Biography of the cellist and her recordings

The British cellist Jacqueline “Jackie” du Pré (* Oxford, January 26, 1945; † London, October 19, 1987) remains in the hearts of classical music lovers around the globe, not just because of her early and tragic death due to multiple sclerosis, but mainly because she had something to say with her cello. She played from the stomach and the heart, through her natural instincts, giving the impression that she created the music in the moment she played it. She touched and moved people instantly.

She was born into a middle-class family in which music played an important role. Her mother both played and taught the piano. The French-sounding name derived from her father’s Channel Islands ancestry.

In 1969, the shy Jacqueline du Pré who had problems socializing told the journalist Maureen Cleave that she was one of those children other children couldn’t stand. She had always felt that in the cello she had some gorgeous secret which she guarded jealously. She said that she was shy except when she played the cello. Then it never bothered her what happened.

Just before her fifth birthday, Jacqueline du Pré heard the sound of a cello on the radio and the course of her life was set. After early cello lessons with Mrs. Garfield Howe, she studied at Herbert Walenn’s Violoncello School in London. At 10, she became a pupil of William Pleeth, who had himself studied with Julius Klengel. Pleeth was a passionate, uninhibited performer. He was best known as a chamber musician. Later, Jacqueline du Pré studied with the greatest cellists of her time, with Pablo Casals in Switzerland, with Paul Tortelier in Paris and with Mstislav Rostropovich in Moscow. However, she always acknowledged Pleeth as her main teacher; she affectionately referred to him as her “cello daddy”. And listening to her style of play, one can easily understand why Pleeth was close to her heart.

In his book Grosse Cellisten, the classical music critic Harald Eggebrecht entitled his chapter dedicated to Jacqueline du Pré “Intensity and Exaltation”. When she played, she gave everything, lived the moment. Her spontaneous, soulful style included exaggerations and distortions, even violence, Eggebrecht writes.

In 1956, Jacqueline du Pré won the Suggia Award, which commemorated the Portuguese female cellist who had died six years earlier. In 1961, aged 16, she made her sensational London Wigmore Hall recital debut, playing a 1672 Stradivari cello. In addition, she started attending the summer school organized by the Argentine violinist and conductor Alberto Lysy.

In 1962 she appeared with a full orchestra for the first time and made her Promenade Concert debut — both times playing Edward Elgar’s late Cello Concerto (Elgar sheet music). Her warm, sad, fiery and ecstatic rendition enchanted both the critics as well as the general public. Subsequently, she began to record for EMI. She almost became the incarnation of Elgar’s Cello Concerto, notably playing it every year at the Henry Wood Promenade Concertos. In an interview, she said about her free interpretation of Elgar that he himself took wild liberties with his own writing. Therefore, she felt completely free to do whatever she wanted.

Jacquelin du Pré formed a sonata duo with the English pianist, harpsichordist, conductor and composer George Malcolm. In 1964, she created another, very successful duo with the American pianist and conductor Stephen Kovacevich with whom she notably toured Britain. In addition, she acquired the 1712 “Davidoff” Stradivarius. By 1965, the shy Jackie was already a star when she made her American debut.

Jacqueline du Pré had a major musical relationship with the pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim, whom she married in 1967 after converting to Judaism.

Artur Rubinstein attended Barenboim’s concerts whenever he could – in New York, and in Paris in the early 1960s. He always invited Daniel to his house afterwards. In 1966, Rubinstein bought a house in Marbella and invited Barenboim there. The young pianist had to decline because in August and September he was at the Edinburgh Festival and later he was ill with glandular fever. This is how Barenboim met his later wife Jacqueline du Pré who had the same illness very badly. The two started talking on the phone, comparing notes. A few months later, Rubinstein was in Portugal where he heard Jacqueline’s first recording. He invited Barenboim and du Pré – they were married by that time – to his house in Spain where they played for him on “innumerable occasions.”

The circle of friends of Daniel Barenboim and Jacqueline du Pré included Vladimir Ashkenazy, Lawrence Foster, Zubin Mehta, Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zukerman.

In July 1971, when Jacqueline du Pré should have been at her peak, she began suffering seriously from a mysterious ailment which affected her playing. Eventually, multiple sclerosis was diagnosed. After a serious of remissions and relapses typical for ms, she retired in 1973, barely 28 years of age! After the performance of the Brahms Double Concerto with Pinchas Zukerman, she was barely able of returning her cello to its case. Despite some teachings and occasional appearances in public, she was never able to play the cello again. Her health deteriorated gradually and she died in London on October 19, 1987. Her husband, Daniel Barenboim, had started a new relationship during her lifetime.

According to Eggebrecht, after Jacqueline du Pré’s death, Lynn Harrell bought one of her two Stradivari cellos. The other one ended up in the hands of the talented Yo-Yo Ma, just ten years younger than Jacqueline du Pré.

Late in 2017, Warner Classics re-issued some of Jacqueline du Pré’s recordings. At the end of 1894, Antonín Dvořák (Dvorak sheet music) started writing his Cello Concerto in B minor for his friend Hanus Wihan. However, through a misunderstanding, it was not Wihan but the English cellist Leo Sturn who played the solo part in the London premiere, with Dvořák conducting. The Bohemian composer was inspired by the rendition of his Second Concerto by his Irish friend, the cellist and fellow composer Victor Herbert, who played it in New York in 1894 alongside three trombones without being drowned; it was all a question of the alternating solo and tutti passages in the right way. A spiritual influence on his Cello Concerto in B minor was his beloved sister-in-law, Josefa Cermakova, whom he had wanted to marry before he settled for her younger sister Anna. Josefa suffered from a heart condition which worsened while Dvorak was in New York. Her favorite among Dvorak’s songs was “Leave Me Alone”. Therefore, he wrote the song’s melody into the Adagio of his Cello Concerto in B minor. Not long after his return to Prague in 1895, Josefa died and the composer inserted a reminiscence of “Leave Me Alone” into the coda of the finale. This was of course an ideal composition to be played be the emotional Jackie du Pré. — Dvorak Cello Concerto in B Minor & “Silent Woods”, Adagio for Cell & Orchestra (Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr).

Jackie du Pré’s two 1968 recordings of the Schumann and Saint-Saëns Cello Concertos with the New Philharmonia Orchestra under the direction of Daniel Barenboim have the kind of spontaneous freedom of line that made her Elgar interpretations such a success. In addition, the slow movements of the compositions were matched by her romantic flair. According to the booklet, the Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor is her greatest studio achievement. As for the Saint-Saëns piece, she had discussed it with Pablo Casals, who had performed it together with the composer himself. In addition, Jacqueline du Pré had chosen to play it at the final concert of Casals master classes she attended in Zermatt in 1960. Although largely identified with Elgar, Jackie repeatedly stated that she loved the Schuman concerto just as much. She first play it in public in London on December 2, 1962. She also played it during her studies with Tortelier at the Paris Conservatoire. In addition, Schumann was at the center of her studies with Rostropovich at the Moscow Conservatory who, in 1966, exclaimed: “This is the most perfect Schumann I have ever heard”. She played the Schumann concerto with Leonard Bernstsein in New York, with Seiji Ozawa in Berlin and with Daniel Barenboim in Tel Aviv. She first recorded Schumann at Abbey Road in April 1968 but, unhappy with the result, another session took place on May 11, 1968. And, this time, the alchemy worked and she fully approved the recording. As for Saint-Saëns, like the Schumann concerto, it is formally unconventional. The composer told Casals that it was inspired by Beethoven’s 6th, largely known as the Pastoral Symphony. Her rendition puts emphasis on the lyrical passages. She keeps the faster ones poised and buoyant, as Tully Potter puts it. — Cello Concerto in A minor. Saint-Saëns: Cello Concerto (Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr).

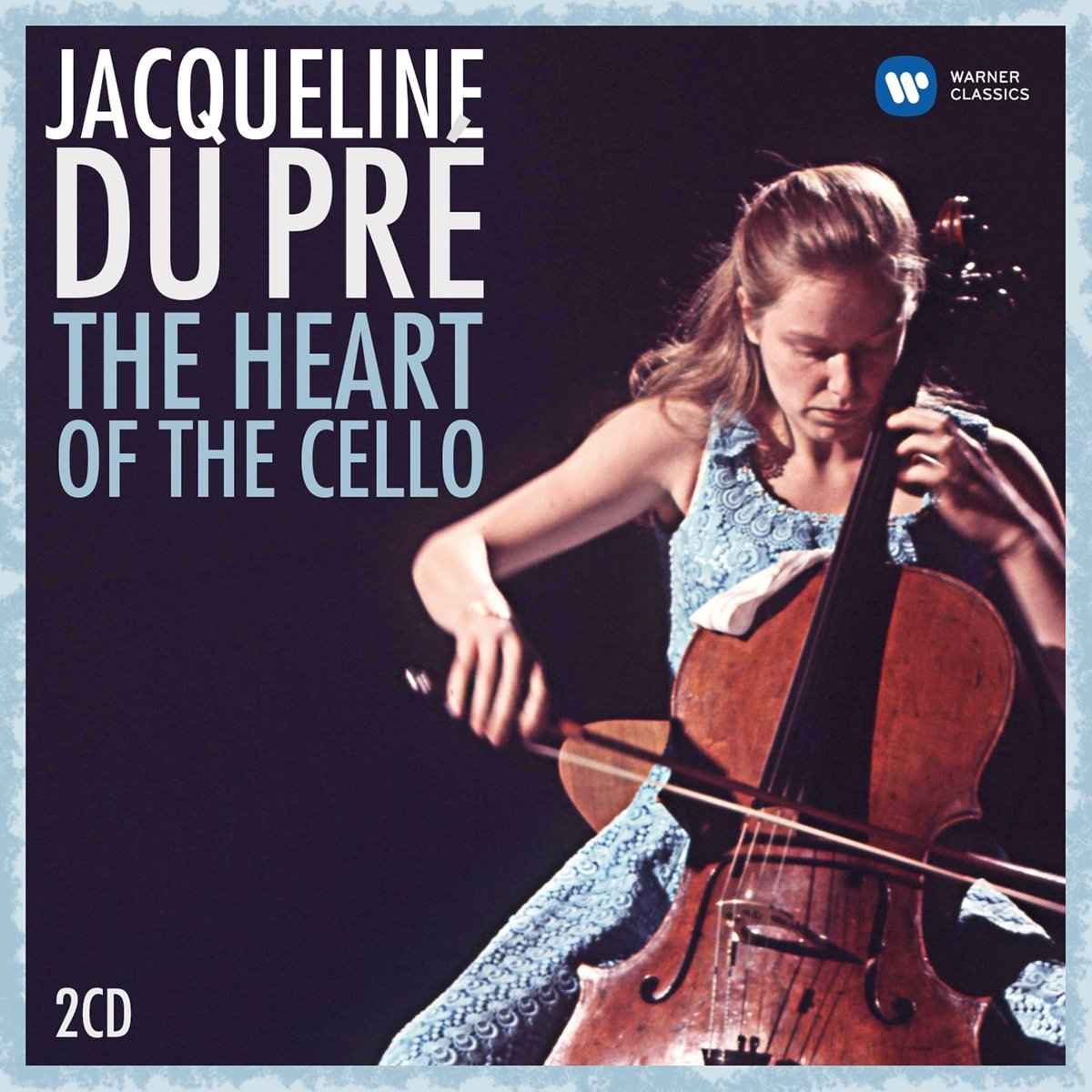

The double-CD Jacqueline du Pré: The Heart of the Cello (Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de) contains her famous 1965 recording of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85, recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra under the direction of John Barbirolli as well as her first ever recording, the Delius Cello Concerto, RT VII/7 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Malcolm Sargent. Dvorak, Saint-Saëns, Schumann, Haydn and Boccherini are the other composers recorded with symphony orchestras (CD1). The second CD contains chamber music of works by Bach, Brahms, Beethoven and others.

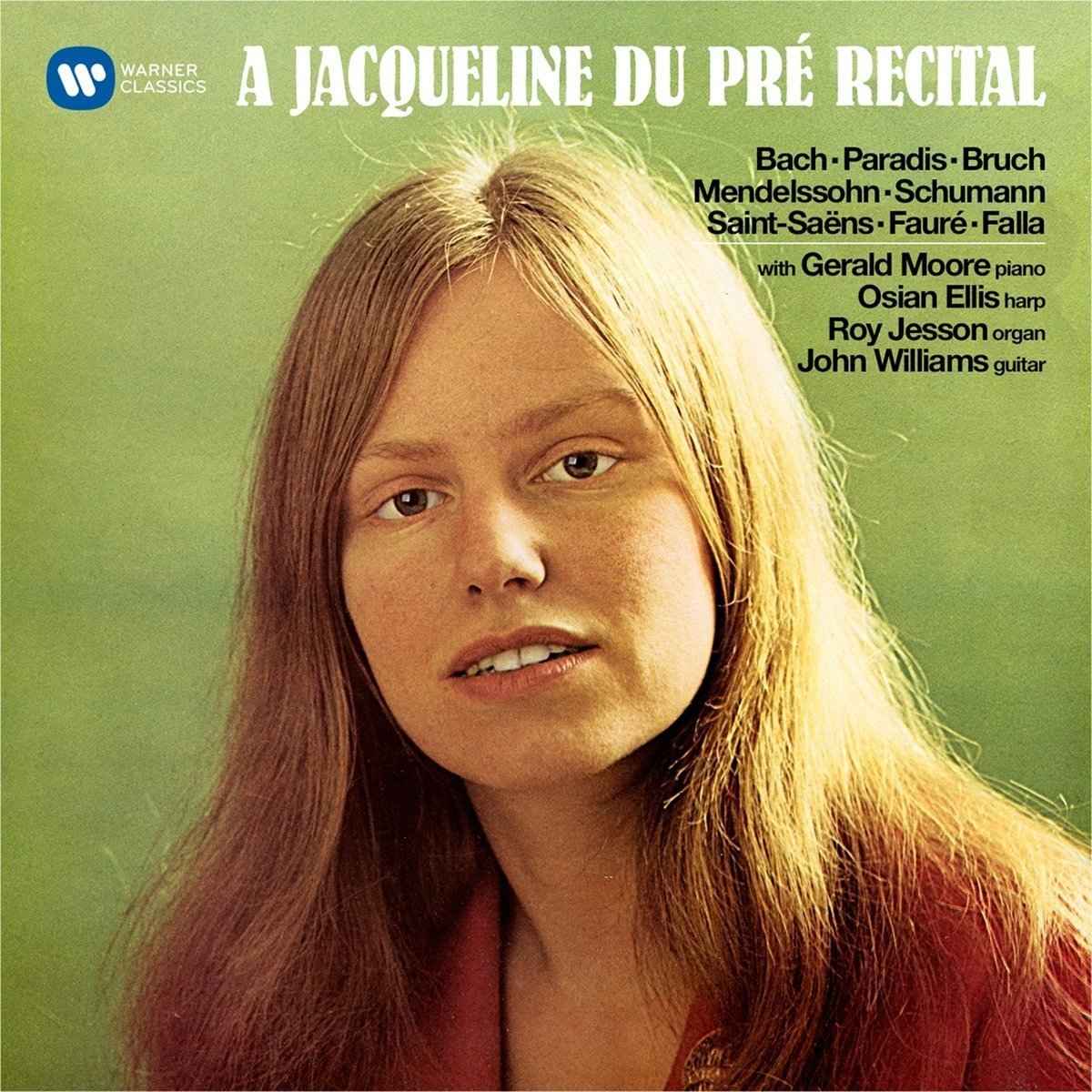

The CD A Jacqueline du Pré Recital (Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr) contains works by Bach, Bruch, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Falla as well as by the blind Austrian pianist-composer Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759-1824). The short pieces on this album as well as Bruch’s Kol nidrei (sheet music) were the first recordings Jacqueline du Pré made for EMI, although some of them were only issued twenty years later. In addition to Jackie on cello, we can hear Gerald Moore on piano, Roy Jesson on organ, John Williams on guitar and Osian Ellis playing the harp.

The booklets of the four CDs presented here were helpful in writing this article.

Article added on February 1, 2018 at 17:30 Berlin time. Last update on February 2, 2018 at 22:47. Detail added on February 9, 2019 at 12:05 Berlin time.