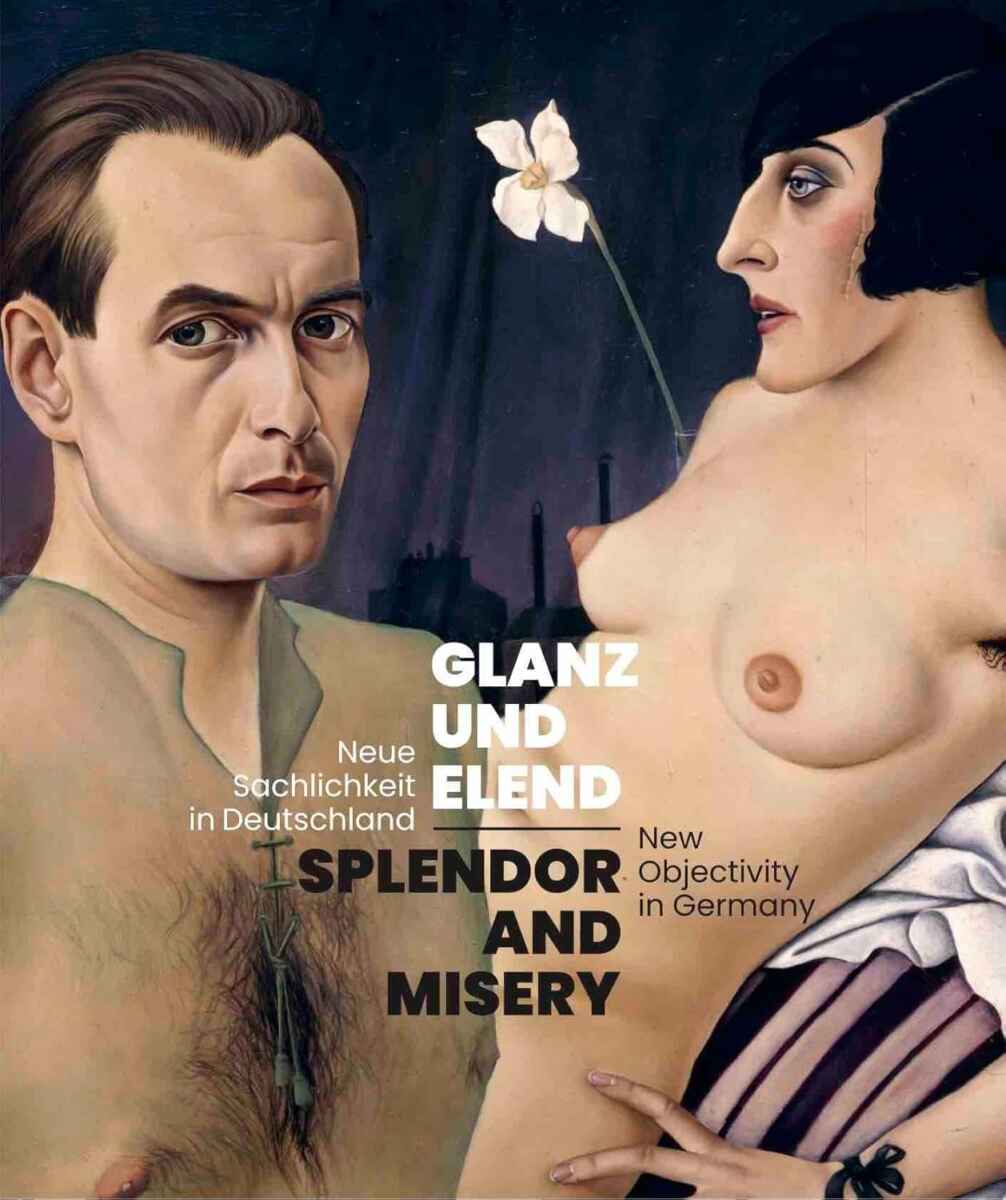

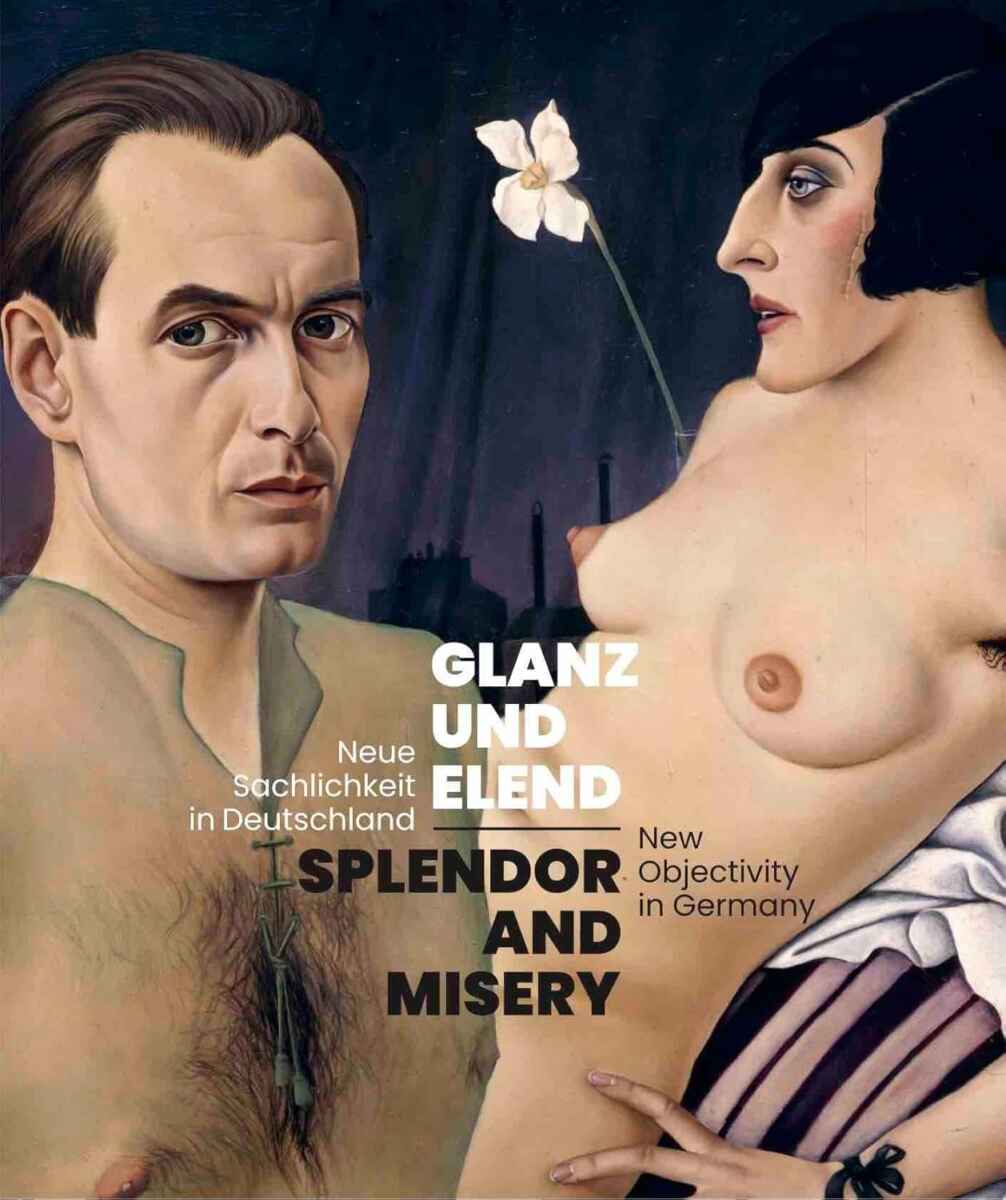

From May 24 until September 29, 2024 Vienna’s Leopold Museum presented the exhibition Splendor and Misery: New Objectivity in Germany. The show with some 150 exhibits from international museums and private collections, presented in twelve chapters, is already over. Luckily, the valuable catalogue remains available. Five specialists cover topics ranging from the rediscovery of reality between esthetics and ethics to literary observations on objectivity, the philosophy of new objectivity, the “new woman” on Germany’s streets and the new art scene, the portrait of new objectivity in Germany, culture politics and society of the Weimar Republic (1918-1933).

Hans-Peter Wipplinger, editor: Splendor and Misery: New Objectivity in Germany. Leopold Museum, Vienna, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2024, 336 pages with 275 illustrations (200 in color), 24 x 28.6 cm. With contributions by Daniela Gregori, Rainer Metzger, Aline Marion Steinwender, Hans-Peter Wipplinger, Thomas Zaunschirm. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the bilingual (English and German) catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Exhibition curator and catalogue editor Hans-Peter Wipplinger explains in the Prologue that the term New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub who, in 1925, organized the exhibition New Objectivity – German Painting since Expressionism (Neue Sachlichkeit – Deutsche Malerei seit dem Expressionismus) at the Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim.

Emil Orlik (1870–1932): Portrait of Nelly Neppach, 1925. Pencil, colored chalk, gouache on paper, 27.9 × 18.2 cm. Leopold Museum, Vienna. Photo copyright: Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger describes New Objectivity as a reaction, to the pathos-filled, illusionistic Expressionism, an individualist model, striving for inwardness and glorifying a Dionysian awareness of reality. According to the curator, Expressionism was no longer able to document the intellectual and political crisis situation and its reality in the Weimar Republic.

According to Friedrich Hartlaub’s 1925 definition, the two wings of New Objectivity were: the politically-oriented, socio-critical wing of the “Verists” on the left, which he called “the new naturalism”, and the Classicist and neo-romantic, traditional wing on the right, which he described as “the new Classicism”. The common ground of the two variants was a return to the ideals of a classical esthetics and a rejection of the color and form experiments of Expressionism, which were associated with the disaster of World War I and, therefore, with the failure of the Expressionist way of thinking.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger underlines that New Objectivity artists captured the zeitgeist. They derived the themes for their works not only from the aftershocks of World War I but also from the thriving Weimar Republic amusement industry, the new life plans pursued by independent and confident women, and from the encroachment of technological advancements upon nature and everyday life.

New Objectivity artists depicted people and things in a razor-sharp, sober and distanced manner. These new artistic approaches came to an abrupt end in 1933, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazis rose to power and enforced their art policy. Hans-Peter Wipplinger notes that, subsequently, politically suspect artists had to endure raids of their apartments and studios, were excluded from art institutions and associations, faced exhibition and employment bans. Some artists were murdered, some were forced into exile, many preferred inner emigration, while others chose to align themselves with the new regime’s art policy.

Exhibition view Splendor and Misery. New Objectivity in Germany. Photo copyright Leopold Museum, Vienna. Photograph: Lisa Rastl.

In his essay, “The Rediscovery of Reality between Esthetics and Ethics”, Hans-Peter Wipplinger writes that the young republic would last no more than 15 years, when civil war-like conflicts caused the democracy to fall apart. In 1933, the republic’s end was sealed by the seizure of power of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) under Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor.”

I would add that, indeed, it was a civil war-like situation with people killed on a weekly basis in conflicts between the left and right. Nevertheless, Adolf Hitler came to power democratically in free and more or less fair elections as part of a coalition government. But they quickly seized full power and moved on to a bloody dictatorship.

Back to the essay: After the defeat in the First World War, the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of the parliamentary Weimar Republic, the fresh art of New Objectivity was largely shaped by progressive artists on the political left who translated their pacifist ideas into art. In addition, Hans-Peter Wipplinger notes that the term New Objectivity emerged in Germany around 1922/23 as a reflection of the developments in politics and society. It was the central movement of the 1920s, which shaped this decade more than the Bauhaus and Constructivism.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger describes the artistic developments of Otto Dix and George Grosz, discusses terms such as Verism, neo-Classicism, Magical Realism, Golden Twenties, examines the examines the dark sides of the era such as hyperinflation, plummeting wages, supply shortfalls and high unemployment rates. The women’s departure into Modernism, emancipated women who carved out new opportunities and freedoms in the Weimar Republic, which gave them the right to vote in 1918. Some women were now wearing bob haircuts, short dresses, pantsuits and assumed androgynous or masculine attitudes. Magazines and feuilletons such as Die Dame or Elegante Welt accompanied the new trends. Vicki Baum and other writers had the protagonists of their novels and stories represent the zeitgeist.

Exhibition view Splendor and Misery. New Objectivity in Germany. Photo copyright Leopold Museum, Vienna. Photograph: Lisa Rastl.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger underlines that, in reality, full equality for women remained an illusion. The actual circle of “New Women” encompassed only a small, elitist group who were able to live up to the ideal thanks to their financial resources, while the newly formed, vast army of female laborers were merely seeking to escape into an illusion fueled by the media. Moreover, conservative forces intended to stop the spreading of this “dangerous, all too unfeminine” type of woman and to stabilize traditional gender boundaries. The relevant catalogue essay regarding the “New Woman”, “Your Body Is Yours’”, was written by Aline Marion Steinwender.

Women artists – including Lotte Laserstein, Kate Diehn-Bitt, Lea Grundig, Grethe Jürgens, Jeanne Mammen and Gerta Overbeck – used pictorial representations of the “New Woman” as a means to contribute to the construction of this type and to take possession of it, since they belonged to the protagonists of the phenomenon and hence themselves personified the pictorial content. Not mentioned in the catalogue, because she is not an artist of the New Objectivity movement: The often-portrayed artist Renée Sintenis was the typical “New Women”, portrayed in sculpture by the likes of Emil Rudolf Weiss and Georg Kolbe, photographed by Fritz Eschen, Frieda Riess and many others.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger underlines that, after the meteoric rise of the “New Woman”, the mirage disappeared almost as quickly. The 1929 crash and the following Depression and the rise of National Socialism, which called for women to return to conventional roles, erased the image of the independent and autonomous “New Woman” from everyday life and society’s collective memory.

In her catalogue essay, Daniela Gregori examines the New Objectivity portrait in Germany. She mentions Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub’s definition of Neue Sachlichkeit by defining everything it is not. His now famous letter written in May 1923 regarding a future exhibition expresses his interest in works by artists “who in the last ten years have been neither impressionistically relaxed nor expressionistically abstract, who have devoted themselves exclusively neither to external sense impressions, nor to pure inner construction”. Daniela Gregori underlines that the term he coined did not really take off until after Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub’s exhibition New Objectivity – German Painting since Expressionism (Neue Sachlichkeit – Deutsche Malerei seit dem Expressionismus) at the Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim finally opened in 1925 after some delay.

According to Daniela Gregori, Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub had in mind art which completely lacked pathos or illusion, an art of sober aloofness. She underlines that, owing to the sheer wealth of positions, however, there were also disparities, so that the style of New Objectivity had two distinct directions from the beginning. There was a right, conservative wing, characterized by a downright timeless Classicism, whose detachment invariably appeared dreamy or even slightly dreary. Georg Schrimpf, Alexander Kanoldt and Carlo Mense can be named as exponents of this variant. The other wing, which Hartlaub described as “garishly contemporary”, seeks “through a primitive obsession with observation, through a nervous obsession with self-exposure” to “un-cover the chaos, the true face of our time”.

Exhibition view Splendor and Misery. New Objectivity in Germany. Photo copyright Leopold Museum, Vienna. Photograph: Lisa Rastl.

Daniela Gregori notes that the various positions, united under the term Verism, addressed the social problems of the era in a critical and political manner, and thus illustrate – often in a style of painting reminiscent of the Old Masters – the entire misery of the not all that golden 1920s. The style of Magical Realism – a term coined in 1925 by the art historian Franz Roh – gradually evolved as a third movement within New Objectivity. From today’s perspective, however, such distinctions no longer appear particularly useful. Daniela Gregori mentions that Max Beckmann – an artist whose oeuvre is not commonly ascribed to New Objectivity – contemplated the direction his artistic journey was taking in a letter to Reinhard Piper in the last year of World War I: “My paintings and my graphic works are proof that you can be modern without producing Expressionism or Impressionism.”

Subsequently, Daniela Gregori’s essay explores significant aspects of portraits in the style of New Objectivity based on works featured in the Leopold Museum exhibition. This and much more you can discover in Hans-Peter Wipplinger, editor: Splendor and Misery: New Objectivity in Germany. Leopold Museum, Vienna, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2024, 336 pages with 275 illustrations (200 in color), 24 x 28.6 cm. With contributions by Daniela Gregori, Rainer Metzger, Aline Marion Steinwender, Hans-Peter Wipplinger, Thomas Zaunschirm. Accept cookies — we receive a commission; price unchanged — and order the bilingual (English and German) catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Among the artists covered in this catalogue are Max Beckmann, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Otto Dix, Dodo (Dörte Clara Wolff), George Grosz, Karl Hubbuch, Grethe Jürgens, Lotte Laserstein, Jeanne Mammen, Felix Nussbaum, Gerta Overbeck, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter and others.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this catalogue / book review of Splendor and Misery: New Objectivity in Germany have not been put between quotation marks.

Book / Catalogue review added on October 24, 2024 at 15:22 German time. Photographs added on October 25, 2024 at 11:24 German time; last detail added at 18:05.