Biography and exhibition at Neue Galerie in New York

The Vienna Secession movement and of course the famous Wiener Werkstätte, co-founded with Josef Hoffmann, are unthinkable without Koloman Moser (1868-1918).

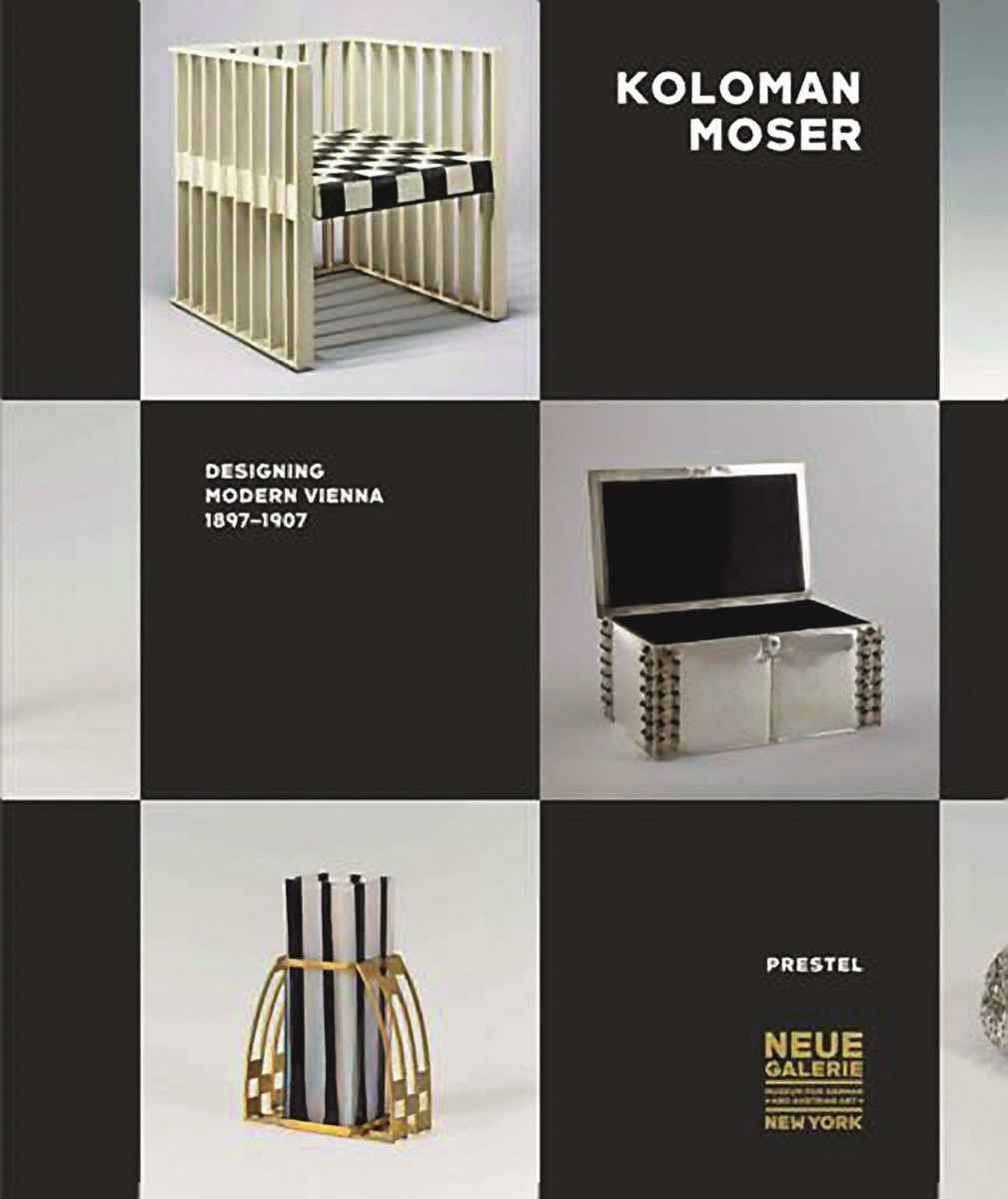

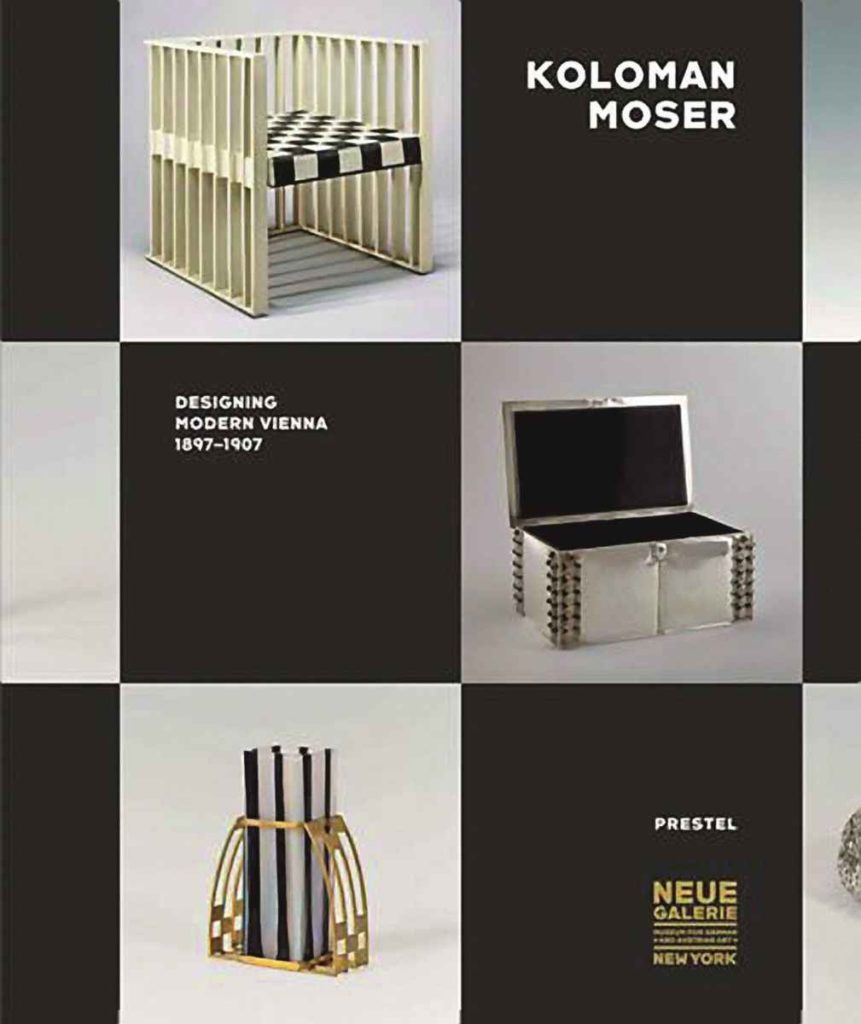

He was multitalented man who excelled at making furniture, stained-glass windows, wallpaper, carpets, interior design, architecture, lighting, silver tableware, ceramics, glass, textiles, couture, costumes, jewelry, posters, banknotes, postage stamps and other graphic design as well as paintings, to which he devoted most of his time in later years.

Richard Wagner had put forward the concept of the opera as a Gesamtkunstwerk. In a similar spirit, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser envisioned arts, crafts and design as an all-embracing total work of art.

The Koloman Moser exhibition at Neue Galerie in New York City (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de) focuses exclusively on his influence in the field of applied arts and interior design. The curator, Christian Witt-Dörring, is considered one of the leading experts for Vienna around 1900. At Neue Galerie, he has already organized the exhibitions “Dagobert Peche and the Wiener Werkstätte” in 2002, “Viennese Silver: Modern Design 1780-1918” in 2003 as well as “Josef Hoffmann: Interiors 1902-1913” in 2006.

In 1897 Koloman Moser had been a founding member of the Vienna Secession, together with Gustav Klimt, Josef Maria Olbrich and Josef Hoffmann. Like the Arts and Crafts movement in the UK under the guidance of William Morris, Hoffmann, Moser and Olbrich saw no difference between high (fine) arts and low (applied) arts. Everyday objects deserved the attention of art works.

Unlike Hoffmann and Olbrich, who were trained architects, Moser had been educated as a painter at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste) and at the School of Applied Arts of the Austrian Museum for Art and Industry (Kunstgewerbeschule des Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie) from 1886 to 1895.

Therefore, his first works were in the media of painting and graphic arts. Under the influence of Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser moved from historicism to a more planar-linear style, as Christian Witt-Dörring explains in the catalogue’s introduction. He developed an autonomous style, a concept for modern ornament, which would later provoke Adolf Loos’s sharp criticism of the Viennese Secession movement of which Koloman Moser had been a leading member until he and Josef Hoffmann founded the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903. In addition, Koloman Moser was an important voice in the Secession’s influential art journal Ver Sacrum.

In 1898 Koloman Moser realized the first mature examples of his early planar art for the façade of the new building for the Viennese Secession as well as for the building as a whole. It was a true Gesamtkunstwerk.

His first works in the field of the applied arts were designs for fabrics and carpets that were manufactured at the Backhausen company.

The Secession was more than just Koloman Moser’s artistic homeland; its members and patrons provided key friendships for life. From Vienna’s upper-middle-class, he also recruited many of his clients. He was himself a lower-middle-class son, his father being a teacher at a preparatory school.

However, in 1905 Koloman Moser married Editha Mautner von Markhof, the daughter of a brewery owner and initially one of his students at the School of Applied Arts, where he had been appointed professor in 1899 together with Josef Hoffmann.

The traditional curriculum insisted on historicism – basing the students’ education on copying historical models. Moser and Hoffmann however insisted on practical training of their students in workshops specific to a material, as Christian Witt-Dörring points out.

One of the first workshops set up was the one for pottery, which produced some of the most innovative works of the new Viennese ceramics. Koloman Moser was most probably inspired to create this workshop by a trip he had made in 1899 to the Technical School for the Ceramics Industry in Znaim (now Znojmo).

After his appointment to the School of Applied Arts, Koloman Moser had devoted most of his time to the design of three-dimensional objects in glass and ceramics as well as furniture. Without the teachings of Hoffmann and Moser, the new Viennese style would not have achieved the rapid spread and acceptance it did all around the Austrian-Hungarian empire.

The name of Koloman Moser is most closely associated with the Wiener Werkstätte, which he co-founded with Josef Hoffmann in 1903 with the help of the textile industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer, who was an unreserved admirer of the Secession.

The Wiener Werkstätte was a productive cooperative of applied artists who realized their ideas of a total work of art. Unlike the art schools, the Wiener Werkstätte was integrated into actual economic life. The artists executed their designs in an unmediated way, in direct contact with the artisans and their clients, in a protected creative and experimental atmosphere, as Christian Witt-Dörring points out.

In the first years of existence, the Wiener Werkstätte produced extremely geometric and abstract formal designs. As at the Secession, Koloman Moser was responsible for the graphic look of the company and designed both the trademark and the monogram of the Wiener Werkstätte.

In 1905, two years after the founding of the new company, Hoffmann and Moser resigned from the Secession. They were no longer in support of the naturalistic tendencies of the majority of the Secession members. In return, Hoffmann and Moser found no support for their idea of Gesamtkunswerk. As a result, the Secession lost its leading role in the Viennese art scene.

In 1907 Koloman Moser left the Wiener Werkstätte and dedicated himself almost exclusively to painting.

Since three institutions were crucial in the artistic life of Koloman Moser, the Neue Galerie exhibiton in New York is divided into three exhibition spaces which show each a specific period in Koloman Moser’s artistic development, connected with different tasks and opportunities.

Initially influenced by the French and Belgian Art Nouveau as well as by the British Arts and Crafts movement, he later developed his own version of curvilinear Viennese planar art. At the School of Applied Arts he began to disseminate an autonomous, modern Viennese style. His formal idiom was transformed under the influence of the works of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, moving from a curvilinear form of expression to a geometric, abstract one. According to Christian Witt-Dörring, within the framework of the Wiener Werkstätte, Koloman Moser produced his most radical and mature works of geometric abstraction.

Koloman Moser was a heavy smoker and diagnosed with incurable cancer of the larynx in 1916. He died on October 18, 1918 in Vienna, where he had been born some 50 years earlier on March 30, 1868.

For more biographical details check pages 348 to 371 of the exhibition catalogue. Both the catalogue and the New York exhibition are a must for any art lover.

This article is based on the catalogue of the Neue Galerie exhibition in New York City: Koloman Moser: Designing Modern Vienna 1897-1907. Prestel, 2013, 399 pages, 400 photographs. Order the hardcover book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de. The exhibition at Neue Galerie in New York City is on display until September 2, 2013.

More books about Koloman Moser available at Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de.