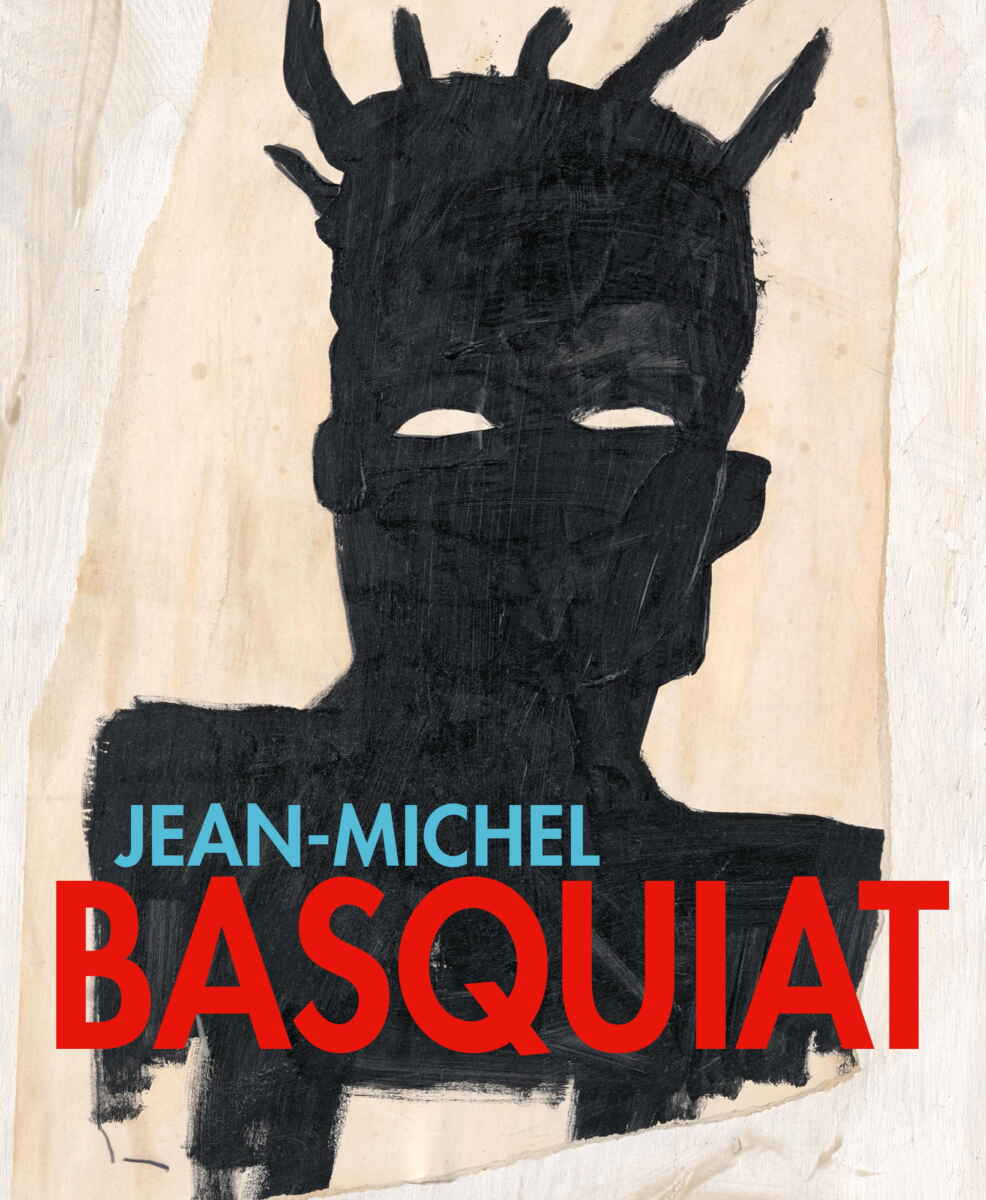

Curated by Dieter Buchhart and Antonia Hoerschelmann, the Basteihalle Albertina retrospective Jean-Michel Basquiat. Of Symbols and Signs presents in Vienna from September 9, 2022 until January 8, 2023 some 50 works by the great American artist who died too young (1960-1988).

The homonymous Prestel catalogue (English edition: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr; German edition: Amazon.de) offers on 216 pages an overview of the artist’s work as well as of the symbols and signs he used.

The Albertina Director Albrecht Schröder writes in the exhibition catalogue foreword that Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work combines various artistic genres and disciplines within his practice, which changed the 1980s art world. He put together elements of street art, comics, children’s drawings, advertising, his own Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage as well as African American, African, Aztec art and cultural histories, classical motifs, and mixed them up with contemporary heroes such as athletes and musicians. Therefore, Basquiat went far beyond pop art.

The use of linguistic signs and symbols is an integral part of Basquiat’s œuvre, hence the exhibition title. He used them in his very first drawings, in his poetic-conceptual graffitis, in his notebooks as well as in his later drawings and paintings.

Notably through signs and symbols, Jean-Michel Basquiat held up a mirror to society. He criticized colonialism, racism, violence against African-Americans, social discrimination and exploitation as well as the political system.

In his catalogue essay, the co-curator Dieter Buchhart examies Jean-Michel Basquiat’s polyvocal, symbolic language which was inspired by the cheap, poor, rund-down and dangerous New York City of the 1980s. Trains and walls were covered with graffiti and tags. Simple signs advertised services and sales. Traffic accidents, police violence, street musicians, newspaper and TV images influenced the young artist. To all of this he added the spiritualism of his Haitian heritage.

Dieter Buchhart explains that Jean-Michel Basquat was inspired by books about anatomy, geography, chemistry, alchemy, carograpyh, history, art history as well as the Bible, encyclopedias and dictionaires. They served as source material for his art-brut rhetoric of learned hip-hop.

According to Dieter Buchhart’s catalogue essay, in the spring of 1983, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s works achieved their highest complexity both in terms of visual motifs and their artistic energy. He resisted all canons of hierarchy and aesthetic value. His engagement with social and political issues reach a climax in these works.

According to the Vienna curator, Basquiat copied and transformed what was around him. He was inspired by William S. Burroughs’s cut-up technique, using cutting, ripping and pasting not just words. He used cut-and-paste or copy-and-paste sampling as is common in today’s internet age. The use of Xeroxes made it possible for Basquiat to reuse signs, motifs and fragments of drawings, or entire drawings. Basquiat both served and developed a cultural technique and aesthetic principle, a key cultural technique of modernity.

In 1984/85, the artist returned to the technique of the silkscreen, which he had already used in the work Tuexedo in 1983. Dieter Buchhart explains that, here (p. 147), the entirety of the central figure, which fills the canvas, was formed using 16 reproduced, densely inscribed and illustrated sheets in regular pattern—the human body is constructed of words, signs and symbols. Whereas in Untitled from 1983 (pp. 148/49), in contrast, Basquiat transferred a single large-format original of 28 collaged sheets of the same format (fig. 9) in the negative with white drawing and writing against a black background. He affixed the sheets to the canvas, lined up next to and on top of one another, but painter over the drawings with very few brushstrokes, both erasing them and bringing them together and, in doing so, emphasizing them.

In 1984/85, still according to Dieter Buchhart, Jean-Michel Basquiat eventually liberated himself from the rather orthogonal arrangement of the combined sheet and began to distribute them freely across the surface of the picture. In addition, he applied by way of silkscreen a whole range of individual motifs and drawings to the canvas, taking advantage of the full potential and possibility of this technique.

From this period also date over 150 works created in collaboration with Andy Warhol. Initated by the Swiss galerist Bruno Bischofberger, Basquiat’s friend Keith Haring described it as a kind of “physical conversation happening in paint instead of words”. Dieter Buchhart notes that Basquiat mostly accentuated and erased Warhol’s visual creations with his own visual elements. While Warhol, inspired by Basquiat, returned to his painterly beginnings of around 1960, Basquiat continued working on his drawings, collages, silkscreen paintings and assemblages. He later transferred the free play of visual motifs from his silkscreen paintings to his “allover collages.”

From 1986 to 1988, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art was clearly defined by an alternation between void space and fear of emptiness. He began working with a new kind of figural respesentation and, once again, expanded his repertoire of sources symbols and content, even if he maintained his primary techniques.

The curator stresses that Basquiat’s political messages were never intended to agitate nor as propaganda. But, in his work, he always took an uncompromising position. For Dieter Buchhart, the artist’s subjects have lost none of their urgency. He anticipated our copy-and-paste society, the madness of our brave new world of omnipresent suveillance and communication. His works are completely borne by the polyvocality of postmodernism. He fought indifference with words, word mutations and erasures. He fought against exploitation, consumerism, oppression, racism and police violence.

Jean-Michel Basquiat died on August 12, 1988 at his New York City loft at the young age of 27. The autopsy report from the office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Manhattan Mortuary, lists the cause of death as “acute mixed drug intoxication”.

This and much more, including an essay by Francesco Pellizzi entitled “Black and White All Over: Poetry and Desolation Painting”, can be found in the Albertina exhibition catalogue.

In short, by 1982, Jean-Michel Basquiat had become both the youngest-ever participant in documenta 7 and the first world-famous artist with Afro-American-Caribbean roots. He represents the art of the 1980s better than probably any other artist.

Catalogue: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Of Symbols and Signs. Hardcover, Prestel, September 2022, 216 pages. Order the English edition from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr; order the German edition from Amazon.de.

Exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat. Of Symbols and Signs: Basteihalle Albertina in Vienna from September 9, 2022 until January 8, 2023.

You can read more about Basquiat in the exhibition and catalogue review Basquiat by Himself. Check also my Art Basel 2019 article, where I spotted three great works by Basquiat at Van de Weghe Fine Art, including two works from 1983: the very yellow Onion Gun as well as the black and white Tuxedo, the latter is now part of the Nicola Erni Collection and is exhibited at the Albertina retrospective.

This article is based on the book Jean-Michel Basquiat. Of Symbols and Signs. For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this catalogue review are not put between quotation marks.

Exhibition and catalogue review added on September 24, 2022 at 19:39 Austrian time.