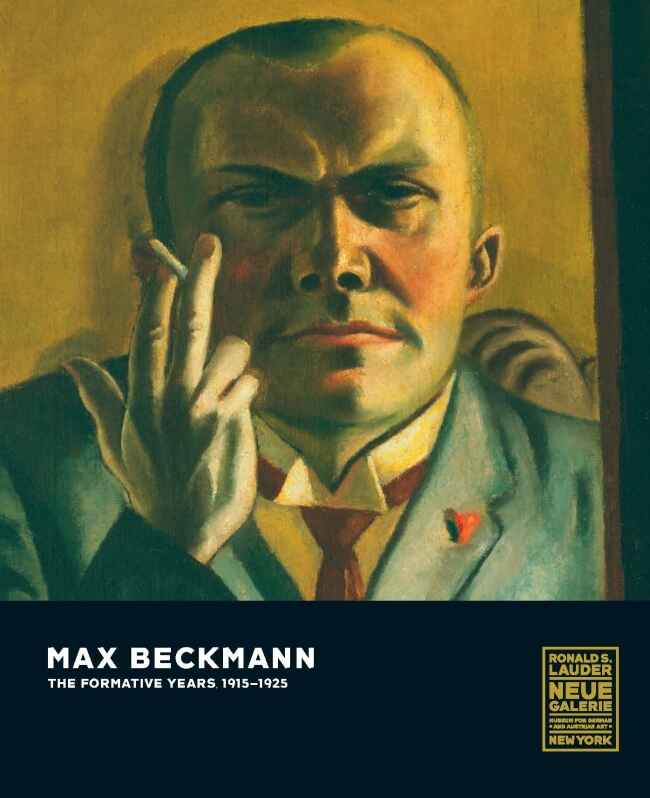

From October 5, 2023 until January 15, 2024 the exhibition and the epynomous catalogue Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925 at Ronald S. Lauder’s museum Neue Galerie in New York City feature approximately 100 paintings, drawings and print portfolios from museums and private collections in Europe and the United States. Accept all cookies to go directly to the catalogue’s Amazon page (we get a commission): Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925 offers an unprecedented focus on the decade in which Max Beckmann’s style moved away from his Impressionistic origins to the verist style of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) that defined his later work, although he later distanced himself from this term and favored “transcendent objectivity” instead.

Between 1917 and 1925, Max Beckmann became one of the most admired practitioners of representational painting. The Vienna-born Director of the Neue Galerie, Renée Price, writes in the catalogue “Foreword” that, in 1925, when he was 41 years old, Max Beckmann emerged as the crucial figure in the Mannheim exhibition New Objectivity: German Painting after Expressionism (Die Neue Sachlichkeit: Deutsche Malerie nach dem Expressionismus), even though he would later distance himself from that term. This turning point marks the endpoint of the Neue Galerie exhibition and explains its restriction to the years from 1915 to 1925.

Renée Price proudly stresses that the Neue Gallery managed to bring masterpieces to the New York show, including Fastnacht (Carnival, 1920) from the Tate in London, Der Traum (The Dream, 1921) from the Saint Louis Art Museum and Die Barke (The Bark, 1926) from a private collection.

The President of the Neue Galerie, Ronald S. Lauder, writes in the catalogue “Preface” that, as a teenager, he saw a triptych by Max Beckman in a NYC midtown gallery. He instantly saw the power and the strength of this extraordinary artist. He went right out and purchased every book he could find on Max Beckmann. Over the years, Ronald S. Lauder acquired a number of works by the artist.

The first extraordinary Max Beckmann painting to enter his collection was Galleria Umberto (1925; Mussolini had been in power for just three years, the artist was 41), which is prophetic in that it contains imagery of things to come: an Italian flag sinking into the water as if it is drowning; a dismembered figure, suggesting the torture during the Fascist era; a crystal ball offering a glimpse into the future and bugle sounding a warning.

Ronald S. Lauder underlines that for him, the highlight was the purchase, together with a fellow collector, of the Self-Portrait with Horn (1938), which Max Beckmann painted while he was living in exile in Amsterdam. The collector underlines that the artist left Germany in 1937 on the day after Hitler’s radio address on what he called degenerate art. This painting sums up the experience of refugees, torn from their homeland and forced to establish themselves in a new, unfamiliar environment. The horn announces a warning about the rise of Nazism and intolerance.

The monographic exhibition Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925 explores the early years of Beckmann’s career, from the time of his traumatic experiences during World War I through his success during the Weimar Republic, and finally to the period in which he was driven into exile.

The dramatic shift in Max Beckmann’s style and approach can be traced back to his involvement in World War I. With the outbreak of hostilities, the artist spent time in East Prussia as a volunteer nurse in 1914. He was profoundly affected by his experience in the combat, even though his involvement was short-lived.

In October 1914, in a letter to his wife Minna Beckmann-Tube, he wrote: “…my will to live is for the moment stronger than ever, even though I have already experienced dreadful things and died myself with them several times. Yet the more one dies, the more intensely one lives. I have been drawing, that protects one from death and danger.”

The following year, Max Beckmann served as a medical orderly in Belgium. In July 1915, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was discharged from service in 1917 and moved to Frankfurt to recover and his work changed as a result of the war.

The experience of World War I made the artist advance to a new pictorial conception. The painterly and romantic compositions of the pre-war years were replaced with more angular forms. His palette became darker and his use of paint more subdued. His subject matter evolved from history painting to embrace more contemporary subjects, sometimes viewed through a biblical lens.

René Price writes that a key step to Max Beckmann’s transformation was his focus on religious topics in paintings around 1917-18. Three key examples from major public collections are on display at the Neue Galerie. They reveal his stylistic development but also outline his horizon of interpretation as he sought to portray his own era using the pictorial formulas of the Passion of Christ and other biblical themes.

In September 1918, Max Beckmann wrote a short text entitled “Creative Credo”, where he defined his position in the current difficult times and indicated his intention to “be a part of all the misery that is coming.” In addition, he expressed a love for humanity, for “its meanness, its banality, its dullness, its cheap contentment, and its oh-so-very-rare heroism.”

Renée Price underlines that, around 1920, Max Beckmann was intensely preoccupied by the social and political fault lines of the era (I would add: of the Weimar Republic). That is why his work of this phase was considered verism and associated with the leftist wing of the Neue Sachlichkeit. The artist himself spoke of his art in terms of “transcendental objectivity”. Renée Price stresses that the subjects of these works prepare the ground, in terms of both form and content, for Max Beckmann’s later paintings.

Olaf Peters writes in his catalogue essay entitled “Transcendental Objectivity. Max Beckmann’s Modernity” that the artist adopted early on a position against the artistic avant-garde and did not shy away from public controversy when doing so. In 1912, Max Beckmann had a public dispute with Franz Marc of the expressionist artist circle The Blue Rider (Blauer Reiter).

In the context of the famous so-called “Bremen Art Dispute” of 1911 led by Carl Vinnen, Max Beckmann rashly dismissed Henri Matisse as one of the “untalented persons” and recommended instead 19th century painters such as Wilhelm Leibl, Max Liebermann and Adolf Menzel as “instructive artists”. Olaf Peters underlines that Max Beckmann did so, however, without siding with Carl Vinnen, who adopted a conservative, völkisch (racist-populist) position.

In the journal Pan in 1912, Max Beckmann argued for “Objectivity” (Sachlichkeit) and polemicized against Fauvism, Primitivism, and Expressionism. Above all, the artist took aim at the increasingly clear trend to abandon the representational image.

Olaf Peters underlines that Max Beckmann’s Impressionist painting style was ill-suited to mastering the large subjects such as crucifixion, shipwreck, earthquake, which he chose to represent. His dismissive reaction toward the contemporaneous trends of the avant-garde made it necessary for Max Beckmann to thoroughly rethink his own position because he had reached a dead-end. Influenced by Rembrandt van Rijn, Francisco Goya and the early Paul Cézanne, he emphasized spatial depth in his art. At the same time, Max Beckmann had no problem integrating the so-called decorative art he loathed into his visual cosmos, for example, by making use of the achievements of Cubism in pictorial autonomy.

World War led to an existential crisis but, at the same time, it prompted Max Beckmann to find a new form of objective perception and representation. It meant a break with his early painted work. He found a unique way of expression. Neverthess, he continued to see himself as sought to be objective and realistic together with a metaphysical claim to the interpretation of the world.

Olaf Peters writes that, around 1918–20, Max Beckmann tried to achieve that through an interpretive return to the national art tradition of early German and Netherlandish art, which Jürgen Müller addresses elsewhere in this catalogue. Beckmann experienced the crucial Northern influences that would be so important for his later reception and his understanding of himself as an artist in the nationalistically stoked climate of World War I.

By associating the medieval Gothic, which was considered authentically German, with Expressionism—which by then had acquired German connotations—and aiming this synthesis against the abstract, expressive tendencies of the avant-garde, Max Beckmann’s “transcendental objectivity” satisfied the concept of a “German art” that both artists and art critics demanded at the time, according to Olaf Peters.

The curator points out to the paradox that the artist rejected Expressionism and abstraction in equal measure while transcending them while moving toward the Neue Sachlichkeit.

Max Beckmann’s post-war subjects were often more violent as he confronted political intolerance and exposed poverty and social injustice. He developed a new approach to art, and one that helped him to process painful memories and that acknowledged recent artistic developments that he had previously criticized.

Olaf Peters remarks that Max Beckmann, unter attack from the National Socialists, asked his art dealer Günther Franke to emphasize that he was a truly German painter to protect him from future attacks. This turned out to be an illusion.

By appropriating and even mocking the tradition, Beckmann was emphatically culminating the turn away from the Christian religion and faith that he had described to his Munich publisher Reinhard Piper as early as in July 1919 in Frankfurt am Main:

“A new mystical feeling will form. Humility before God is over. My religion is arrogance before God, defiance of God. Defiance that he has created us so that we cannot love one another. In my paintings I accused God of everything he has done wrong.”

According to Olaf Peters, first, bitter mockery became Beckmann’s means for articulating his outrage. In the 1920s, the Heidelberg art historian Wilhelm Fraenger wrote that Max Beckmann’s work was marked by an irresolvable conflict between a constructive, objective will to order and a subjective will to express himself. The work produces an ambivalent sensation of order and compulsion, of norm and arbitrariness. In Wilhelm Fraenger’s view, the artist painted to combat solipsistic isolation and the individualistic-atomist structure of life today. He ordered, tamed, and disciplined the disorder of life. He was painting the world as it should be, even when it meant doing violence to it. Max Beckmann’s will to form, modeled on the early German masters, was to capture and order a senseless world and an almost unbearable randomness.

Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub used the term “Die Neue Sachlichkeit” as early as 1923. Two years later, he provided a survey of the artistic production of the past ten years, which he stressed had dedicated itself to a “positively tangible reality” and whose approach had been “neither Impressionistically dissolved nor Expressionistically abstract”.

Olaf Peters notes that Max Beckmann was represented with fourteen paintings at the 1925 Mannheim landmark exhibition Die Neue Sachlichkeit: Deutsche Malerei seit dem Expressionismus (The New Objectivity: German Painting since Expressionism), which was subsequently shown in several other German cities.

Olaf Peters stresses that, in the first half of the 1920s, Max Beckmann was one proponent of the Neue Sachlichkeit, perhaps even the main one. His work is associated with an emphatically representational painting that polemically distinguished itself from Expressionism and yet was still related to it.

The exhibition Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925 covers key topics: Portraiture and the Self-Portrait, Religious Paintings, Allegory, Still-Lifes, Landscapes, and Social Life in early Weimar Germany.

As always, these are just a few takeaways from an informative, richly illustrated catalogue with essays by six specialists.

Edited by Olaf Peters: Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925. With contributions by Anna Maria Heckmann, Jürgen Müller, Olaf Peters, Dietrich Schubert, Elisa Tamaschke and Christiane Zeiller. Prestel, hardcover, 2023, 256 pages, 9.25 x 2.05 x 11.22 inches, ISBN 9783791379944. Accept all cookies to go directly to the catalogue’s Amazon page (we get a commission): Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

This exhibition Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925 is curated by Olaf Peters, one of the world’s leading Beckmann experts, whose thesis at the University of Bonn was a broad monograph on Beckmann. Olaf Peters is a professor at Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. At the Neue Galerie in NYC, he has previously organized the exhibitions Otto Dix, Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937 (2014), Berlin Metropolis: 1918-1933 (2015-16) and Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of the 1930s (2018; order this 2018 catalogue from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de).

Max Beckmann in Frankfurt am Main exhibition review.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this exhibition and catalogue review of Max Beckmann: The Formative Years, 1915-1925 have not been put between quotation marks.

Book and exhibition review added on January 8, 2024 at 14:19 German time.