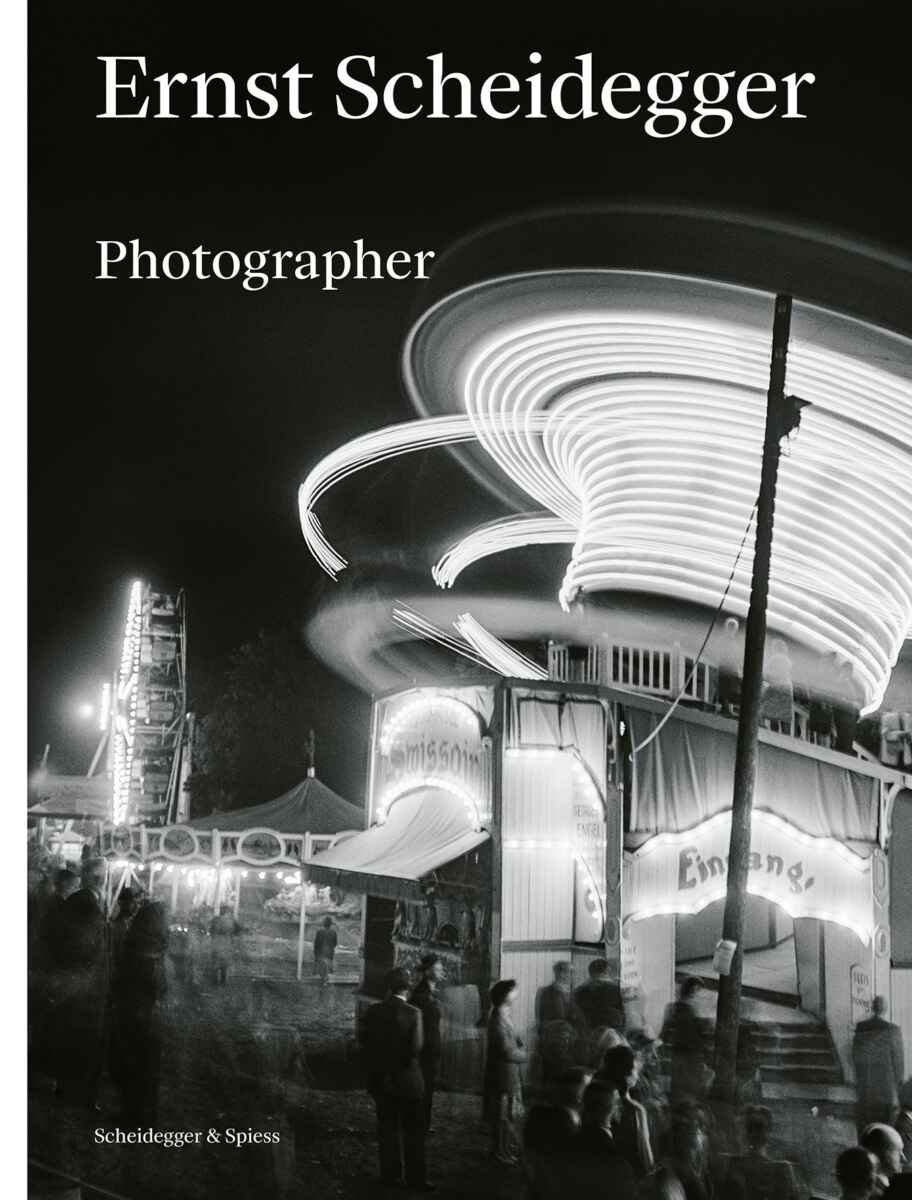

From October 27, 2023 until January 21, 2024 Kunsthaus Zurich is presenting the exhibition Ernst Scheidegger: Photographer (English catalogue — we earn a commission: Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr, Amazon.co.uk; German edition: Amazon.de).

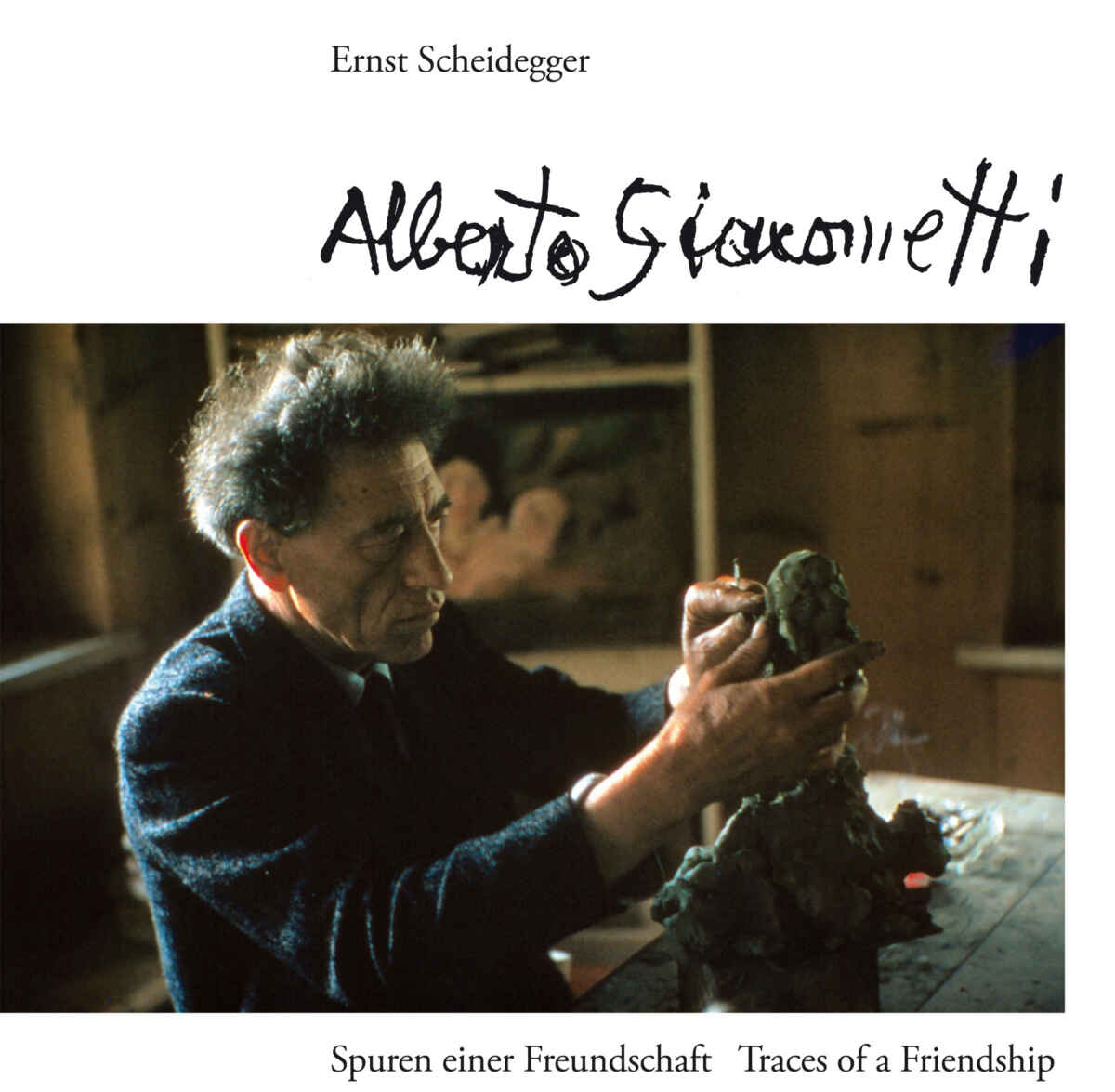

Ernst Scheidegger (1923-2016) was one of Switzerland’s most important photographers, famous for his photographs showing Alberto Giacometti, his atelier, his sculptures, paintings and other works. There’s even a book about their friendship. Ernst Scheidegger was an artist, book publisher and gallery owner.

Curated by Philippe Büttner, the Kunsthaus Zürich exhibition is marking the 100th anniversary of Ernst Scheidegger’s birth and focusing mostly on black and white photographs he shot between the 1940s and the mid-1980s.

In the catalogue, the MASI Lugano — where an Ernst Scheidegger exhibition will follow in 2024 — Director Tobia Bezzola reminds readers that, originally, the photographer had embarked on a career as a Magnum photojournalist and reporter, which ended abruptly in the spring of 1954. On May 16, his friend and mentor, the fellow Swiss photographer Werner Bischof died in a car crash in the Peruvian Andes and, just nine days later, his friend Robert Capa, the world’s most famous war photographer, was killed when he stepped on a land mine near Thái Bình in Vietnam.

The photo agency and cooperative Magnum had originally selected Ernst Scheidegger for the Indochina assignment and had accredited him accordingly. But the Swiss was the only one able to obtain a visa in time to cover a state visit in Egypt, Robert Capa agreed to take his place flying to Vietnam, despite having previously sworn that he was finished with war.

These two tragic deaths devasted Ernst Scheidegger to the point that he could barely talk about them and abandoned his career as photojournalist for Magnum. Instead, he took up a position as a lecturer at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. Therefore, his early work as a photographer ended in 1956.

The catalogue features some 66 early works made between 1945 and 1955. Most of them have never been shown to the public before. In addition, you can find 91 artist portraits and photographs of ateliers and artworks. Add to this 12 photos of Alberto Giacometti, his atelier and artworks, as well as 11 Chandigarh color photographs of the 1950s. At the very end, there is a photo by Leonardo Bezzola showing Ernst Scheidegger in Heimiswil (Switzerland) in 2003, holding up a frozen marten.

Tobia Bezzola stresses that Ernst Scheidegger would remain true to photography his whole life but, henceforth, he would be dedicated to a very different kind of photography, which changed his visual language and style.

Tobia Bezzola writes that, recalling his apprenticeship with Hans Finsler and Alfred Willimann at the Kunstgewerbeschule Zürich (Zurich School of Arts and Crafts), Ernst Scheidegger would henceforth embed his photographic work in an overarching concept of visual design. True to the Bauhaus tradition, this encompassed not just architectural photography, object photography, commercial photography, but also graphic design, exhibition design, book design, newspaper layouting as well as commercial and documentary filmmaking.

In 1960, Ernst Scheidegger would succeed Gotthard Schuh as image editor at the leading Swiss newspaper NZZ. According to Tobia Bezzola, Gotthard Schuh had been the first leading Swiss photographer to express disquiet at what was happening back in the mid-1930s. The forms that had made the “New Seeing” or “New Photography” of the interwar years seem an integral part of the international avant-garde were ossifying and becoming clichéd, he complained.

While conceding the importance of the schooling in “immediacy” and “precision” that had kept photography within the ambit of Constructivism and the Bauhaus during the 1920s, Gotthard Schuh felt that capturing “the whole of life in all its many facets [ … ] with intensity and spontaneity” now called for a new, more expressive, and existential sense of urgency.

By the late 1940s, established photographers such as Gotthard Schuh and Jakob Tuggener as well as younger ones such as René Groebli and Robert Frank were exemplifying this aesthetic turn within the elite of Swiss photography.

Tobia Bezzola underlines that, after World War II, the upbeat mood and faith in technology of early 1930s Constructivism seemed superficial and naive. Postwar photogarphy saw an introspective, existentialist, often darkly subjective auteur photograph emerge. Close observation sought to tease out the truth in the things of everyday life and to produce poetic distillations and staged renditions of that truth.

Ernst Scheidegger’s early photographs of Switzerland, France, Italy and the Netherlands reflected this artistic language. Those works are very different from the light, elegantly calculated and clear compositions that made his later photographs so famous. Tobia Bezzola highlights their nonchalant focus, graininess, sharp contrasts, motion blur, risky under- and over-exposure, distorted perspectives, and cut-off motifs. These early works show that the photographer was not afraid to radically unlearn everything that he had just learned during his training.

According to Tobia Bezzola, the world that Ernst Scheidegger shows us is never truly light and, if it is light, then it is dazzlingly over-exposed. The harshly drawn motifs assemble many of the topoi of the Neorealist cinema and photography of the postwar decades. They are poetic depictions of everyday life quietly observed by a photographic flaneur with a social conscience. They are seemingly incidental, rather gloomy and ponderous in tenor. They translate the shock and sense of latent menace that Swiss travelers experienced whenever they ventured into the wasteland of war-torn Europe across the border.

In the first postwar years, Ernst Scheidegger paid a spontaneous private visit to Alberto Giacometti in Paris, whom he quite by chance had gotten to know while on active duty in the Engadine in 1943. At Alberto Giacometti’s Montparnasse studio, Ernst Scheidegger shot his first series of portraits of the Swiss sculptor. After the war, he would portray him many more times, in different settings, with different goals in mind, which would make him famous too.

In the mid-1950s, the photographer began producing portraits, almost all of them commissioned. Initially, he worked for art journals such as Cahiers d’art, Verve and Du. In addition, he was involved in book projects by Peter Schifferli’s Arche-Verlag and, later, by his own publishing house. Another important client was the Galerie Maeght in Paris with its ambitious publications program. Ernst Scheidegger also made photographs for the weekend supplement of the NZZ as well as various international weeklies. Exhibition catalogs for museums would be another source of revenue. Last, but not least, he worked for the Swiss public television and, according to Tobia Bezzola, it was there that the artist portrait crystallized out as his true forte.

Ernst Scheidegger’s portraits offer strong stylistic variety and many different methods of visualization. They combine the graphic, abstract eye of his formalistic apprenticeship with Hans Finsler with his own penchant for the expressively anecdotal detail that featured so strongly in his early poetic phase. Tobia Bezzola underlines that Ernst Scheidegger complemented this stylistic repertoire with the soberly precise, pathos-free, factual reporting of a true photojournalist.

Among many other artists, Ernst Scheidegger portrayed Cuno Amiet, Varlin, Oskar Kokoschka, Le Corbusier, Max Bill, Erica Pedretti, Hans Arp, Marino Marini, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Man Ray, Germaine Richier and, most importantly, Alberto Giacometti, of whom a dozen photographs showing him and/or his atelier and/or his works are included in this great exhibition catalogue.

At the end, the book includes eleven color photographs of his 1955 visit to the city of Chandiragh — Ernst Scheidegger paid three visits to the Indian state of Punjab in the 1950s. They show half-finished and finished buildings planned by the architects Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Jane B. Drew and E. Maxwell Fry. A selection of the 1950s photographs, together with sketches and drawings by Le Corbusier, ended up in Ernst Scheidegger’s book Chandigarh 1956. It was conceived as the first publication in a series of books regarding the architectural concepts ans social concerns of modernist architects. The series was never published. In 2008-09, the photographer returned to the city and, subsequently, pubished the large-scale book Chandiragh 1956 containing over 150 color and black-and-white photographs as well as a facsimile of the original 1956 mock-up.

At the very end of the 2023 exhibition catalogue, Helen Grob, Ernst Scheidegger’s long-time life partner, shares some of her memoires in a short essay entitled “Of Fish and Friends”.

Tobia Bezzola rightly stresses that Ernst Scheidegger, unlike Philippe Halsmann, Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, never created dramatized, heroic, glamourized portraits. The Swiss was a publisher, author, graphic artist, gallerist, filmmaker, exhibition-maker and catalog designer who just happened to be adept with a camera. “Photo art” as such was never his aim.

Edited by Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv: Ernst Scheidegger: Photographer. English catalogue with contributions by Tobia Bezzola (MASI Lugano Director), Alessia Widmer (photographic historian), Philippe Büttner (Kunsthaus Zürich Conservator) and Helen Grob (Ernst Scheidegger’s long-time life partner). Order the catalogue (we earn a commission) from Amazon.com, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr, Amazon.co.uk; German edition: Amazon.de.

P.S. The cover photograph shows a Carousel at a funfair, ca. 1949.

German article about the book Ernst Scheidegger: Alberto Giacometti. Spuren einer Freundschaft. Traces of a Friendship. Bilingual English/German catalogue, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2013, 248 pages. Order the book (we earn a commission) from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review are not put between quotation marks.

Catalogue review added on October 26, 2023 at 16:37 Swiss time. Details about the different photographs in the catalogue added at 20:28.