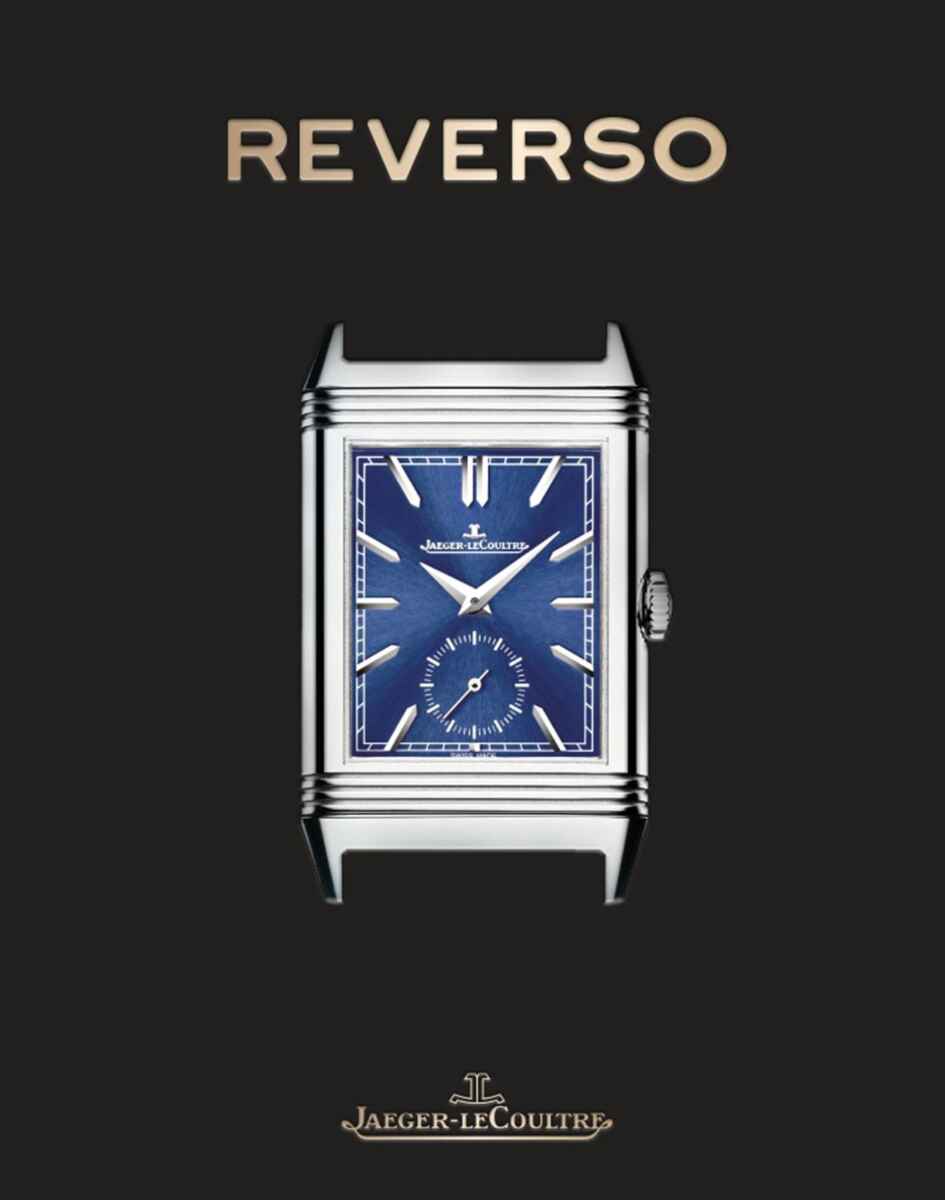

When I was about to finish university (a long time ago), I offered myself a Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, the iconic Art Deco watch created in 1931 as a purpose built piece to withstand the rigours of a polo match. In 2021 the well-known British historian and journalist Nicholas Foulkes has published his book Jaeger Le-Coultre: Reverso with Assouline (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr) and in close collaboration with the Swiss watchmaker.

Nicholas Foulkes explores the social milieu and cultural changes that provided the backdrop to the creation of the Reverso and, later, its continued reinvention. In addition, he tells us the fascinating story of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s founders, their inventions and much more.

At the beginning of the book (pages 12 and 13), you can find a photograph of a Reverso, set aside a picture of the entrance of the Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes 1925, which decades later coined the term Art Deco. And indeed, the entrance looks like a Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso!

The 1925 show in Paris represented a break with past grand exhibitions. The modern world was presented in a new way. Rather than ponderous expressions of patriotism in a museum-like setting, the exhibits were displayed in context. They were no longer abstract units of production but object to aspire to. It was not so much an exhibition as an entirely new, modern way of life just waiting to be lived.

From the turn of the century until the 1920s, new technologies such as the car, the airplane and electronic mass media conquered the world. The wristwatch had emerged out of nowhere; in fact, out of military cercles where men wore them. By the late 19th century, they were accepted as pieces of jewellery alongside brooch and pendant watches. By the winter of 1930, wristwatches accounted for half of all Swiss watch exports; from then on, the pocket watch would enter a steep and irreversible decline.

In 1895 Oscar Wilde confidently expressed that ‘No gentleman ever takes exercise.’ But three decades later, attitudes to physical fitness had changed. Nicholas Foulkes writes that exercise was not only acceptable, it was fashionable. The surge in the popularity of sportswear such as the tennis or polo shirt (René Lacoste!) coincided with the rise of Art Deco.

In 1930 the Swiss businessman César de Trey was made aware during a business trip to British India that further development was required before the wristwatch could match the purposeful practicality of the polo shirt. Broken glasses were common during polo matches.

Nicholas Foulkes quotes the 1992-book by the horological historian Manfred Fritz: Reverso: The Living Legend, Edition Braus: ‘De Trey’s British friends knew he had by now switched from dentures to watches, and so they innocently asked him whether it might be possible to make a watch that could be covered or possibly even turned over to protect the fragile glass during the game. The word “turn

over” stuck in the mind of their Swiss guest and watch enthusiast like an arrow in its target.’ Soon afterwards, César de Trey registered the name Reverso, Latin for ‘I turn’.

César de Trey partnered with the Paris watchmaker to the French navy Edmond Jaeger and his partner Gustave Delage as well as the Swiss watchmaker Jacques David LeCoultre; the LeCoultre company was famous notably for providing the ultra-thin movements for the couteau pocket watches by the luxury jeweller Cartier as well as the clocks for carmakers such as Cadillac, Packard and later Bentley.

The de Trey, Delage, Jaeger and LeCoultre cooperation led to the creation of the company Jaeger-LeCoultre in 1937. In 1931 already, the men asked René-Alfred Chauvot, according to Foulkes a French engineer working for LeCoultre, to develop the original, reversible Reverso watchcase that would protect the glass during polo games. According to Foulkes, this was based on the patent application of the same year by César de Trey for ‘a watch capable of sliding in its support and being completely turned over.’

Manfred Fritz underlines the role of the French industrial designer René-Alfred Chauvot more than Foulkes. Based on Manfred Fritz’s book and Jaeger-LeCoultre’s website, one can conclude that César de Trey had the original idea of a case that could flip over. But it was developed by Chauvot. The Paris patent office received the application to register the invention on March 4, 1931. César de Trey bought the rights to Chauvot’s design in July 1931 and registered the Reverso name in November of that year.

Nicholas Foulkes writes that the original design, with its Breguet hands and Arabic numerals, looked arguably more feminine, more Belle Époque than Art Déco. Between the patent application and the manufacture of the first models, the case lengthened, its elegance enhanced by the addition of a trio of sober godrons at the top and bottom that subtly elongated the case, imparting something of the appealing ratio of the Golden Section, while drawing the eye to the comparatively large plane of the watch glass. Moreover, many early models dispensed with numerals in favour of unadorned baton indices paired with sword hands. The transformation into an up-to-date Deco design was thus complete, and yet, these modern designs evoked a timeless beauty.

Nicholas Foulkes underlines the Reverso’s rational quality that was in line with the form-follows-function ethos that informed much of Deco design, while the aesthetic restraint and linear decoration could have been taken from an architectural textbook of the time. He also notes that the (early) Reverso watches — like my much later one — were frequently made in the industrially correct material of steel rather than traditional gold or silver. The Reverso’s value lay not in the costliness of its materials and lavishness of its embellishments but in the ingenuity and intricacy of its engineering.

Interestingly, early on, Reverso cases were sold to other famous watchmakers. Between December 1931 and April 1932, eight Reverso cases were sold to the Patek Philippe factory. This operation was carried out with the agreement of César de Trey, who had already registered the name “Reverso” as a trademark, and Jacques-David LeCoultre, then one of the directors of Patek Philippe.’ During this period, Cartier, Hamilton, Favre Leuba and Vacheron Constantin also sold Reversos’.

After the Second World War, the Reverso was forgotten until Art Deco came back into fashion. It was Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Italian representative, Giorgio Corvo, who bought the remaining 200 empty Reverso cases in Le Sentier, at the watchmaker’s headquarters. Apparently, the Manufacture called back three times to confirm the order. Corvo overcame all obstacles, had the watches made and sold the 200 new Reversos within a month. Immediately, the Italien asked for more to be produced. Finally, Jaeger-LeCoultre woke up and, in 1975, the Reverso returned to the market. It was the quartz age. According to Nicholas Foulkes, the Swiss watchmaker owns its very survival to iconic Art Deco models.

Subsequently, the Reverso was improved by the company’s case designer Daniel Wild. The new version was launched in 1985 and was a truly waterproof watch with a better functioning turn over mechanism in a newly designed reversible case, while staying true to the original exterior design. Foulkes stresses that, compared to the original Chauvot design’s twenty-three components, the Wild redesign of the Reverso comprised fifty-five parts. It was completely different yet looked almost identical.

To my knowledge the most important auction to this day of vintage Jaeger-LeCoultre watches was organized by Artcurial in Paris in 2011, including many Reverso models, notably from 1931 to 1940, a dream come true for any collector; it was the 90th birthday of the iconic Art Deco watch.

In May 2015, Antiquorum in Geneva auctioned off General Douglas MacArthur’s Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso for 70,000 Swiss francs ($75,000); I have the AFP story still on my laptop. The model in question is still being manufactured today. Nicholas Foulkes does not mention the 2011 Artcurial auction, but offers the Douglas MacArthur story in detail. He puts the auction result at $87,500; the AFP result probably did not include the buyers premium and/or taxes. Foulkes rightly writes that the price almost reached nine times it’s low estimate. Indeed, Antiquorum had estimated it at 10,000 to 20,000 Swiss Francs. From Foulkes book I learned that the Douglas MacArthur Reverso is now part of the collection of the watchmaker Jaeger-LeCoultre.

These are just a few highlights from a detailed text about an Art Deco icon. Order the English, richly illustrated book by Nicholas Foulkes Jaeger-LeCoultre: Reverso (Assouline, 2021, 252 pages) from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.de, Amazon.fr.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations from the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso (Assouline) book reviewed here are not put between quotation marks.

Book review added on July 5, 2021 at 19:00 Swiss time.