Catalogue and exhibition review. On display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City until February 2, 2016

The last, great exhibition and catalogue with sculptures by Pablo Picasso (I have seen) took place at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris in the year 2000 (review), curated by Werner Spies.

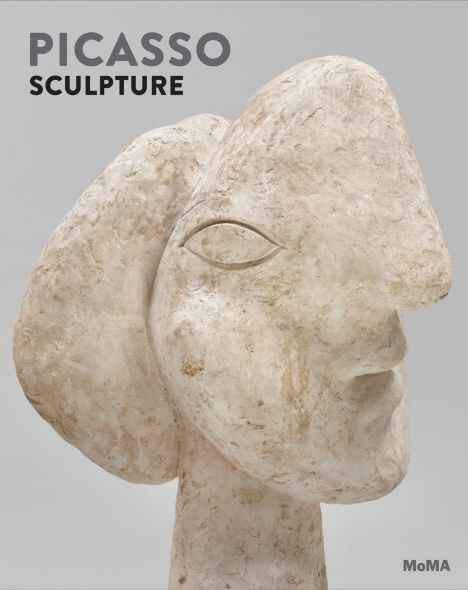

On September 14, 2015 the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City opened its great Picasso Sculpture exhibition, a must for any art lover. Some 150 sculptures by Pablo Picasso will be on display until February 2, 2016 (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de).

It is the largest exhibition with sculptures by Pablo Picasso in the United States since 1967. That show took also place at the MoMA.

The present exhibition is a full-scale survey of Picasso’s sculptures that was largely made possible thanks to the MoMA’s collaboration with the Musée national Picasso in Paris, which houses the world’s largest collection of Picasso’s sculptures. The French museum contributed 50 sculptures to the Picasso Sculpture show in New York.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) kept most sculptures to himself during his lifetime. Therefore, an important number of them entered the founding collection of the Musée Picasso in Paris following the settlement of his estate.

The curators of the New York exhibtion, Ann Temkin and Anne Umland, try to rewrite the history of Picasso’s sculptures: “… instead of asking why and how the sculptures remained a well-kept secret, we decided to investigate the possibility that these objects actually did have the dynamic histories far more lively and complicated than the myth of secrets should suggest.”

A myth? That is a bit too strong a word. The curators themselves mention in the catalogue that the first book dedicated to Picasso’s sculptures was only published in 1949 by the artist’s longtime art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who opened his text with a defensive remark, letting the readers know that the sculptures were more than Picasso’s “violon d’Ingres”, a French expression for an artist’s hobby.

The first comprehensive exhibition of Picasso’s sculptures was only organized in 1966, when the artist was already 85 years old. It took place at the Petit Palais in Paris and assembled the works he had kept with himself.

The catalogue raisonné of Picasso’s sculptures was only published by Werner Spies and Christine Piot in 1971, roughly two years before the artist’s death. Picasso himself reportedly greeted the publication as the record of “an unknown civilization”.

Ann Temkin and Anne Umland mention all of this in their catalogue and still come to the conclusion that the roughly 700 sculptures Picasso made played a role that is “remarkably rich”. They argue for their “visibility and impact throughout the course of his long lifetime.”

The curators explain that, as a child, Pablo Picasso “made cut-paper silhouettes that prefigure his Cubist constructions as well as his post-World War II sheet metal cutouts”. As a young boy, he modeled and painted crèche figurines which “presage an interest in ceramics and in polychromy”.

Ann Temkin and Anne Umland come to the conclusion that “these protosculptural pastimes have roots in craft traditions as opposed to the history of Western sculpture.” According to the curators, “for Picasso sculpture would always be something deeply personal, highly improvisatory, often intimate in scale, and encompassing a vast range of styles, materials, and techniques.”

The authors write that “Picasso’s first true sculpture” was Seated Woman (1902), made when he was 20 of unfired clay in the Barcelona studio of Emili Fontbona, one of his many sculptor friends. He learned about sculpture from his friends “rather than from any formal course of study.” After all, he was trained as a painter, not as a sculptor. And from the start, he disregarded tradition in his sculptural work, redefining it by that approach.

Regarding his student years, Ann Temkin and Anne Umland mention that if he should have tried his hand at sculpting during those years, “no traces remain of his efforts”.

Picasso definitively moved to Paris in 1904. He continued to produce sculptures, although only sporadically. Until late 1909, he made fewer than 30 sculptures. And for the following 3 years, he made none at all.

The early sculptures show a large variety of influences, including “the ceramics and woodcarvings of Paul Gauguin; Edgar Degas‘ early, naturalistic figures; the impressionistic surfaces of Auguste Rodin and Medardo Rosso; and ancient Iberian stone carvings.”

The authors emphasize that “most important” was the artist’s “discovery of African and Oceanic sculpture, which he studied with particular intensity during the summer of 1907.” A visit to the African art collection at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris, suggested by his friend André Derain, “was immediate and decisive” and led to his masterpiece, the proto-Cubist Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907.

In their 20-page catalogue essay, Ann Temkin and Anne Umland examine all the artists periods. The study of Pablo Picasso’s sculptural oeuvre brings them to the conclusion that he is less “the individualistic Romantic genius” than a man who collaborated “intensely and willingly” with “fellow artists and artisans” during his entire life. The sculptures also reveal his attachment to the “even amateurish object”. The authors question the concept of “the masterpiece” as “the foremost shaper of an artist’s identity.” They argue that “Picasso’s sculpture stands apart from the paintings and works on paper in the remarkable efficiency with which it accomplished its many reinventions and redefinitions.” For Ann Temkin, Anne Umland, “the sculpture reveals itself as a quintessential rather than exceptional aspect of Picasso the artist.”

In addition, the richly illustrated catalogue subsequently offers a documented chronology from 1902 until Picasso’s death in 1973. It is an important book for anyone who thinks like me that Picasso’s sculptures are the real highlight of his artistic output, full of invention and experimentation, leading to the creation of many masterpieces.

The Picasso exhibition occupies the entire fourth floor galleries of the MoMA, allowing the 149 sculptures to be viewed fully in the round. In addition, one gallery features 25 photographs of Picasso’s sculptures taken by the eminent French photographer Brassaï (1899-1984). The two artists first met in Paris in December 1932 at Picasso’s studio at rue La Boétie. At the time, Brassaï had been commissioned by the editors of the Surrealist magazine Minotaure to photograph two of the Spaniards studios. From that shoot onwards, Brassaï became Picasso’s photographer of choice when it came to take pictures of his three-dimensional works.

Regarding New York and Picasso’s sculptures, let’s not forget to mention that the artist made some 120 sheet metal sculptures within 18 months. Towards the end of his life, some of Picasso’s dreams of monumentally scaled works came true. One example is the 20-foot-tall Sylvette, one of many sheet metal sculptures that became outdoor works. In 1968, Sylvette was erected outside a New York University housing complex on Bleeker Street and La Guardia Place, where it can be admired (free of charge) until today.

A visit of the Museum of Modern Art in New York is mandatory for any art lover. After the end of the Picasso Sculpture exhibition, don’t forget to pay a visit to the outstanding, freshly-renovated Musée Picasso in Paris, which offers more than the 50 sculptures currently on display at the MoMA.

Ann Temkin, Anne Umland: Picasso Sculpture. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2015, 320 pages. Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Review article added on September 22, 2015 at 17:22 CET.