The famous Belgian artist James Ensor (1860-1949) and his multifaceted work resist classification. Born in Ostend on the North Sea coast, he created a wild, gentle, grotesque, playful, ironic and critical pictorial cosmos. He worked as graphic artist, a draughtsman, a versatile painter, an amateur composer as well as an author.

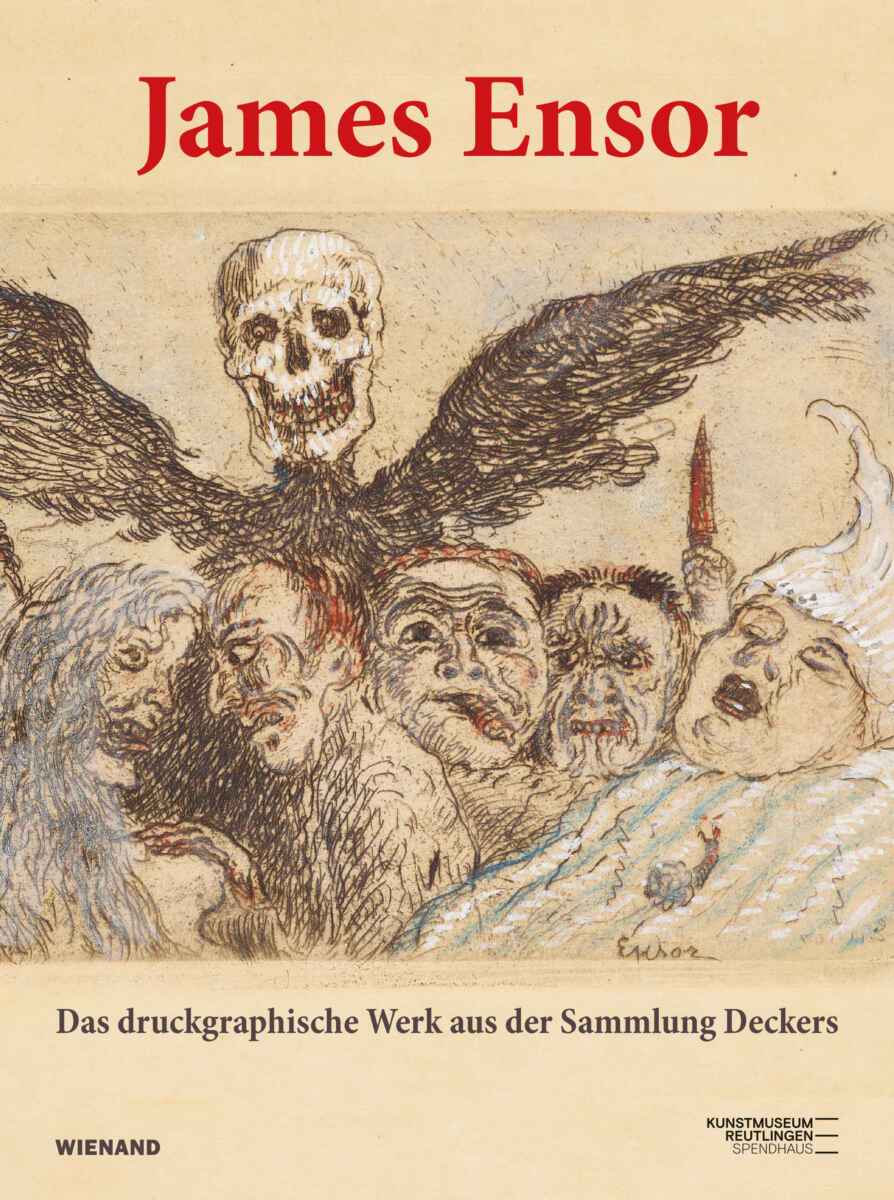

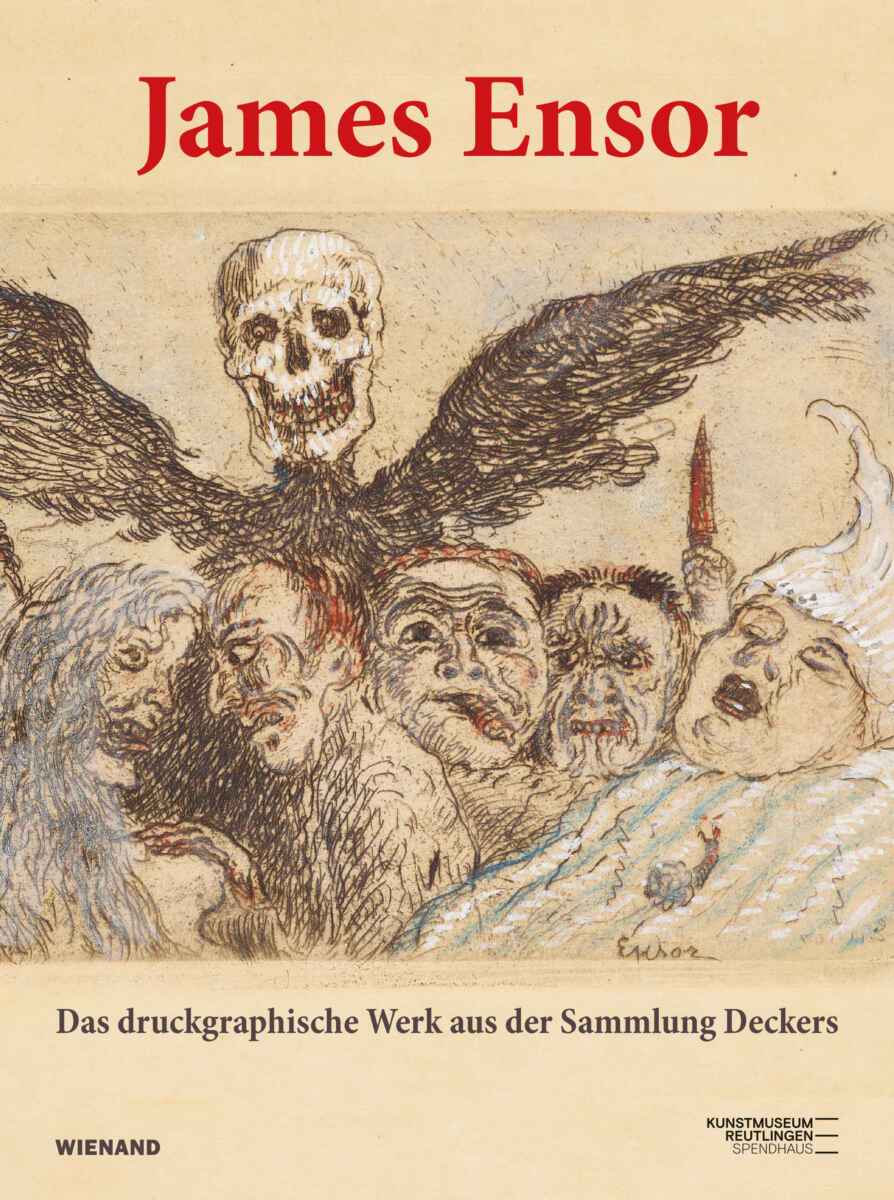

Living in Ostend like James Ensor once himself, for some twenty years, Yves and Gaétane Deckers have built up a notable collection with a focus on etchings by the artist. The first work they purchased was the etching The Cathedral (1986), reproduced on page 72 of the catalogue James Ensor: Prints from the Deckers Collection (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de), which can be admired at Kunstmuseum Reutlingen in the homonymous exhibition from February 4 until June 25, 2023.

In Ostend, the private collection of the Deckers covers almost the complete collection of James Ensor’s etchings, supplemented by even further works and letters. The Kunstmuseum Reutlingen exhibition focuses mainly on his prints and their different versions, presenting in total over 100 prints – including over 20 hand-colored examples – as well as lithographs, one painting as well as a selection of letters.

The accompanying book / catalogue (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de) contains essays by Ina Dinter (director Kunstmuseum Reutlingen) about James Ensor’s pictorial themes, work phases and forms of expression, by Cathérine Verleysen about James Ensor as a graphic artist, by Ina Dinter about James Ensor’s etching “Love Garden”, by Rainer Lawicki with a look behind the artist’s masks as well as a biography of James Ensor.

James Ensor was born In Ostend in 1860, the son of the Englishman James Frederic Ensor (1835–1887) and his wife, the Fleming Marie Catherine Louise Haegheman (1835–1915). They ran a souvenir shop together, in which James Ensor spent his childhood surrounded by exotic objects and curiosities.

Ina Dinter writes that Ensor was always a solitaire who has not found an appropriate place in art history yet, due to his unique position. She quotes the end of a text by the artist himself who wrote: “The future belongs to the loners!” He emphasized the individuality of the artist and its necessity for art. It could at the same time provide his retrospective motto. Ina Dinter describes his pictorial worlds as at the same time private and universally valid, quiet and loud, gentle and tumultuous.

Ina Dinter notes that Ensor staged himself as a great solitaire, a grand master, but at the same time his art is permeated with self-irony. According to her, his work offers two possibilities for classification: although Ensor’s oeuvre is defined by stylistic pluralism, as well as leaps forward and back, it can be either ordered according to pictorial themes or classified into chronological phases.

In Dinter stresses that there is no consistent development in James Ensor’s work because he never completely abandoned an earlier style or previous works. Instead, he repeated and varied them, either in the form of direct copies of his own works in an updated coloring or as individual motifs like masks, nymphs, or still-life objects. She underlines that James Ensor always remained true to himself with this special kind of self-referentiality. He never entirely forfeited a work phase.

James Ensor wrote: “My art has never stopped developing, liberating itself, abandoning the beaten paths, the norms, the cliches. I have tried to escape from my own. Painting must change itself, transform itself, renew, err, and find itself again, simply remain lively and sensitive. The light changes at every hour and every day.”

According to Ina Dinter, James Ensor’s oeuvre can be divided into three phases: His early, thematically diverse work, which began with his first attempts at painting in the 1870s, includes figurative paintings, figures from the Bible and mythology, works referring to a literary model, nude studies during his academic training, self-portraits, landscapes, harbor and city views, as well as, from 1880 on, interiors, especially with women, and still lifes. His early work is often marked by a broad style with dark hues. Unlike the image descriptions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as unlike the texts written later on the basis of these, James Ensor’s early paintings are not as dark as they might appear, particularly in older reproductions, all according to Ina Dinter.

She describes his early work as “realistic” for two reasons: first, James Ensor oriented himself stylistically to Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) and to Belgian realists and naturalists like Guillaume Vogels (1836–1896), Hippolyte Boulenger (1837–1874), Louis Artan (1837–1890) and Louis Dubois (1830–1880), whose style is often referred to as “Tachism.” At the same time, his early works feature figures representative of the rural population, such as fishermen, working women, poachers, alcoholics, or rowers.

Ina Dinter writes that it has been suggested that Ensor’s version of the grotesque, which mixes with the fantastic in the middle phase of his work, is already discernible in his early work. A clear incursion of the fantastic and a change of coloring, as well as stylistic versatility resulted in James Ensor surpassing his early work phase in the early 1880s. In the mid-1880s, the artist himself used the generic term “fantastic”.

Landscapes, still lifes, interiors, portraits and self-portraits were now joined by new pictorial motifs, of which the mask remains one of the most familiar. James Ensor mostly referred to the Flemish masks of the traditional Ostend carnival as well as to the Asian masks sold in the souvenir shop of his parents, other masked figures originate in turn from the artist’s imagination. Ina Dinter stresses that he only painted anthropomorphic masks.

Emile Verhaeren (1855–1916) was the first to refer to Ensor as the “painter of masks” in his monograph, which was published in 1908. Ina Dinter writes that James Ensor preferred to refer to himself as the “painter of masks and the sea”. She mentions that another pictorial theme in his late nineteenth century work was death—often captured satirically. His most used motifs included a skeleton or a skull clad in rags, surrounded by aggressive mask figures. Other new subjects included mortality, the city, the masses, biblical narratives as well as sociocritical themes such as prostitution, gambling, jurisprudence, medical care and the authorities. Fantastic creatures such as monsters, chimeras, devils and witches appeared in his works. Alongside these new subjects, James Ensor modified his painting style and coloring in his second work phase. He increasingly dispensed with details and internal contours, instead now allowing the intrinsic value of the color to dominate in relation to its representational value. He predominantly used unmixed colors which caused an expressive image effect, especially in the mask paintings.

Light and color also play a vital role in Ensor’s late work, according to Ina Dinter. While the paintings in the first work phase are held in dark hues and those of the second phase are primarily painted in garish colors, white and colors mixed with white now dominate in the third phase. Thematically, James Ensor’s late work, which commenced around 1910, demonstrates less tension and struggle than his earlier works. Ina Dinter writes that even the masks seem less threatening. The subject of the macabre does not disappear from his work, but it does recede somewhat into the background. James Ensor now focuses on women and eroticism. Dancing ballerinas and nymphs are among his new favorites. He increasingly blurs the genre boundaries. They are made even more obscure by unusual coloring. The artist develops a new type of self-portrait in the 1930s, in which he surrounds himself with attributes of his art: flowers, shells, fruit, his coat of arms, dancers, nymphs, sirens, love gardens, monsters, masks and mask figures, musical notes, rainbows, and light. According to Ina Dinter, in this way, James Ensor represents himself not merely as an artist, but also as the author of his works.

In 1934, James Ensor introduces a new type of bust. In a total of eight works, he presents his head either frontally, slightly turned to the side, in semi-profile or in profile. In the late self-portraits, he takes stock of his artistic production and makes clear qua repetition and recombination how closely his pictorial motifs and how closely art and life are linked for him. His self-portraits virtually emphasize the repeatability of art.

This and much more you can discover in the catalogue edited by Ina Dinter: James Ensor: Prints from the Decker Collection. Kunstmuseum Reutlingen, Wienand Verlag, February 2023, paperback, 170 pages with 76 color and 3 b/w illustrations, 27,5 cm x 20,5 cm. Order the bilingual book (German|English) from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Exhibition: Kunstmuseum Reutlingen from February 4 until June 25, 2023.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations from the catalogue James Ensor: Prints from the Deckers Collection (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de) are not always put between quotation marks.

Book / Catalogue review added on March 2, 2023 at 15:39 German time.