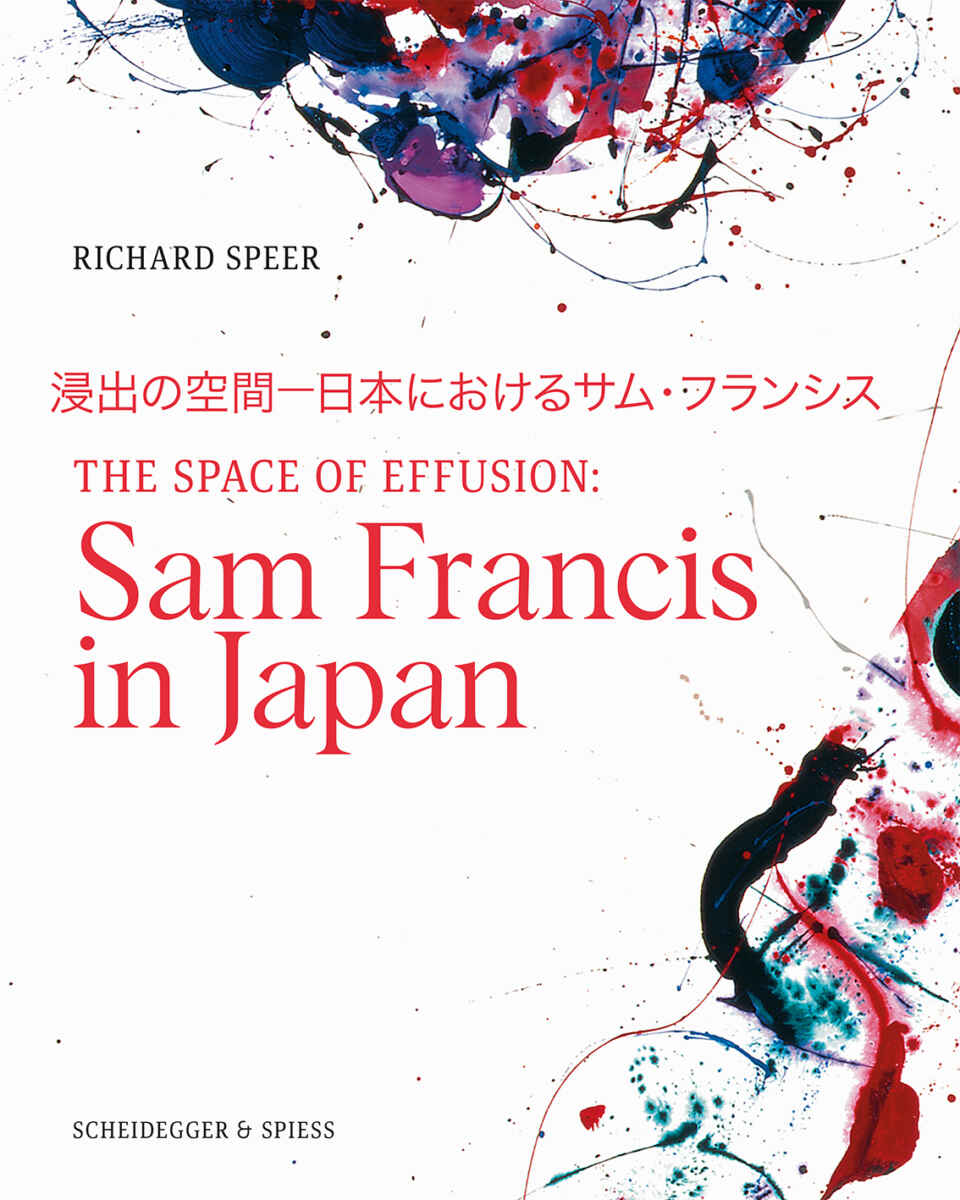

The American critic, curator and author Richard Speer has written a wonderful and enlightening book called The Space of Effusion: Sam Francis in Japan. It was published in connection with the Resnick Pavilion at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) exhibition “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing” scheduled for 2020-21, showing over 60 artworks. Because of the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic the show has been postponed. Check the museum’s website for details.

Richard Speer’s Sam Francis (1923-1994) monograph (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de) offers insights into the mutual influence between the American Abstract Expressionist and Japanese artists as well as East Asian aesthetics from the 1950s through the 1990s.

Sam Francis first traveled to Japan in 1957, a time when intercultural dialogue was still desperately needed between East and West in the post-World War II period. Incidentally, he was married five times and had four children. His third wife the Japanese painter Teruko Yokoi with whom he had a daughter, his fourth wife was the Japanese experimental video and film artist Mako Idemitsu with who he had two sons.

In the aftermath of the Treaty of San Francisco in 1951, Japan’s entry into the United Nations in 1956, and the period of reconstruction, development and growth that followed, the nation’s engagement with the West—which had commenced with the Meiji Restoration after 1868—increased exponentially.

The synergy between the Art Informel phenomen in Europe and the Gutai group in Japan had a seismic impact on the emergence of Japan as a player on the global cultural stage. Sam Francis was at ground zero at this singular moment. From his first Japan visit in 1957 until his death in 1994, he was part of this East-West cultural exchange. He was active in an avant-garde circle, including members of the nascent Gutai and Mono-ha movements.

The avant-garde circle included; architect and theorist Arata Isozaki; art critic Yoshiaki Tōno; poets Shūzō Takiguchi, Makoto Ōoka and Mamoru Yonekura; artist and ikebana flower master Sōfu Teshigahara; painters Toshimitsu Imai, Hisao Dōmoto, Hideo Kaido, Teruko Yokoi and Takako Idemitsu; Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi; ceramist Fujio Koyama; oil magnate and art collector Sazō Idemitsu; Gutai arists Jirō Yoshihara and Atsuko Tanaka; filmmakers Hiroshi Teshigahara and Mako Idemitsu; Korean-Japanese artist and Mono-ha theorist Lee Ufan; Mono-ha artist Kishio Suga; writer Taeko Tomioka; gallerist/impresario Kusuo Shimizu; composers Toshi Ichiyanagi, Tōru Takemitsu and Teizō Matsumura.

According to Richard Speer, in salons and izakayas, galleries, museums and universities, the ideological ferment among these creators in this time and place rivaled that of Paris in the 1920s, New York in the late 1940s and the East Village art scence of the 1980s.

Japanese art-lovers, collectors, poets, critics, artists, architects, filmmakers and composers looked at Sam Francis’s paintings—with their dynamic tensions between floating forms and evocative expanses of negative space—and saw with the Californian-born artist a familiar pictoral ethos, which seemed to harken to their own aesthetic heritage. In particular the white space in Sam Francis’s paintings, enveloping colorful gestures, pours and drips, struck Japanese viewers as a kinf of reimagining of their concept of ma, an energetically charged void or interval between objects.

Richard Speer mentions other well-known U.S. American artists such as Mark Tobey, Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, Franz Kline, David Smith, Morris Graves and Richard Serra, to name only a few, who were broadly influenced by East Asian aesthetics. However, the autor underlines, Sam Francis committed himself to Japan more comprehensively. He established art studios and built a home there, where he lived and worked for extended periods; collaborated extensively with Japanese artists, including his two Japanese wifes; integrated Japanese materials and techniques into his practice; studied and spoke Japanese, if haltingly; was instrumental in giving many of his Japanese colleagues their first exposure to the American and international art scenes. He did not just give “lip service” to East Asia—he walked the walk.

Overall, Sam Francis created some 1,152 unique works in Japan, a tally that is only second to his Southern California production among the seven major locales where he painted. Towards the end of the book, three pages (including photographs) are dedicated to two performances by Sam Francis: Sky Painting from 1966, a performance over Tokyo Bay with five helicopters, and Ski/Snow Painting from 1967, a performance at the Japanese winter ski resort in Naibara, involving skiers holding flares of different colors. According to the author, with these performances Sam Francis finally arrived at a place of comfort with the idea that his sensibility and the Japanese sensibility ahd come into sync.

In the first section of The Space of Effusion Sam Francis in Japan, Richard Speer dedicates chapters to the relationship and mutual influence between Sam Francis and the Japanese artists mentioned above. In the second section called “The Contested Void”, the author examines “The Emptiness That Is Not Empty”, “A Love Affair With Nothingness”, “Calligraphy, Chroma, and Decorativity”, “Assimilation or Appropriation?”, “Floating Worlds and Disapperance” and more.

Needless to say that this richly illustrated book is a must for all Sam Francis fans, not just in East and West.

Richard Speer: The Space of Effusion: Sam Francis in Japan. Hardcover, Scheidegger & Spiess, June 2020, 224 pages. Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

The front and the back cover of the book show details of Sam Francis’s work Untitled Four Panels from 1984 (acrylic on canvas, overall 427 x 685.5 cm).

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations from the monograph reviewed here are not put between quotation marks.

Book review added on July 12, 2020 at 13:56 German time. Title enlarged at 14:00.