group, took over Claridge’s. The Duke of Westminster granted D’Oyly Carte the right to rebuild the hotel with the proviso that he did not repeat The Savoy in Brook Street.

The new owner commissioned the architect C. W. Stephens, famous for rebuilding fashionable areas in West London as well as for the rebuilding of Harrods. Lady de Grey, the leader of London society, laid the foundation stone of the new Claridge’s. The furniture and effects of the old hotel were put up for auction.

Built on the American model, the new hotel incorporated not only many more suites than before with improved plumbing, but also several public apartments on the ground floor, decorated in 1897 by the celebrated interior designer of the day, Sir Ernest George. These rooms were divided by gender with the gentlemen enjoying a smoking and billiard room, the ladies a reading room and drawing room.

The new Claridge’s – now a Grade II Listed Building – reopened in November 1898 with lifts, electric lights and en-suite bathrooms which had made the success of The Savoy. It was so revolutionary that the new management thought it advisable to inform its regular guests that “the spirit of modernism in the nine-storey building would not in the lest interfere with their comfort and privacy” (Reginald Colby).

Richard D’Oyly Carte was not only a hotel owner but also a theatrical producer. He was the impresario of Gilbert & Sullivan’s Savoy Operas. On the Royal Suite’s grand piano, Arthur Sullivan and W. S. Gilbert composed the famous operettas.

In 1909-10 a ballroom was added facing Brooks Mews. It was designed and decorated by French designers in the Louis XV style with reliefs by Marcel Boulanger, paintings in the manner of Watteau and lighting by Baguès. Today, this room is known as The French Salon.

After the First World War, many aristocrats were forced to sell their London houses. Renting a suite at the London Season was much cheaper as the hiring and keeping of staff was no longer needed. Claridge’s became a favorite society venue.

Ernest George’s public rooms must have appeared dated to the fashionable young Mayfair set. Therefore in 1925-26, the Savoy Group hired Basil Ionides, a pioneer of Art Deco design and a specialist in interior decoration, to transform the restaurant. Three years later, the awkward carriage drive was demolished and a new main entrance substituted to designs by Oswald Milne, who also restructured the restaurant and the billiard room for use as a grill room.

Brook Penthouse sitting room. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

The Duke of Westminster offered to sell the freehold of the site to the Savoy Group. In 1930-31, two houses were demolished and a new block was erected next to C. W. Stephen’s “original” Claridge’s. Oswald Milne incorporated private guest rooms and suite of fine reception rooms. The finest British craftsmen of the time worked for the hotel, making it still today the envy of many Art Deco lovers. In 1936 Milne added a small penthouse suite and, in 1962, his assistant Underwood, with the help of Michael Inchbald, added a second penthouse.

Claridge’s was fortunate to escape bombing during the Second World War. In the early 1940s, the Grill Room with its separate entrance on Davies Street became Claridges Causerie. Designed by Sir Howard Robertson, the Causerie served smörgåsbord, and the twist was that clients could eat as much of this as they liked, while only paying for their drinks. This brave novelty was a successful attempt to make rationing seem a little less depressing

Many royal families who found themselves exiled from their own countries as war raged across Europe made their way to the familiar haven that was Claridge’s. The list includes the monarchs of Norway, Greece, Yugoslavia and The Netherlands. The son of exiled King Peter of Yugoslavia, Crown Prince Alexander of Yugoslavia, was born in Suite 212 in July 1945. Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill declared the suite Yugoslav territory for the day and legend has it that a spadeful of Yugoslav earth was sprinkled under the bed so that the heir to the throne could literally be born on Yugoslav soil.

At the end of the Second World War, when unexpectedly defeated in the General election of 1945, Winston Churchill was temporarily without a home and took a suite at Claridge’s.

After the war, State delegations from around the world stayed at Claridge’s. Many of these would be invited to attend a banquet in their honor at Buckingham Palace. Eventually it became traditional for visiting statesmen to return hospitality by hosting a banquet for the Queen at Claridge’s. As a result of this, the Royal Family became familiar with the hotel’s standards of hospitality and service and chose to host many of their own private family parties at the hotel.

King Hassan II visited Claride’s after a stay with the Queen at Buckingham Palace. In the hotel, he found that he could not sleep in the bed that he had brought with him from Morocco. The hotel manager suggested that he should swap beds with his valet, who was sleeping on the handmade Savoy Group bed. The next day, the King raved about the good night’s sleep he had enjoyed and purchased thirty mattresses to take back to Morocco.

In 1999 Claridge’s embarked on the first major designer restoration since the 1930s, when David Collins was invited to create a new cocktail bar. New York-based designer Thierry Despont was brought in to revitalize the Foyer area. Using archive photographs of the Ballroom Extension that dated from the early 1930s as inspiration, the space was completely made over in a modern Art Deco style, with a dramatic Dale Chihuly chandelier as its centerpiece.

Thierry Despont went on to create Gordon Ramsay at Claridge’s, where the celebrated Scottish chef (awarded three stars by Michelin) heads a brigade of thirty-five. The restaurant opened in October 2001 and is a highlight of today’s hotel. In the old restaurant, the first table inside the door was always reserved for the late novelist Dame Barbara Cartland who dined at Claridge’s for fifty years. Her table was always decorated with pink flowers.

Lynne Hunt of Hunt Hamilton Zuch was commissioned to design a health suite on the sixth floor – The Olympus Suite – transforming former staff quarters into a state of the art fitness facility. Hunt was also commissioned to design a series of deluxe bedrooms on the seventh floor. Richmond International designed a series of rooftop private meeting rooms. Interior designer Veere Greeney redesigned the two rooftop apartments with their terraces overlooking Mayfair to the Houses of Parliament beyond. Tessa Kennedy and John Stefanides were each responsible for redesigning forty guest rooms. The hotel interior designers RPW have worked on the guest rooms on the Art Deco side of Claridge’s.

Last but not least let’s not forget a traditional feature of the hotel: Claridge’s offers a special shower experience with water pouring out of an extra-large showerhead like in a tropical torrent. A lot of guests buy the showerheads but are disappointed afterwards because they had not realized that the shower device alone does not give the torrent results, you also need to have your water under high pressure.

Claridge’s deservedly belongs to the group of The Leading Hotels of the World. As Spencer Tracy once said: “Not that I intend to die. But when I do, I don’t want to go to heaven, I want to go to Claridge’s.”

Added on January 1, 2019: Together with Brown’s Hotel, it is one of London’s oldest operating hotels with one of the trade’s most exciting histories.

Sources for this article: Claridge’s and Reginald Colby: Mayfair. A Town Within London, 1966, 189 p.

Art Deco bathroom. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

Art Deco bedroom detail of the very Art Deco Suite 216 – designed by Lady Victoria Weymouth. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

Guy Oliver Business Executive Suite. Photo © Claridge’s, London.

Claridge’s London hotel review added on September 1, 2004