Added on November 1, 2011: Beijing’s tax authorities have ordered Ai Weiwei to pay 15 million Yuan (€1.8 million) for “tax evasion”.

Added on June 22. 2011: According to the Chinese news agency Xinhua, Ai Weiwei was released on bail on June 22, 2011 “because of his good attitude in confessing his crimes as well as because of a chronic disease he suffers from.” The artist was accused of tax evasion and destruction of accounting documents. He is reportedly willing to pay the outstanding taxes. His sister, Gao Ge, said that Ai Weiwei has returned to his home.

Ai Weiwei: Interlacing. Photos and videos by the imprisoned Chinese artist

Article added on June 1, 2011: The imprisoned Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has a close relation with Switzerland. The Lucerne gallery owner Urs Meile is representing him since 1997. The former Swiss ambassador in China and the world’s leading contemporary Chinese art collector, Ueli Sigg, has helped the artist emerge on the art scene. Ai Weiwei’s first solo museum exhibition took place at Kunsthalle Bern in 2004. Currently, the first major exhibition of photos and videos by the Chinese artist is on view at Fotomuseum Winterthur (until August 21, 2011; from February 21 to April 29, 2012 at Jeu de Paume, Paris): Ai Weiwei: Interlacing (catalogue: Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr)

Ai Weiwei (*1957) is a conceptual artist, sculptor, photographer, architect, blogger, twitterer, cultural critic, interview artist, dissident and political activist. The Fotomuseum Winterthur exhibition title “Interlacing” refers to Ai Weiwei’s networking and communicating skills. He brings life into art and art into life. He does not separate art from life, a bit like Joseph Beuys with his concept of the artist as a “social sculpture”, although Ai Weiwei rejects the association with Beuys. The Chinese artist rather emphasizes the importance of Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol for his work. From those artists, Ai Weiwei developed his self-consciousness as a conceptual artist, which is in contrast to the Chinese tradition where the perfect brush stroke is important. Ai Weiwei’s credo as an artist is rather: “We have to set up a structure”, in the way Andy Warhol put up his “Factory”.

In this context, Urs Stahel pointed out to the architect Ai Weiwei who, incidentally, had never had any training as an architect: he would tell his collaborators to build a wall with only two-thirds of the bricks they would normally use; it was up to his collaborators to come up with a way to do it.

Ai Weiwei’s life became a work of performance art, followed in total by 17 million people all over China from 2005 to 2009. His blog was filled with some 200,000 thousand cell phone photographs; after his blog was shut down by the authorities in 2009, Ai Weiwei continued communicating with his followers through twitter messages.

In an exclusive interview with the director of Fotomuseum Winterthur, Urs Stahel told me that the initial idea about a photo exhibition came from a 2009-talk with Urs Meile, the gallery owner representing Ai Weiwei. Meile told Stahel about the thousands of 1983-1993 New York photographs by Ai Weiwei, which the artist only developed after his return to China. In May 2009 and in May 2010, Urs Stahel met Ai Weiwei in Beijing. They took the decision to organize a photo and video exhibition. Since July 2010, one of Ai Weiwei’s assistants was charged with the project. The assistant selected some 30,000 out of 200,000 blog photos by Ai Weiwei. On twelve monitors, 2000 photos per monitor are shown in slide shows in Winterthur. On two additional monitors, an important selection of Ai Weiwei’s blog texts are shown (in an English and a German translation; the original blog was in Chinese, using also pictograms for “subversive” messages). The assistant also chose some 17 hours of video footage to be shown in the exhibition, always in connection with Ai Weiwei himself.

The Fotomuseum Winterthur exhibition was set up under the supervision of Ai Weiwei, who was only unable not approve the final images selected for the accompanying catalogue because he ended up in prison in an unknown location on April 3, 2011; incidentally, only as late as on May 20, 2011 Ai Weiwei was accused of tax evasion and of destroying accounting documents, according to the state-run Xinhua news agency.

During my interview, Urs Stahel emphasized the importance of Ai Weiwei spending his youth with his father, the once respected poet Ai Qing, who had been banned from writing for twenty years. Mao had banished the poet for his “revisionist thoughts”. As a consequence, the father spent thirteen years cleaning toilets, accompanied by his son.

The irony is that, in 1981, Ai Weiwei had left China for the USA because he considered his mother country too politicized. After his return to China in 1993, he became the quintessential political artist.

In the “Interlacing” catalogue, Urs Stahel is quoting a 2009 interview Ai Weiwei gave to the International Herald Tribune (IHT): “I came to art because I wanted to escape the other regulations of society. The whole society is so political.”

Both in my interview as well as in the catalogue, Urs Stahel points out to the fact that Ai Weiwei sees his role as “an active part of the enlightening, clarifying elements in the world”, especially in a totalitarian society such as China.

His self-questioning in his visual diary about himself and the world found an important echo in the Chinese online community. Therefore, Ai Weiwei was and is a thorn in the regime’s side.

One of the artist’s assistants told me that Ai Weiwei’s Fake Design office in Beijing is under close supervision by the regime, which installed a surveillance camera at the entrance to monitor all visitors. During the height of the “Jasmine revolution” in Egypt and Tunisia, the regime had a van parked outside the office 24-hours.

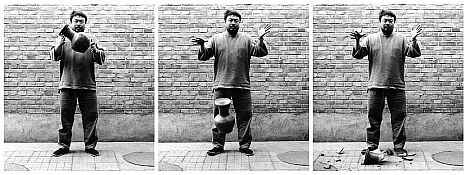

Ai Weiwei: Dropping a Han-Dynasty Urn, 1995 Triptych, C-prints, each 150 x 166 cm. Photos copyright © Ai Weiwei.

The famous 1995-triptych Dropping a Han-Dynasty Urn, which is part of the exhibition, is a sign of protest by Ai Weiwei against the regime’s destruction of the Chinese cultural heritage. Not only artefacts are lost, entire city districts are destroyed and completely rebuilt. Ai Weiwei opposes the tabula rasa policy explicitly in the 2002-2008 Provisional Landscapes series, of which 75 inkjet-prints are part of the Fotomuseum Winterthur exhibition.

The Chinese regime seems to be fragile. It reacted harshly to prevent any spreading of the “Jasmine revolution” from the Arab world to China. At the same time, the left hand of the regime does not know what the right hand is doing. The regime is incompetent and corrupt. Part of the explanation – and the only hope – is that the Communist Party may not be as monolithic as it may look.

To imprison Ai Weiwei is a sign of incompetence of the Chinese regime. It was the best way to make the artist even more famous both in China and around the globe. The same had happened in 2010 with the crackdown on the Peace Nobel Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. Both of them have become household names around the globe.

Ai Weiwei considers himself a connecter, rebel, communicator and enabler. His way of interlacing was what frightened the hardliners of the Chinese Communist Party.

In “Communist” China, the top one-percent of society owns sixty percent of the country’s wealth. The emperor is naked and knows it. Anyone pointing out to such “weaknesses” becomes an enemy of the state. The regime needs reform, the faster the better.

Ai Weiwei “believes that China has yet to experience a large-scale modernist movement, whose basis is the liberation of human nature and the spread of humanity. Democratic politics, material wealth and the education of all citizens in the society are the soil for modernism, yet all of these are only idealized pursuits for a developing country like China. Modernism is the questioning of traditional humanist values and critical thinking of living conditions, and is so far missing in Chinese society, where individual and intellectual value is largely dismissed. Ai’s photographs and act of photographing hold up a mirror to this void, and show how he strives to fill it” (Carol Yinghua Lu in the Winterthur catalogue).

Catalogue and exhibition Ai Weiwei: Interlacing, available in English, French and German, organized by Urs Stahel, Fotomuseum Winterthur (Switzerland) and Jeu de Paume (Paris, France), published by Steidl Verlag Göttingen (Germany), 495 pages. Order it from Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr.

Photograph of the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. Photo copyright: Ai Weiwei.

Article about Ai Weiwei: Interlacing originally added on June 1, 2011. Uploaded to our newly designed pages on October 19, 2020.