The exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London until February 25, 2007

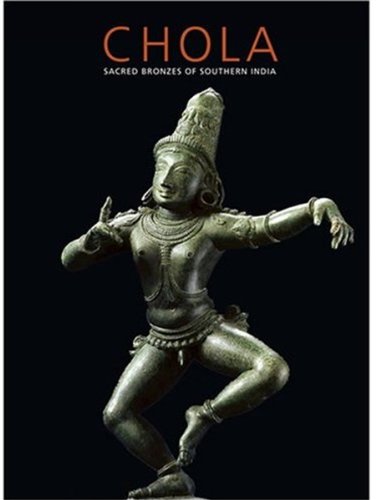

The international exhibition Chola: Sacred Bronzes of Southern India at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (catalogue: Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de) presents until February 25, 2007 some 30 sculptures. For more information on the history of the Cholas, a dynastic group that emerged in the ninth century after the capture of Thanjavur (located in the present day state of Tamil Nadu) in 850 AD and went on to rule until 1250 AD, check the article Chola bronzes about the 2003 American exhibition The Sensuous and the Sacred. Chola Bronzes from South India.

The Pallava period (c. 600-850/900) was marked by a rapid expansion in temple building in south India. The finest temples, built under Royal patronage, are the Kailashnatah (early 8th c.) and Vaikuntaperumal (c. 775) in Kanchipuram as well as the Shore Temple at Mamallapuram, located in the Pallava kingdom’s capital. According to John Guy, these temples, with their deep porches, dark interiors and constricting enclosure walls, mark the transition from cave shrines and rock-cut temples to the beginnings of the mature free-standing Dravidian-style temple.

From around the middle of the first millennium, the god and goddess envisioned as assuming an active role similar to that of the human monarch, participating in a variety of activities. Thus, the devine couple inspected their temple premises each day. The immovable stones image installed in the sanctum could not participate in such festivities. Thus arose the portable Chola bronzes. Along its pedestal, each image either has its set of holes or a set of lugs for the insertion of bamboo poles that would rest on the shoulders of devotees.

John Guy explains that, in South India, portable icons of the gods came into existence to allow the parading of the deity away from the temple sanctuary for both the god’s pleasure and the spiritual benefit of devotees.

Poet-saints made the present day state of Tamil Nadu a sacred landscape of living Hinduism in their winning battle against Buddhism and Jainism. The poet-saints traveled from one temple to the next, propagating and proselytising. More than half of the temples named (‘sung’) by these saints were in Tanjavur district, a Pallava and Chola heartland along the Kaveri river and its delta.

Dating of the icons is delicate. The rising popularity of metal processional images in both Hindu and Buddhist devotional activity begins in the seventh century. However, the first securely dated icon comes from the beginning of the tenth century. This is a figure of Uma as Consort of Nataraja, installed at the temple of Karaiviram village, which, according to its inscription, was consecrated in the eleventh regnal year of Parantaka I, 917 CE. (Incidentally, Uma is the mother aspect of Parvati, the wife of Shiva, and the preferred term for this goddess in south India).

Only few Chola bronzes bear inscribed dates; far more common is the recording of an important donation in a temple description, usually carved into the exterior wall of the temple’s sanctuary.

The tenth, eleventh and twelfth century proved to be periods of great prosperity of the Chola dynasty. Much of the surplus was spent on new and bigger temples and on equipping them with devotional icons and associated ritual paraphernalia.

Stylistically, the processional icons of these periods are of a high standard of elegance. They combine a sensuous naturalism with an unprecedented refinement of gesture and posture. According to John Guy, ornamentation in the form of finely detailed belts, necklaces, armbands and diadems may reflect courtly adornment of the period.

Generally, each festival demanded a specific image, which was not viewed by devotees because the bronzes emerged in precession after the rite of puja in which they were ritually bathed, swathed in silks, adorned with jewelry of gold and precious stones, and honored with blossoms and flower garlands. At times, barely an inch of bronze is clearly visible, but for the devotee, the image adorned is the potent image.

From the reign of Rajaraja through that of Kulottunga I, a series of high-Chola-style bronzes survive, reflecting stylistic shifts and the grades of quality created by the master craftsmen.

By the second half of the thirteenth century, by which stage the Chola dynasty was in decline, the icons’ luminous humanity of the high Chola style had given way to convention.

In the 14th century, the Muslims invaded Tamil Nadu. Stone images were more often vandalized, whereas bronze icons were stole for their considerable metal value. Therefore, many religious bronze sculptures were buried. Today’s finest Chola bronzes were recovered from caches of images secreted away in temple grounds and sometimes in the surrounding countryside.

The Government Museum in Chennai owns the largest collection of south Indian bronze sculptures, mostly acquired directly from temples or through excavation. In 1979 some 78 bronzes, mostly Chola and none later than early 14th century, were discovered concealed in a hidden chamber within the Chidambaram temple. This is the largest collection intact collection of Chola bronzes to have survived from a single temple.

Chola bronzes are unique images that cannot be replicated because of the lost wax (cire perdue) process used to create them requires that the mold be broken open to releases the statue.

The London exhibition focuses on bronze images of the Hindu deities created for the festival cycles of the many Tamil temples. In addition, Jainism and Buddhism also attracted a following during the Chola period. both faiths commissioned portable bronzes of their lord, the Jina or the Buddha, for ritual worship.

The exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts in London. Get the catalogue, Thames & Hudson, 2006, 176 p., 120 ill., from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de.

Further reading / Related articles: History of the Chola empire. Chola bronzes.