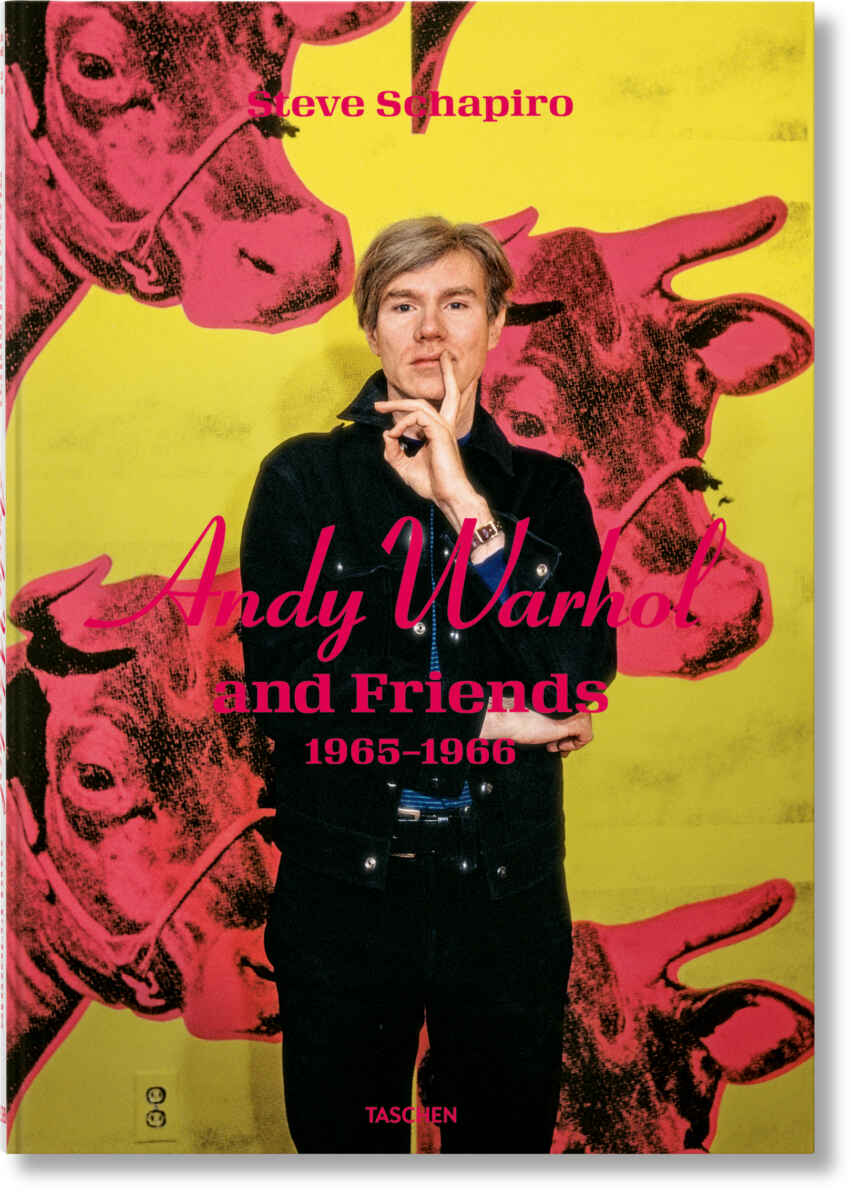

In 1965, the photographer Steve Schapiro (1934-2022), famous for documenting the civil rights mouvement in the 1960s and film stills of classic movies such as The Godfather (1972) and Taxi Driver (1976), started documenting Andy Warhol for LIFE magazine.

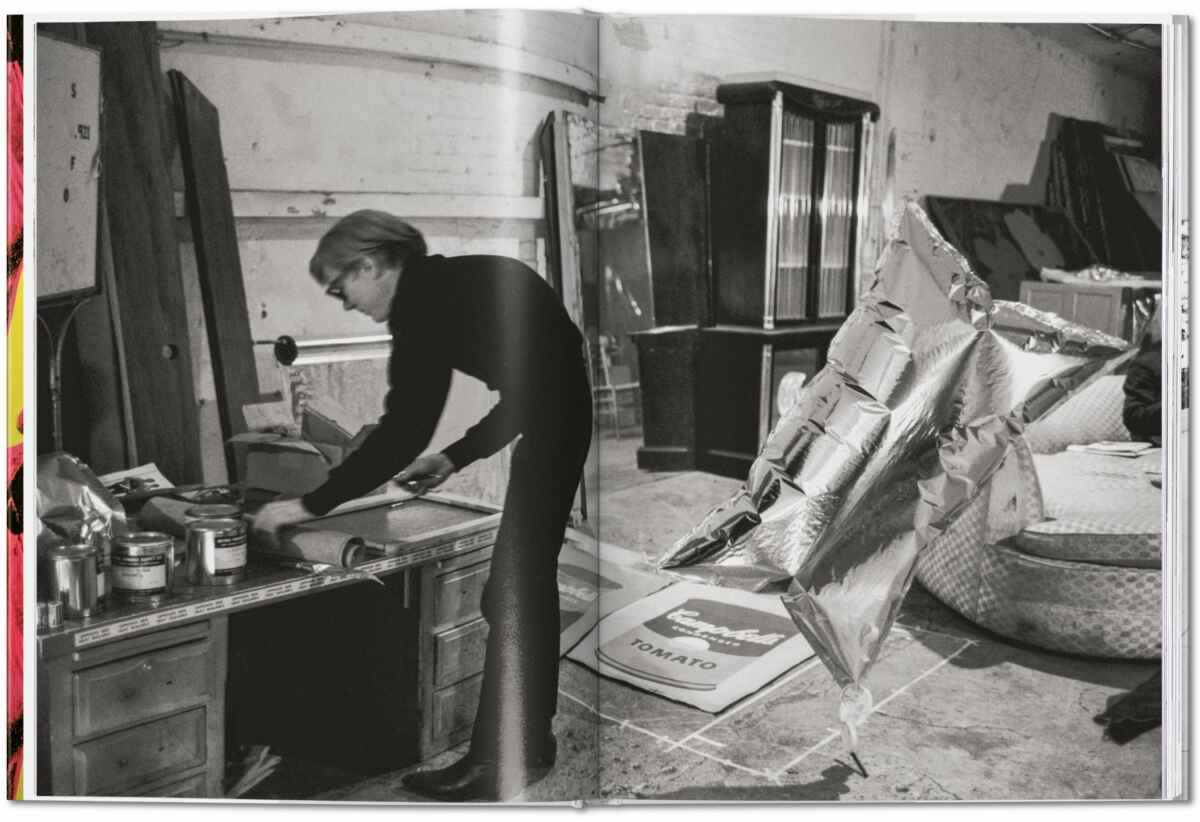

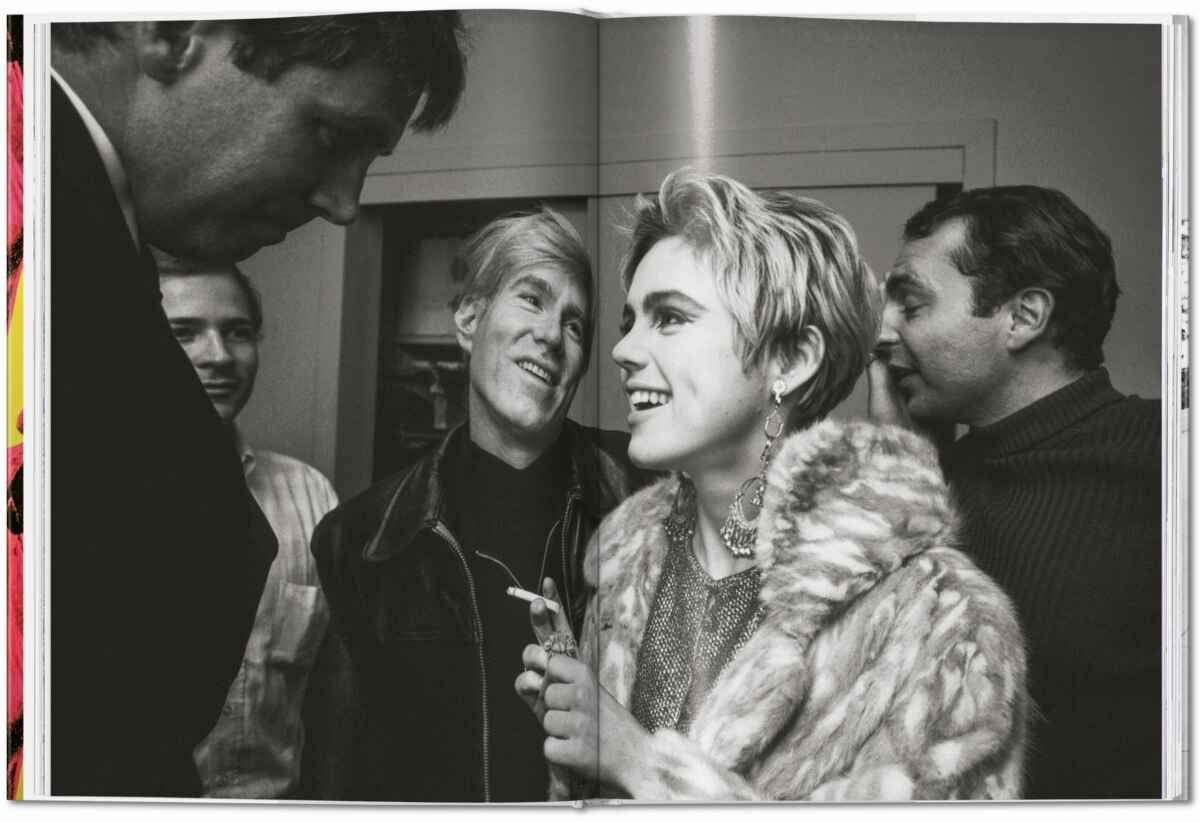

When they met in 1965, Andy Warhol was 37, Steve Schapiro 30. At the time, Andy was cementing a reputation as an important Pop artist who drew his inspiration from popular culture and commercial objects. Steve Schapiro took pictures of Andy and his entourage, including Edie Sedgwick and Nico, hanging out art openings, making his underground movie Camp, working on his silkscreens at the Factory as well as roaming the streets of New York. Steve Schapiro was also present at the opening of Warhol’s first museum retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, attended by a hyped-up crowd of thousands ― where Andymania was born. The last pictures from 1966 were taken in Los Angeles, where Andy exhibited his ironic “Silver Clouds” at the Ferus Gallery, stayed at the picturesque Castle and set up and filmed a performance by the cult band the Velvet Underground.

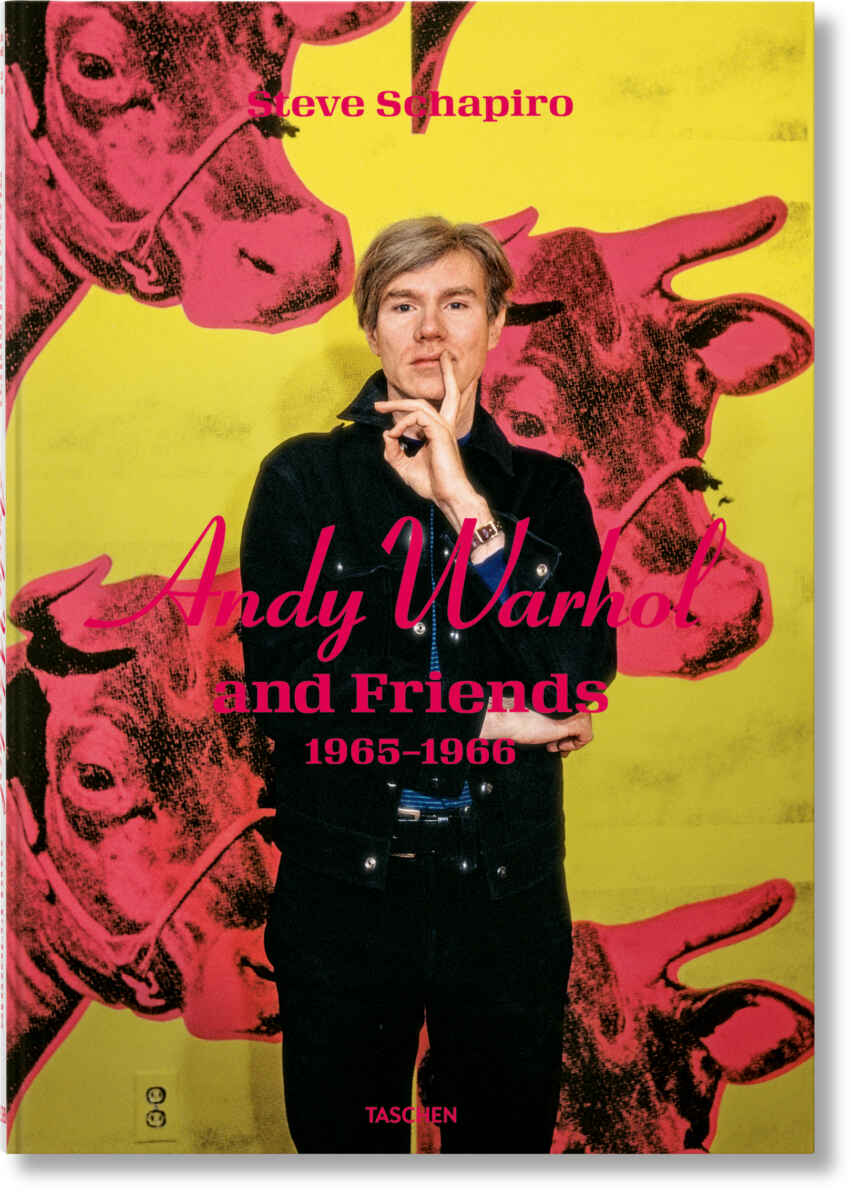

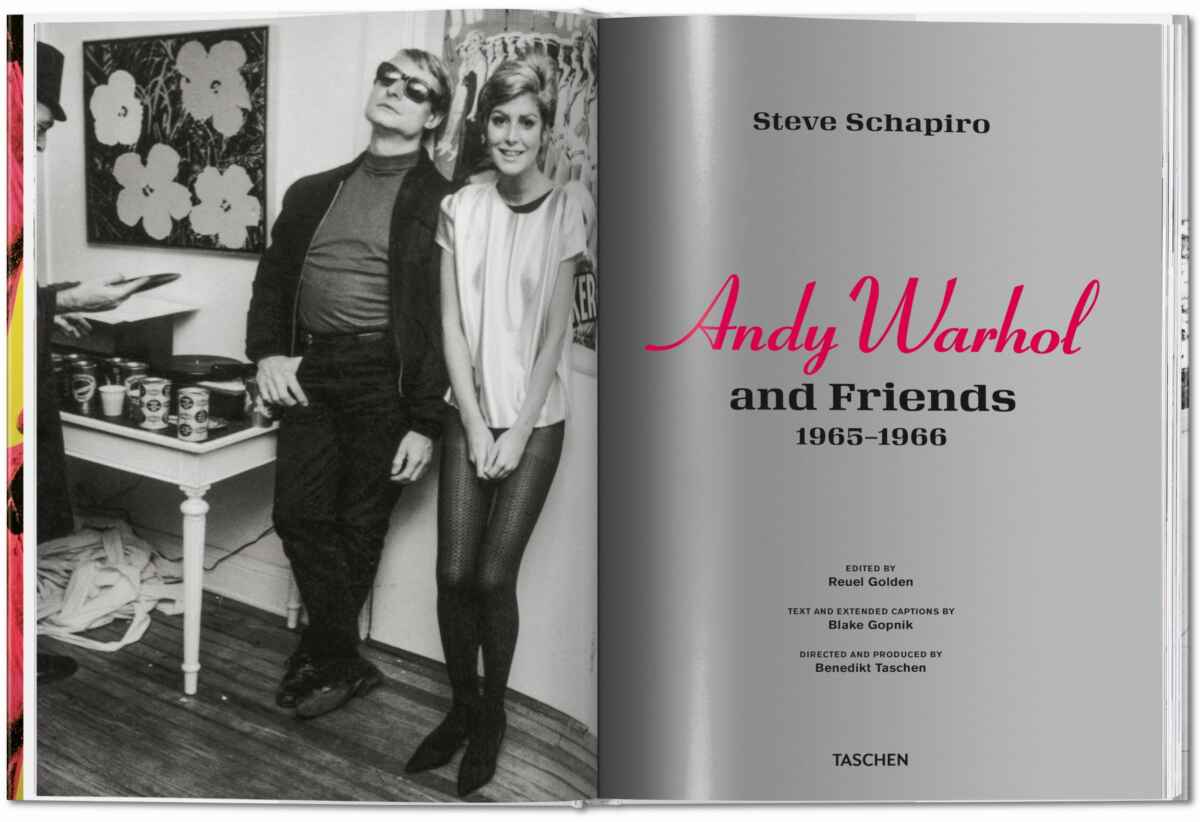

The art and coffee table book Steve Schapiro. Andy Warhol and Friends 1965-1966 features over 120 photographs. Schapiro’s images are juxtaposed with tipped-in plates of original Warhol artworks exhibited during the period. In addition, the book contains an essay and captions by the outstanding Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik (German review of his 1232-page Warhol biography).

Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order Steve Schapiro. Andy Warhol and Friends 1965-1966, Hardcover, TASCHEN Verlag, 23.5 x 33.3 cm, 1.90 kg, 236 pages with over 120 photos, from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Photograph copyright © Steve Schapiro/TASCHEN Verlag.

At the beginning of his essay entitled “Pop Life”, Blake Gopnik notes about this art book: The conception and documentation of Andy Warhol’s greatest masterpiece: “himself.”

Blake Gopnik asserts that, before Warhol, no artist had taken quite his pains to plant a crafted persona deep in popular culture while simultaneously establishing that persona as a credible work of art, inseparable from and on a par with any material objects he might produce and, in fact, more important than some of them.

I would say that, regarding 20th century art, Andy Warhol was and is as influential and as recognizable as Pablo Picasso and his works. In his Warhol biography (accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged: Amazon.de, Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr), Blake Gopnik himself asked: Has Warhol replaced Picasso as the most important and influential artist of the 20th century? And he stated: It looks more and more like it.

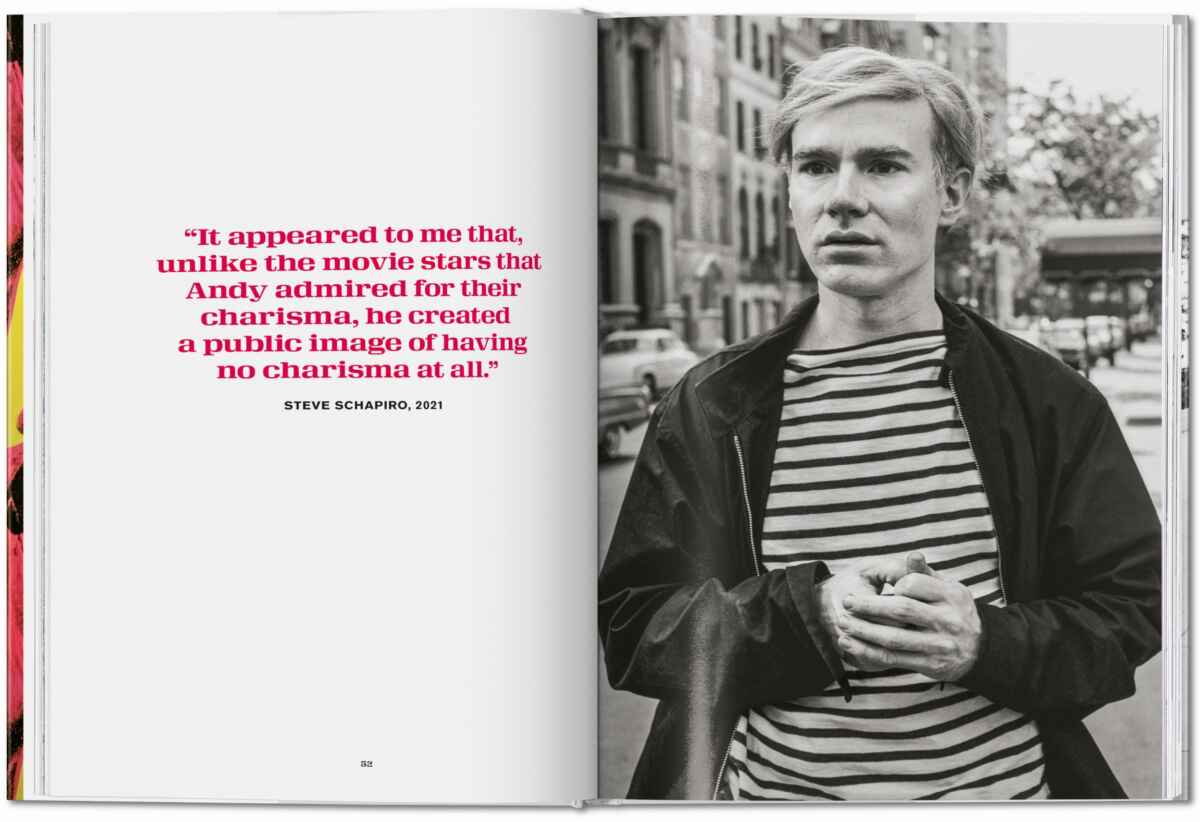

In the Schapiro photo book, the biographer portrays the emerging, groundbreaking artist from Pittsburgh at a transformative period in postwar American culture. Blake Gopnik stresses that the classic Warhol look — shades, leather jacket, mop of white hair — is about as recognizable, and possibly as influential, as Mona Lisa’s smile or the abs on Michelangelo’s David. Andrew Warhola did the shaping of this persona, and the photographer Steve Schapiro helped set it before the world’s eyes.

Photograph copyright © Steve Schapiro/TASCHEN Verlag.

Blake Gopnik underlines that Andy Warhol’s sculpting of a unique creative self got its start two decades before his collaboration with Steve Schapiro. As an art student in Pittsburgh, Andrew Warhola had already painted himself as a little girl in ringlets and as a nude boy-child wearing a girl’s Mary Janes, with the same shock of blond hair that Schapiro caught on film in 1965 and 1966.

According to Blake Gopnik, Warhola got painter friends to depict him with boldly limp wrists and tightly crossed legs — not “manspreading” but “gaytwisting,” as no “real” man in Pittsburgh would ever have sat. In a macho town whose rampant homophobia could prove fatal to its gay sons, the art student went out of his way to establish his presence as the ultimate, effeminate “fairy.” Andy Warhol was a persona that had a recognized place within the Western avant-garde; Jean Cocteau, Warhol’s college hero, was its best-known avatar.

According to the biographer, in New York City in 1949, Warhol seems to have discovered photography as the ultimate tool for his self-presentation. In an early photo by his New York friend George Klauber, a fellow student from Carnegie Institute of Technology, Warhol is captured posing like Greta Garbo, as he he broke into New York’s “window-decorator” crowd (words by Truman Capote). Gopnik underlines that Warhol became one of that crowd’s most successful commercial artists.

In the early 1950s, Andy Warhol got his close friend and fashion photographer Otto Fenn to shoot him wearing a pink suit with a pale camellia in his hand. At that time, both Warhol and Fenn had been obsessed by Greta Garbo as the Lady of the Camellias, in Hollywood’s version of the 1848 romantic novel written by Alexandre Dumas fils.

Photograph copyright © Steve Schapiro/TASCHEN Verlag.

Blake Gopnik stresses that, in the 1950s, in the period before he became a Pop Art celebrity, the Warhol persona seen in those photographs was mostly for private consumption among his friends and familiars. When he presented himself to a larger public, mostly on the “contributors” pages of magazines, he came off as a fairly standard New York creative in a suit and tie — even, sometimes, a bow tie.

The biographer notes that all that barely changed in early 1962 when Warhol’s art first brought him wider fame. During his first two or three years of Pop Art, when the demand for photos of Warhol increased, he looked, if anything, more mainstream than in the ’50s.

In the spring of 1965, Warhol declared that his career as a Pop Art painter was over and that he would be making radical films from then on. He failed to mention another radical project he was embarking on: the creation of a public presence that had some of the same eccentric, countercultural energy as his 1960s paintings and films. Blake Gopnik highlights that is was up to Steve Schapiro to document this change when the photographer’s career was to take off in the fall of 1965 with assignments for publications such as The New York Times and Life magazine.

Photograph copyright © Steve Schapiro/TASCHEN Verlag.

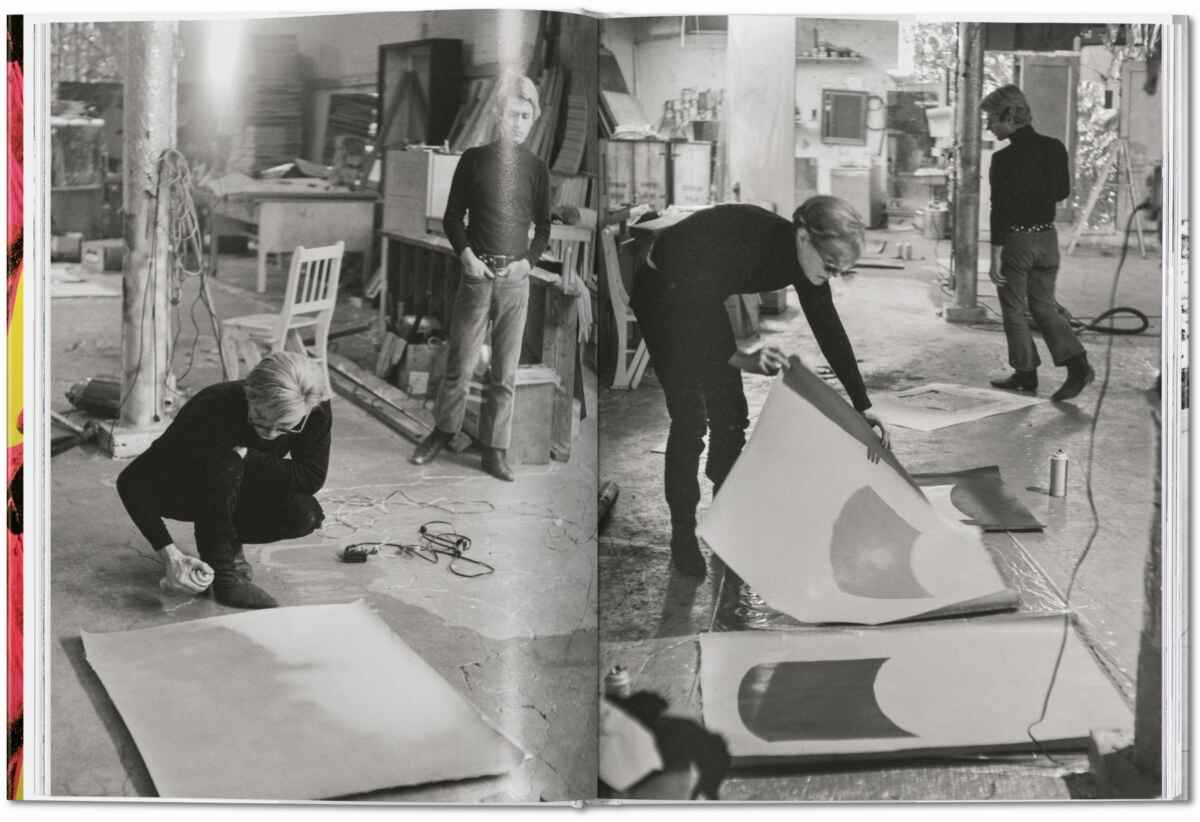

Blake Gopnik notes that, in Schapiro’s early Factory photo sessions, he captured the “real” Warhol: a highly trained, deeply sophisticated and entirely professional artist dedicated to seeding the culture of his era with the most ambitious of avant-garde creations.

When Schapiro came on the scene with his camera, one of the very latest of those creations was “Andy Warhol”, a bizarre human creature who wore sunglasses 24/7 and a biker jacket. At the same time, he perfected his trademark gesture: a hand held to lips in silent perplexity.

Steve Schapiro captured the first public display of Warhol’s new persona on October 8, 1965, when the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia opened the artist’s first museum solo show. Arriving from New York City, he was dressed for motorcycling, a local journalist noted: wrap around sunglasses, blackjeans, and a black bomber jacket with a slew of proto-punk safety pins stuck into its collar. Blake Gopnik stresses that this made Warhol stand out like crazy from the collegians and art-world types who had gathered to receive him that night, most of whom wore ties or button-downs that Warhol himself had been wearing until not long before.

Photograph copyright © Steve Schapiro/TASCHEN Verlag.

By early 1966, under the influence of the four members of the Velvet Underground, according to Blake Gopnik the most aggressive, transgressive, vein-jabbing, hard-charging rock group to hit New York until then, Andy Warhol was adjusting his persona to be far tougher than it had been.

Blake Gopnik notes that Andy Warhol was almost certainly unable to ride a motorcycle; his one attempt at learning to drive had ended years before, after he sideswiped a yellow cab.

On July 9, 1962 Andy Warhol had opened an exhibition at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles with Campbell’s Soup Cans. This marked his West Coast debut of pop art. Back in L.A in 1966, Warhol was deliberately putting more than one version of himself on display. According to Blake Gopnik, the goal must have been to make the constructedness of his persona all the more evident. If his persona was truly going to function as a sophisticated work of artistic “fakery”, rather than as his natural, “naïve” way of being, Warhol needed his photographer to document the artifice involved as well as the total control the artist had over this performance of self.

This and much more, notably great photographs, you can discover in Steve Schapiro. Andy Warhol and Friends 1965-1966. Hardcover, TASCHEN Verlag, 23.5 x 33.3 cm, 1.90 kg, 236 pages with over 120 photos. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order this book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Read also the German article about Leo Castelli, who for instance showed Andy Warhol’s Flowers series in 1964, and the German article about Henri Cartier-Bresson, the French photographer who was a role model for the young Steve Schapiro.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review of Steve Schapiro. Andy Warhol and Friends 1965-1966 have not been put between quotation marks.

Steve Schapiro. Andy Warhol and Friends 1965-1966 book review added on February 4, 2025 at 10:57 German time.