The famous National Gallery in London opened in 1824 with the mission to bring art to the public. From the very beginning, the museum aimed to inspire artists and other visitors from all walks of life. Lucian Freud once said, ‘I go to the National Gallery rather like going to a doctor for help’.

The editors of The National Gallery. Paintings, People, Portraits book, Anh Nguyen and Rebecca Marks, stress that art is more than mere aesthetics – it is a repository of human experience, a mirror reflecting our hopes, struggles and desires. Over two centuries, the museum has welcomed over 300 million visitors. To mark this historic moment, this book presents over 200 paintings ranging from the 13th to the early 20th century, stories from a selection of people who love the National Gallery’s collection, and newly commissioned photographic portraits capturing the particular character of their subjects.

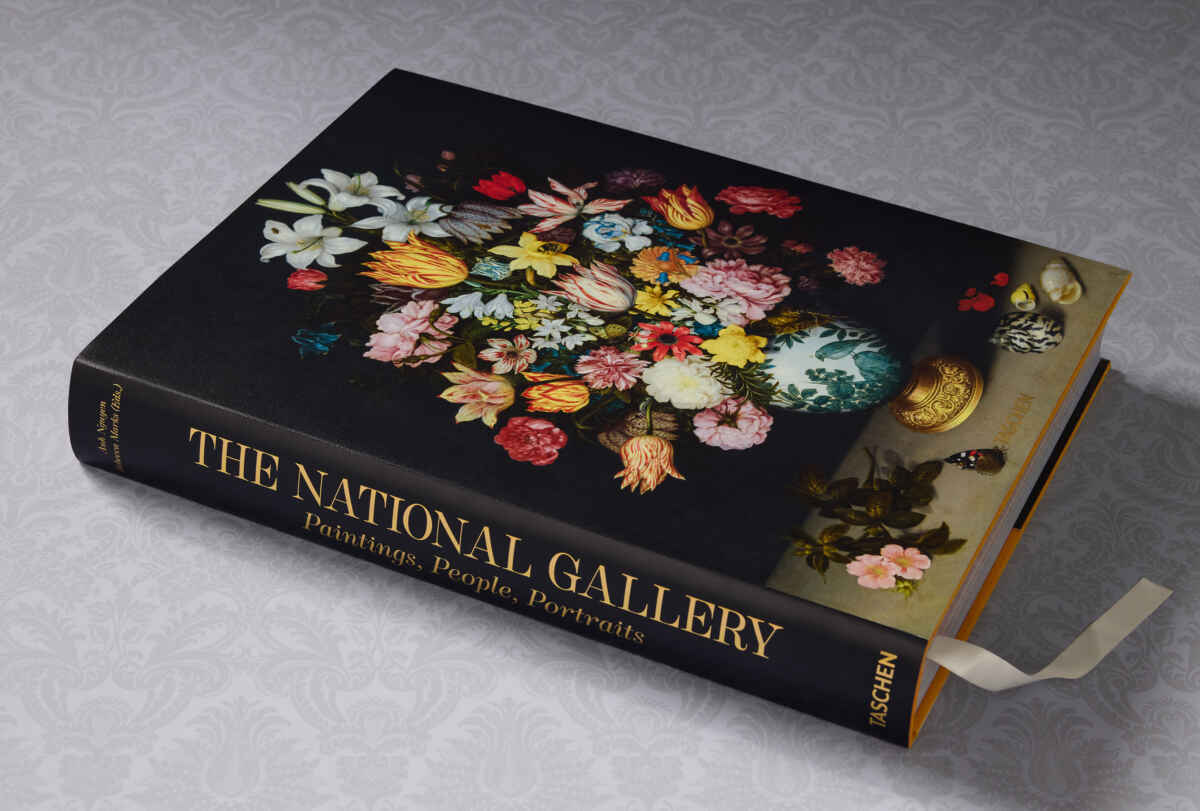

The National Gallery. Paintings, People, Portraits. Hardcover, Taschen Verlag, December 2024, 29 x 39.5 cm, 8.3 kg, 572 richly illustrated pages. With contribution by Annetta Berry, Christine Riding, Anh Nguyen, Rebecca Marks. Order the book from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

The museum’s Director of Collections and Research, Christine Riding, discusses the evolution of picture collecting in Britain, leading to the establishment of the National Gallery in 1824. She traces the gradual shift from private to public access to art, emphasising the role of collectors, connoisseurs and politicians in promoting art for its educational and social benefits.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890): Chair, 1888. Oil on canvas, 91.8 × 73 cm. Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890): Sunflowers, 1888. Oil on canvas, 92.1 × 73 cm. Photos copyright: The National Gallery, London. Photograph from the Taschen Verlag book.

The opening of the National Gallery, initially founded with works from private collections, marked a moment of transition towards a more accessible and national art culture. Before 1824, paintings were mostly hidden away in private collections inaccessible to all but a privileged few.

Christine Riding notes that the foundation of the National Gallery might be described as both the culmination and the greatest legacy of the Grand Tour. In addition, the Napoleonic Wars, that engulfed mainland Europe until 1815, restricted Continental travel, at the same time works of art from disbanded royal, aristocratic and ecclesiastical collections from France, Italy and beyond made their way across the Channel for sale. Therefore, London now rivalled Paris and Amsterdam as the centre of the old master market.

Christine Riding explains that the foundation of the Musée Français in 1793, from a former royal palace, the Louvre in Paris – with breathtaking displays of Greek and Roman antiquities through to contemporary Frenc hpainting – was admired by artists and wealthy tourists, which then encouraged the opening of British collections to visitors.

London town houses such as Grosvenor House and Apsley House offered more than a hint to the content and display of a future national collection. The drive to encourage access to historical art built on the foundations laid by the ground-breaking displays of British art at the Foundling Hospital (donated by William Hogarth and other artists from the 1740s) and other charitable institutions. Such initiatives culminated in the inauguration of public art exhibitions in London, again artist-led, particularly at the Society of Artists in 1761 and the Royal Academy of Arts in 1769.

Private collectors would lend their paintings to temporary exhibitions. According to Christine Riding, the first of these were organized by the British Institution (established in 1805), whose founding governors included collectors and patrons, John Julius Angerstein (1735–1823), a London-based financier, Sir George Beaumont (1753–1827) and the Reverend William Howell Carr (1758–1830) to name but three, who were to be critical to the formation of the National Gallery.

In 1815, the British Institution exhibited Continental art for the first time and managed to upset many British artists by tactlessly suggesting in the catalogue’s preface that they had much to learn from their seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish forebears. The focus now shifted to forming a national art collection that was accessible to everyone on a permanent basis.

Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702–1789): The Lavergne Family Breakfast, 1754. Pastel on paper mounted on canvas, 80 × 106 cm. Photo copyright: The National Gallery, London. Photograph from the Taschen Verlag book.

Some collectors and connoisseurs, like Sir George Beaumont, believed passionately that regular access to great art would improve contemporary painting, design and manufacturing, while politicians such as Robert Peel (1788–1850), who became a National Gallery Trustee in 1827, focused on art’s broader social impact through recreation and education. Comparable initiatives in Europe, including the Rijksmuseum, which was founded in The Hague in 1798, influenced the British.

Christine Riding writes about the strong feeling (embarrassment even) that the UK was lagging hopelessly behind its Continental neighbours and rivals, particularly France, was also a factor in the creation of the National Gallery.

The Viscount Fitzwilliam (1745–1816) bequeathed his collections in 1816 to Cambridge University, together with substantial funds for a new building. Francis Bourgeois (1753–1811) gave his collection to Dulwich College, south London; Dulwich Picture Gallery was the first purpose-built public gallery in Britain when it opened in 1817.

Christine Riding underlines that many of the most prestigious European public galleries had their origins in royal collections: the Museo del Prado in Madrid and the Musée du Louvre in Paris. However, in Britain, the royal collection had retained its original status, and its works of art were (as they are today) the property of the Crown.

Therefore, it was clear that a British national gallery would most likely spring from the acquisition of private collections. To that end, in 1823 both Beaumont and Holwell Carr offered to donate their collections of European paintings, on the condition that the UK government purchased works from the estate of Angerstein, who had died that year. Boosted by an unexpected financial windfall, Members of Parliament voted for some £60,000 to be allocated for ‘the purchase, preservation and exhibition of the Angerstein collection’ and the National Gallery – a modest group of 38 pictures of outstanding quality – opened to the public on 10 May 1824. This and much more can be found in Christine Riding’s contribution.

Annetta Berry’s essay offers a comprehensive and insightful survey of the National Gallery’s collection of Western art, starting with the devotional paintings of medieval Europe, and ending with the birth of modern painting.

Annetta Berry presents the historical context, revealing how changes in society, technology and ideology shaped artistic expression. She delves into the artists’ intentions, the influence of patrons and the broader cultural implications of the paintings.

In an attempt to capture the impact of the National Gallery on its visitors, the museum invited twenty-five ‘Ambassadors’ across different fields – from painters to students and actors to architects – to choose a favorite painting and to describe what it means to them. The feedback ranges from personal anecdotes to scholarly reflections.

Creativity is a dialogue – that crosses centuries and blurs the lines between creator and spectator. The texts by the ‘Ambassadors’ are accompanied and enhanced by the photographs of Mary McCartney and David Dawson, whose portraits try to encapsulate the essence of the twenty-five contributors, intertwining their personalities with the paintings that resonate most deeply with them.

According to Anh Nguyen and Rebecca Marks, it is the National Gallery’s ambition to become the world’s leading centre for research into historic paintings and to be a model of what a public research institution should be, sharing research with audiences in accessible and collaborative ways.

The National Gallery. Paintings, People, Portraits. Hardcover, Taschen Verlag, December 2024, 29 x 39.5 cm, 8.3 kg, 572 richly illustrated pages. With contribution by Annetta Berry, Christine Riding, Anh Nguyen, Rebecca Marks. Order the book from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

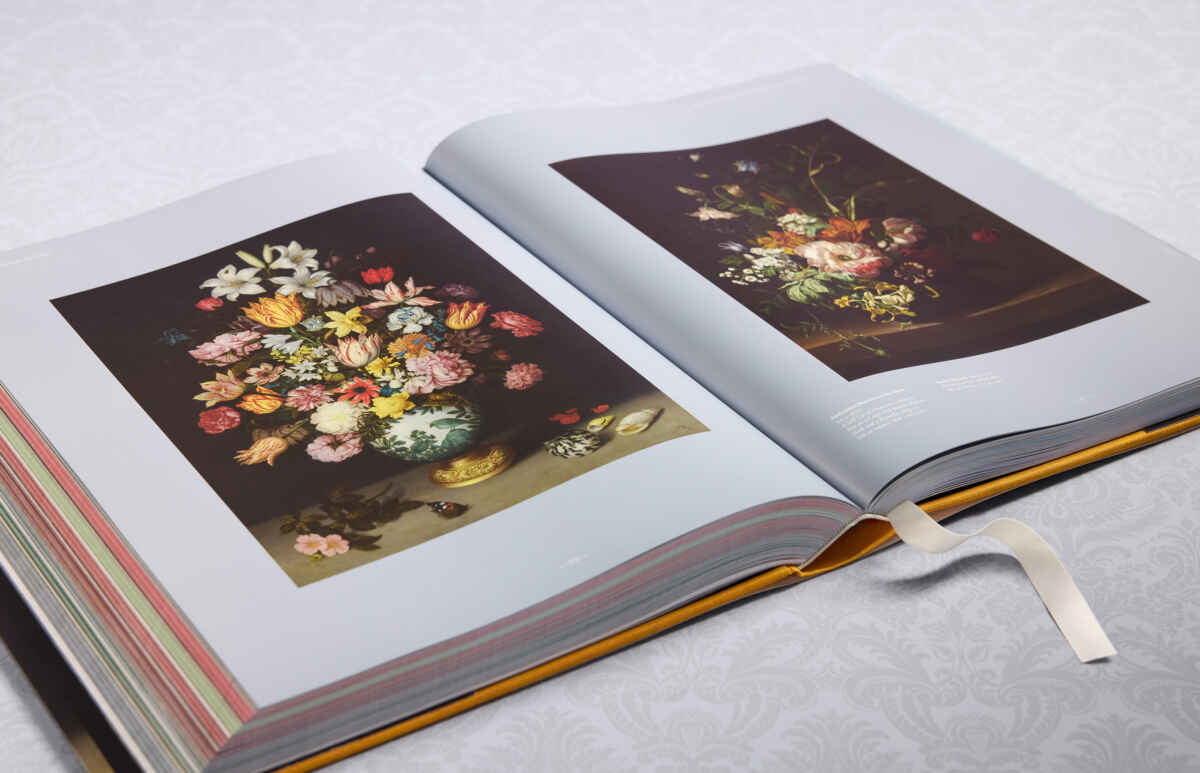

On the book cover (here on the left), you can find a work by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621): A Still Life of Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase on a Ledge with further Flowers, Shells and a Butterfly, 1609–10. Oil on copper, 68.6 × 50.7 cm. In the book, on the opposite side of the double page, you can find a work by Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750): Flowers in a Vase, about 1685. Oil on canvas, 57 × 43.5 cm. Among us, I would have put the Rachel Ruysch still life on the cover, because she is one of the greatest painters ever. Photos copyright: The National Gallery, London. Photograph from the Taschen Verlag book.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review have not been put between quotation marks.

Book review added on December 19, 2024 at 13:43 German time.