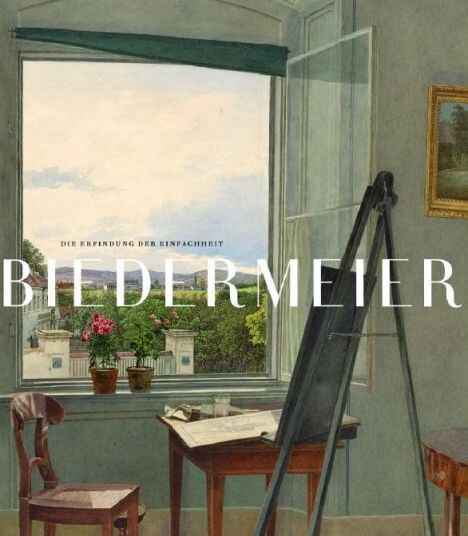

The exhibition Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity was originally conceived at the Milwaukee Art Museum and then enthusiastically embraced by the directors of the Albertina and the Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin, who have published widely on Biedermeier topics. Hans Ottomeyer has already published the two main theses of the exhibition in his 1980s-book Biedermeiers Glück und Ende … die gestörte Idylle 1815-1848.

The Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity catalogue (Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.co.uk; German edition/Deutsche Ausgabe: Amazon.de) and exhibition present some 400 art works, ranging from paintings, drawings, furniture and decorative objects to clothing. The works of art were made in Germany, Austria, Bohemia and Denmark.

The basic characteristics of Biedermeier became apparent even before 1800, and up until around 1830 it continued to develop through simplification, the natural beauty of materials and the clarity of form. Examples of Biedermeier can be found as late as the 1860s.

In the catalogue Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity, Laurie Winters explains that in the 20th century, with two notable exceptions, Biedermeier has largely been associated with the period of the “restoration” following the Napoleonic Wars starting in 1815 and ending with the death of the Austrian Emperor Franz I in 1835 or with the outbreak of revolution in 1848.

Biedermeier has also largely been interpreted as a middle-class art made quickly and cheaply with middle-class interests in mind. Biedermeier was considered the art and period of the emerging bourgeoisie, a reflection of bourgeois modesty in taste after the Napoleonic Wars in the exhausted postwar economies.

According to Laurie Winters, the catalogue and exhibition Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity take the unconventional perspective of the aesthetics to explain Biedermeier, which is “identified as a term for an artistic era characterized by an emphasis on functionality and natural beauty… In its pure form, Biedermeier is characterized by an overall abstraction and geometry, brilliant color, and a lack of superficial ornamentation.”

The exhibition and catalogue exclude exclude the many revivalist and historical forms of design and style that developed parallel to Biedermeier, as well formal, backward-looking forms such as the ornamental antique, the Empire style, a literature-based Romanticism, neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance and neo-Baroque styles.

The first of the two major theses of the exhibition and catalogue is to demonstrate the startling affinities of Biedermeier with designs of the 20th century, but without discussing its anticipation of modernity in detail. Some exhibits foreshadow not only works by the Wiener Werkstätte, but even by the Bauhaus. The second major thesis is that Biedermeier was not a bourgeois invention, but an achievement of the nobility and the courts, especially the Imperial court in Vienna.

The book and exhibition further illustrate the interconnections among the major cities of Central and Northern Europe following the Congress of Vienna, emphasizing the participation of these cities in a common culture. Laurie Winters explains that artistic training at public drawing schools and the extensive travels of many artists contributed to an international style and culture.

With the restoration of traditional hegemonies after 1815, Emperor Franz I of Austria resumed the leadership of the Germanic states, ranging from the powerful kingdom of Prussia to city-states such as Frankfurt am Main, Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck.

The ruling federal body or diet met in Frankfurt am Main and functioned as a sort of permanent congress of ambassadors. England, Holland and Denmark were represented because they controlled Hanover, Luxemburg and Holstein respectively.

From as early as the late 1790s, a lively cultural exchange took place between artists located on the north and south shores of the western end of the Baltic Sea. The existing links between Denmark and the German states were strengthened.

A cultural exchange took place between Vienna, Berlin and Copenhagen. The first art academy in Northern Europe was established in Copenhagen in 1738, offering free classes to students from Dresden and Berlin too. German artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and Georg Friedrich Kersting were attracted. Around 1830, German was spoken as much as Danish in the academy in Copenhagen. The exchange was mutual, and Danish artists studied and worked in Berlin, Dresden and Munich.

Berlin and Vienna were important artistic centers. Berlin was the capital of Prussia and, behind Vienna, the second largest city in the German Confederation. The Berlin University, founded in 1810, attracted some of continental Europe’s most brilliant minds.

Vienna, the capital of the Austrian Empire, was the most important city of the German-speaking world. It was the artistic center of the Habsburg Empire, hosting its vast and rich collections. Its fine arts academies attracted students from all over Europe. Many artists traveled through Vienna to Rome where they convened with the Nazarenes, Joseph Anton Koch and the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen.

The term “Biedermeier” was coined much later, around 1855-57 and is both nostalgic and critical in nature. The physician Adolf Kussmaul and the lawyer Ludwig Eichrodt created the fictional character Weiland Gottlieb Biedermeier, a recently deceased schoolteacher from Swabia, a common man with an uneventful life, as a parody for the bourgeois readers of the Munich satirical weekly Fliegende Blätter (Flying Papers). Only from the 1890s onwards, the term Biedermeier was used to describe the artistic and cultural period preceding the revolution of 1848 in a naive and nostalgic way, biased by the echo of the Fliegende Blätter.

A new thinking on the role of the bourgeoisie in the Biedermeier period came as late as 1987 by Christian Witt-Dörring in his essay on furniture. It was followed by the 1987 landmark exhibition Biedermeiers Glück und Ende … Die gestörte Idylle 1815-1848 by Hans Ottomeyer at the Münchner Stadtmuseum, devoted entirely to the decorative arts (book in German). Laurie Winters describes it as a “seminal exhibition”, a term by many reviewers also used for the 2007 exhibition at the Albertina in Vienna. Winters asserts that “Ottomeyer, like Witt-Dörring, defined an entirely new way of thinking about the Biedermeier period.”

“Witt-Dörring and Ottomeyer, working independently of each other in Vienna and Munich, both refuted the well-entrenched notion that Biedermeier art was made cheaply and quickly for the middle classes.” On the contrary, their research proved that the best and simplest examples of Biedermeier furniture were commissioned for the courts and the aristocracy.

In their 1993 exhibition Wiener Biedermeier: Malerei zwischen Wiener Kongress und Revolution, Albrecht Schröder and Gerbert Frodl removed the pejorative taint associated with Biedermeier paintings. Painters such as Erasmus von Engert and Franz Ebyl were given new prominence among the leading artists of the early 19th century.

According to Laurie Winters, the publication The World of Biedermeier by Karl Kemp, Linda Chase and Lois Lammerhuber (2001 book at Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk) is the most important recent contribution to the study of Biedermeier furniture and decorative arts, encouraging “fresh perspectives and connection with the art of the early twentieth century.”

The exhibition and catalogue Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity take the research of Hans Ottomeyer and Christian Witt-Dörring as the starting point. The aesthetics are used to reassess the Biedermeier period and its arts (history, art, furniture). Biedermeier is interpreted as “a highly cultivated and refined quest for simplicity and purity of form that has its roots in the late eighteenth century.”

The exhibition catalogue: Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity. Editors Hans Ottomeyer, Klaus Ablrecht Schröder, Laurie Winters. Texts by Hans Ottomeyer, Laurie Winters, Laurie A. Stein, Christian Witt-Dörring, Sabine Thümmler, Jutta Annette Page, Paul Asenbaum, Cornelia Reiter, Gisela Maul and Albrecht Pyritz. Hatje Cantz, September 2006, 400 p. Order the English edition from Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.co.uk; German edition/Deutsche Ausgabe Die Erfindung der Einfachheit bestellen bei Amazon.de.

The Albertina is an excellent choice of location for the exhibition since the Viennese furniture makers Danhauser decorated the Albertina in the then new Biedermeier style in 1822.

The exhibition schedule:

– Milwaukee Art Museum: September 16, 2006 – January 1, 2007

– Albertina, Vienna: February 2, 2007 – February 13, 2007

– Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin: June 8, 2007 – September 2, 2007

– Louvre, Paris: October 15, 2007 – January 15, 2008

Related book in German: Biedermeiers Glück und Ende … die gestörte Idylle 1815-1848. Hans Ottomeyer, Hrsg. Hugendubel, TB, 2. Auflage 1987, 768 S. Buch bestellen bei Amazon.de.

Book review added on March 5, 2007. On July 18, 2020 review moved from the old cosmopolis.ch Microsoft Frontpage website to the new WordPress website.