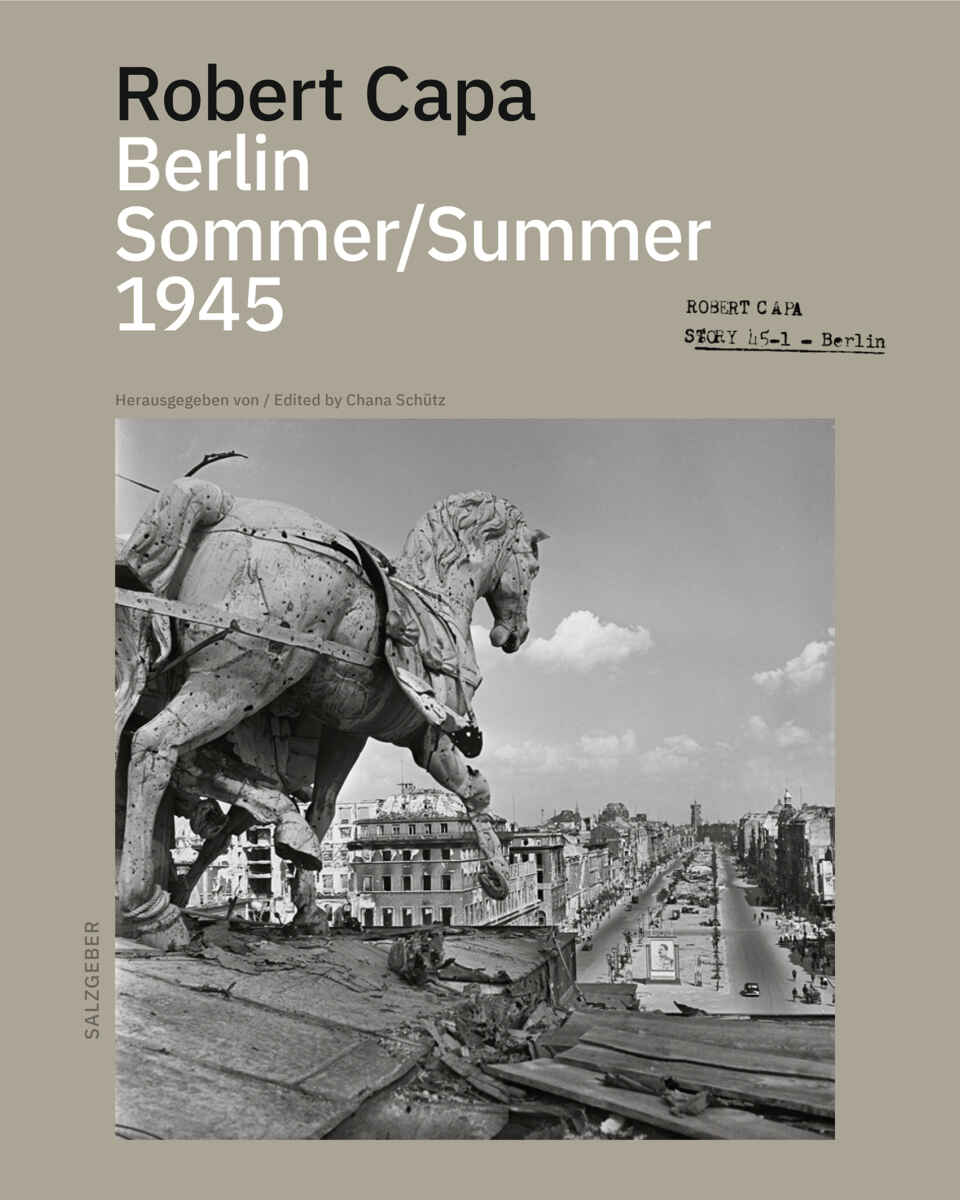

In the summer of 1945, the famous war photographer Robert Capa documented the German capital, bombed to the ground. From September 9, 2020 until April 30, 2021 a selection of 120 of those photos is on display at New Synagogue Berlin — Centrum Judaicum Foundation. The exhibition was mounted by Chana Schütz in cooperation with the Robert Capa Archive at the International Center of Photography in New York. The show entitled Robert Capa: Berlin Summer 1945 is worth a visit.

This article is based on the impressions of my exhibition visit and on the catalogue of the same title (Amazon.de, Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr). The book contains some 72 illustrations, including a selection of 56 of the 500 Berlin vintage photogaphs by Robert Capa from the summer of 1945 as well as photos of his Life magazine stories published in 1945.

A few remarks abou the life and career of Robert Capa

Robert Capa was born Endré Ernö Friedmann on October 22, 1913 in Budapest, the second child of parents who ran a fashion store in Pest from 1910 until 1931. That year he was arrested during a demonstration against dictator Admiral Horthy — an admiral with no fleet. Incidentally, the current, illiberal Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban sometimes offers strange praise for Horthy.

Back to Robert Capa, who fled via Vienna to Berlin in 1931 where he enrolled in the winter semester 1931/32 at the German University of Politics (Deutsche Hochschule für Politik). Without money, he was soon forced to abandon his studies and work as an errand boy and laboratory assistant at Simon Guttman’s Dephot (Deutscher Photodienst).

In 1932-33, under Simon Guttmann, he learned the trade of the photojournalist and reporter. Equipped with a Leica, he was commissioned by Dephot to shoot a first story in Copenhagen: “Trotzky Steps up to the Lectern”, published in the illustrated magazine Der Welt-Spiegel in December 1932. After the Nazis came to power the following year, Simon Guttman helped André Friedmann to flee to Paris, via Munich and Vienna. In the French capital, he worked as a freelance photographer and, in 1934, met the love of his life, the German-Jewish communist Gerta Pohorylle (1910-1937). They both changed their names to Gerda Taro and Robert Capa.

Together with David Seymour (aka Chim) and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa went to Spain to document the Civil War. Their photo reports reached mass audiences in magazines such as Life in the United States, Vu, Regard and Ce Soir in France as well as in the “Aryanized” Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung in Germany.

Robert Capa rose to fame with a photo now called “The Falling Soldier”. According to evidence discovered in more recent years, the photo was staged. But that was pretty common at that time.

On July 26, 1937 Gerda Taro tragically died in Spain when a Republican tank accidentally hit General Walter’s car.

Robert Capa made many other iconic images, especially during World War Two. Let’s just mention his D-Day photographs, taken on June 6, 1944 when he landed with the first Allied troops on Omaha Beach on the Normandy coast.

Let’s jump to 1945. Robert Capa shot two of the photographs which marked the end of World War II in Europe, one showing US private Raymond J. Bowman, shot by Germans in Leipzig by Germans on April 18, 1945 the other showing GI Robert Strickland raising his arm in a sarcastic Hitler salute on April 20, 1945 at the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg. Both photos were published in Life on May 14, 1945.

Robert Capa: Berlin Summer 1945

In 1933 Berlin’s Jewish population had been 160,000. Between 1941 and 1945, over 54,000 Jews were deported from the German capital and murdered. When the Red Army liberated Berlin, only 7,000 Jews were left in a city that was once home to one of the largest Jewish communities.

In August and September 1945, Life sent Robert Capa to Berlin for two reports. One was about the black market near the Brandenburg gate, published on September 10 under the title “Black Markets Boom in Berlin: Red Army men are biggest buyers”. The other one was about the first Jewish New Year’s service (Rosh Hashanah) after the liberation from the Nazis, published on October 8, 1945 under the headline “Jewish New Year”.

As mentioned above, during his summer stay in Berlin, Robert Capa shot some 500 photographs. For the first time since 1936, he did not have to cover a war. The pictures do not deliver the kind of intensely emotional or physical story Capa was known for. Nevertheless, they mark the end of his nine-year coverage of the fight against fascism.

After photographing jubilant victories in Naples, Rome and Paris, he arrived in Berlin at an anticlimax. He found a city in ruins. Robert Capa pointed his camera at buildings. But the resulting images are never topographic, no more inventory of architectural destruction. They are always about the human component of the city. Even the the photo seems to be about a building, there is always a figure in the frame, writes Cynthia Young in the catalogue. His images are not imbued with poignancy or hope. He does not work for a good composition. Most of his work is quick, done at a distance. He probably knew that most of his work would never be published. In one photo, he includes some dark humor with a fallen angel shown in the foreground. Some of his strongest images are about rubble women, the famous Trümmerfrauen, who worked collectively to clear the ruins from the German cities, although one should add that more recent studies show that their work is overrated, some images (not by Capa) seem to be staged, for instance with women in improper shoes and clothes smiling in the camera. Capa’s pictures show little compassion or appreciation for their work, writes Cynthia Young.

Robert Capa’s images of the Spanish Civil War are imbued with his desire to show the agony and struggle for victory, whereas in his Berlin photos from the summer of 1945, the emotion is muted. There are no individual portraits, not does he let his subjects observe of engage with him. He keeps a distance.

I would slightly disagree with the above, noting that the photos taken at The Femina dance café in the American sector show American and Soviet soldiers drinking, dining and partying with German “Fräuleins”, having a good time. They are intimate. As for the rest of the photos, they show indeed Capa keeping an unusal distance, most likely because he had sympathized with the Left in Spain and had little sympathy left for the Germans. Interestingly, The Femina dance café (Femina Tanzpalast) had been opened by the Jewish entrepreneuer Heinrich Liemann in 1929. It was a new style place with a marble entrance hall, several bars, dance bands and tube mail delivered by girls in uniform, table telephones and a dance floor that could be raisend. The huge ballroom in a separate rear building had two circles and skylights. In 1933 Liemann, his wife and children were forced into exile. Hermann Liemann died a poor man in London in 1940. This and more info about the 1945 photographs you can find in the catalogue (Amazon.de, Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr).

Robert Capa does not explore the division of Berlin into four zones of occupation. He just shows large images of Stalin in the Soviet sector. And he spent significant film at a nightclub filled with Allied and a few Soviet soldiers dining and dancing with German women. One could have mentioned here that tens of thousands of German women were raped in Berlin alone by mainly Soviet soldiers at the end of the war. Prominent is the case of the wife of former chancellor Helmut Kohl, Hannelore. At the age of 12, she was gangraped and treated brutally more than once by Soviet soldiers. But that is another story.

On the other hand, Robert Capa’s images of the 1945 Rosh Hashanah service made for Life are intimate, showing a level of genuine curiosity and confidence. The photographer himself had never been religious and, therefore, was not familiar with the rites he observed, notes Cynthia Young.

Assignments for a corporate magazine such as Life was not the kind of work Robert Capa excelled in, nor did they represent they kind of photographer he wanted to be. In fact, this was the last time he worked for Life before he left the staff of the magazine.

Upon Capa’s idea, in Paris in 1947, Robert Capa, David “Chim” Seymour, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and William Vandivert, Rita Vandivert and Maria Eisner founded the famous, independent Magnum photo agency, one of the first photographic cooperatives.

Robert Capa died on May 25, 1954. Life had sent him to Vietnam to report on the war. At the delta of the Red River, he stepped on a landmine. He was only 40 years old.

These are obviously only a few take-aways from a book about an exhibition you should discover.

Robert Capa: Berlin Summer 1945. Edited by Chana Schütz for New Synagogue Berlin — Centrum Judaicum Foundation. Bilingual book in German and English, Salzgeber Buchverlage Berlin, 2020, 160 pages with contributions by 7 authors and 72 illustrations, including 56 vintage photographs by Robert Capa as well as numerous photos of newspaper and magazine stories by the legendary photographer. Paperback, 24 x 29.9 cm. Order the book from Amazon.de, Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this book review are not put between quotation marks.

Exhibition and catalogue review added on September 24, 2020 at 18:46 Berlin time.