Biography and book review

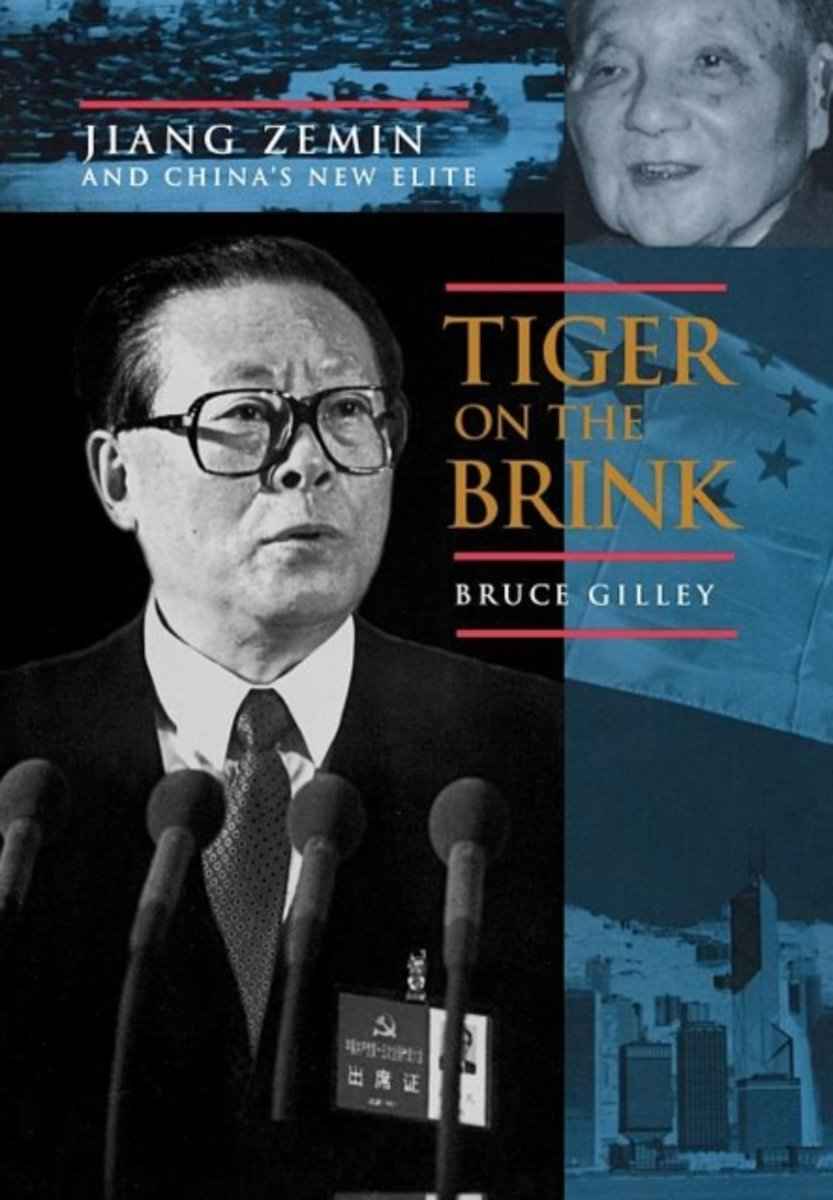

Bruce Gilley: Tiger on the Brink. Jiang Zemin and China’s New Elite, Berkeley and Los Angeles, London, University of California Press, 1998, 395 S. Order the book from Amazon.com. Book review:

President and Communist party chairman Jiang Zemin was born on August 17, 1926, in Yangzhou, as the third of five children of a writer and electrician and a peasant mother. His father played no important role in his life. After his uncle’s death, he was adopted by the uncle’s wife. They were intellectuals. Jiang Zemin went to Shanghai in 1945 in order to become an engineer. Ironically, his Yangzhou-accent made him an outsider in the cosmopolitan capital, today Jiang is known as “the man from Shanghai”. English played an important role in his studies. In 1946 he joined the Communist party – but did not try to begin a party career. In 1949 he married a friend from school – who had no influence on his career. He even lived apart from her for decades. In 1949, Jiang took over an important post in the industrial sector. The campaign against the “rightists” in the 1950s did not affect him. In 1955 he was sent to Russia by his Changchun-automobile company for four months. In 1956 he returned to China and rose to the post of vice-director in his company. During the cultural revolution, Jiang was neither a fanatic nor did he speak up against the party line. At the end of the 1960s he was under attack from the Red Guards but his “heroic” contribution to the industrialization and his moderate lifestyle saved him from persecution. His career came to a standstill for three years.

Jiangs comeback started in 1970 in the elite school of the First Machine Building department. Then he went to Rumania for two years and after his return to China he rose to the post of vice-director of the Foreign Affairs Bureau of his department in 1974. Another two years later, he became its director. After a year in Shanghai he returned to Beijing. In 1978 Wang Daohan was rehabilitated and Deng Xiaoping was in favor of economic reform. Jiang’s career got a boost and travels abroad convinced him of the reform path as the right way to follow. A free exchange zone in Ireland and Singapore’s Jurong industrial park made him propose – together with other members of the delegation – the creation of special economic zones in China. His speech in November 1981 in front of the Permanent Committee of the National People’s Congress convinced its majority. In the early 1980s, the reformers Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang dominated the party. Jiang could rise up in the party’s hierarchy. When Wang Daohan stepped down as major of Shanghai in 1985, he recommended Jiang as his successor. In 1986 Jiang managed to please everybody during the students protests. He did not crack down on them, although he did not appreciate their actions. The press ignored the protests. As a politician, Jiang always knew where to stand. He had a sixth sense for anticipating future developments. Jiang showed his conservative face and, according to Gilley, if it was not for Hu Yaobang, he would have taken more severe actions against the students. But he cracked down on the press which, since then, has never ever dared to attack him again.

In 1987 Jiang become part of the 15-member politburo, China’s center of power, and took over as party chairman in Shanghai. Zhu Rongji became his successor as Shanghai’s major. The two formed an efficient team, modernizing the country, letting foreign direct investments flow in and battling against red tape. Still, Jiang kept an image as “all show and no substance”, “panda bear” and “flower pot”. He was said to turn with the wind. In 1989 Jiang and others in Shanghai hindered the publication of the liberal World Economic Herald. Zhao thought the reform process would be endangered by this action. Again, Jiang anticipated Zhao’s vanishing influence. The power struggle between Zhao and Li Peng was only decided on May 17, 1989, in Deng’s residence. No party elder spoke on Zhao’s behalf against the introduction of military rule (installed on May 20). Jiang was among the first local party chiefs to support this decision. At the same time, he did not use force in Shanghai, already thinking about future judgments on such an action (according to Gilley).

Deng chose Jiang as Zhao’s successor because he thought of him as a man in favor of reform who could also show a tough side if necessary (if the party power monopoly was in danger). Two thirds of Bruce Gilley’s biography of Jiang Zemin concentrate on the years after 1989. This is not the place to enter into all these details. The biography has its merits regarding the account of Jiang Zemin’s life, but it is too mild in its judgment of the Chinese general secretary and president. One hardly gets to know and understand that he is the leader of a communist party which still tries to hold on to its power monopoly and does not respect Western standards regarding political, economic, religious, cultural and moral standards. Jiang Zemin appears too much to be a president just like a Western leader. Only here and there does one learn that e.g. in 1996 358,000 people were arrested and thousands killed in a campaign against corruption and crime. For a second edition: a chronology would be helpful.

Willy Wo-Lap Lam: The Era of Jiang Zemin, Prentice Hall, 1999, 464 p. Order the book from Amazon.com. Book review:

Willy Wo-Lap Lam is associate Editor and China Editor of the South China Morning Post, Hong Kong’s leading newspaper. He is responsible for SCMP’s coverage of China and China-Hong Kong relations. He is also an author and researcher. His book The Era of Jiang Zemin is probably the best account on contemporary China. It is not a narrow biography of its leader (from Jiang’s accession to the post as China’s Communist Party General Secretary in 1989 to mid-1998), but a broad analysis of key figures and leadership in China, of their political, economic and social ideas and policies. Willy Wo-Lap Lam has interviewed a great number of high ranking Communist party members and researchers, businessmen as well as diplomats. He describes Jiang Zemin as a conservative communist leader who tries to preserve the party’s power monopoly and hundreds of “key” state enterprises, although the Asian crisis made them take further steps in the direction of private enterprises. Willy Wo-Lap Lam also focuses on corruption, the one-China policy towards Taiwan, power struggles within the Communist party, the role of the People’s Liberation Army and Jiang’s obsession with his place in history – the Hong-Kong handover is one keyword, Taiwan is another. Willy Wo-Lap Lam describes in detail the 1995-96 Taiwan Straits crisis. Zemin’s rise to power is, according to him, due to his ability to please everybody, to have no enemies. He also had the luck that most of the party elders, who had ruined the careers of his predecessors, the reformers Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, were too old (or even dead) in the mid 1990s to pose a threat to him anymore. For Willy Wo-Lap Lam, Jiang Zemin is a man without qualities who knows how to muddle-through but who has no visions and no masterplan for China’s future. As a survival tactic and later a tactic in order to rise to power, this may have been helpful, even necessary, but today, it is a threat for China’s future.