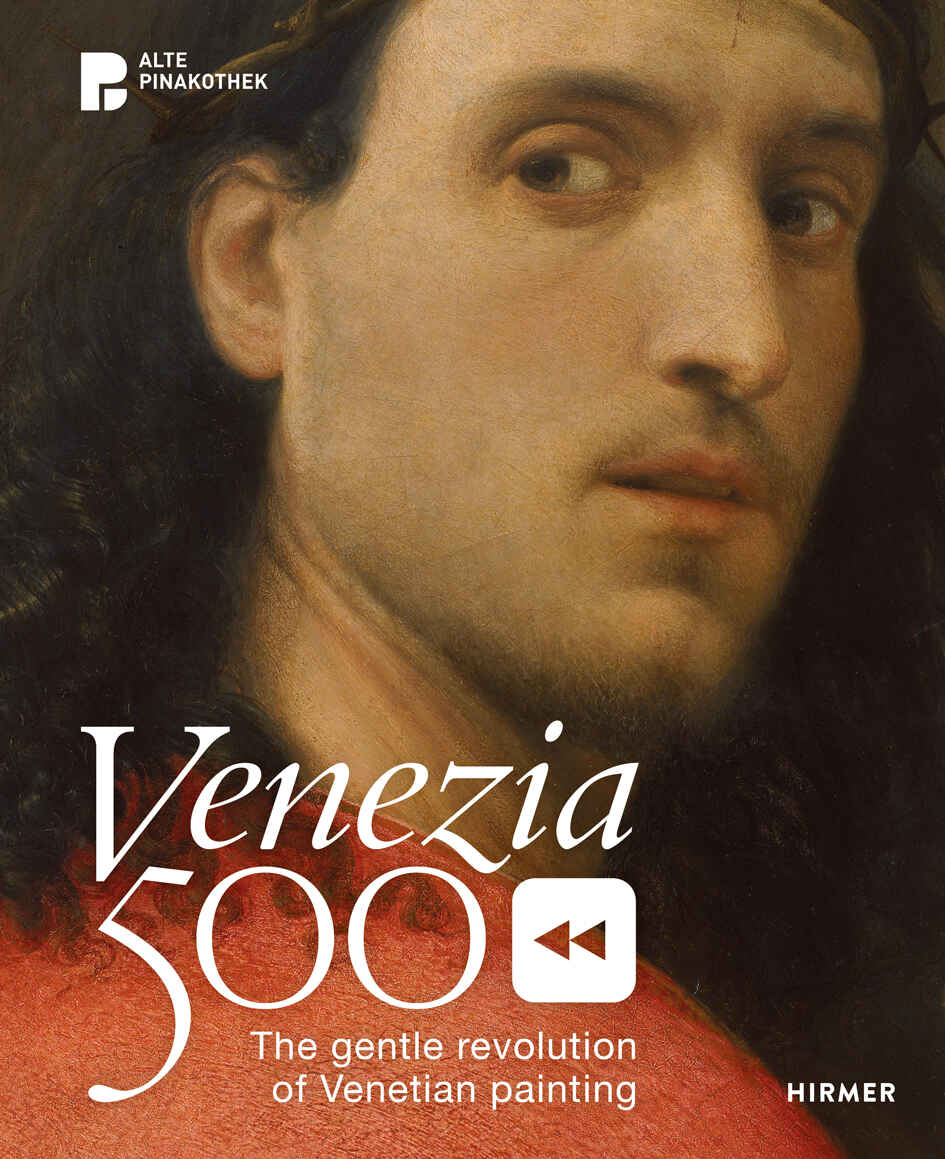

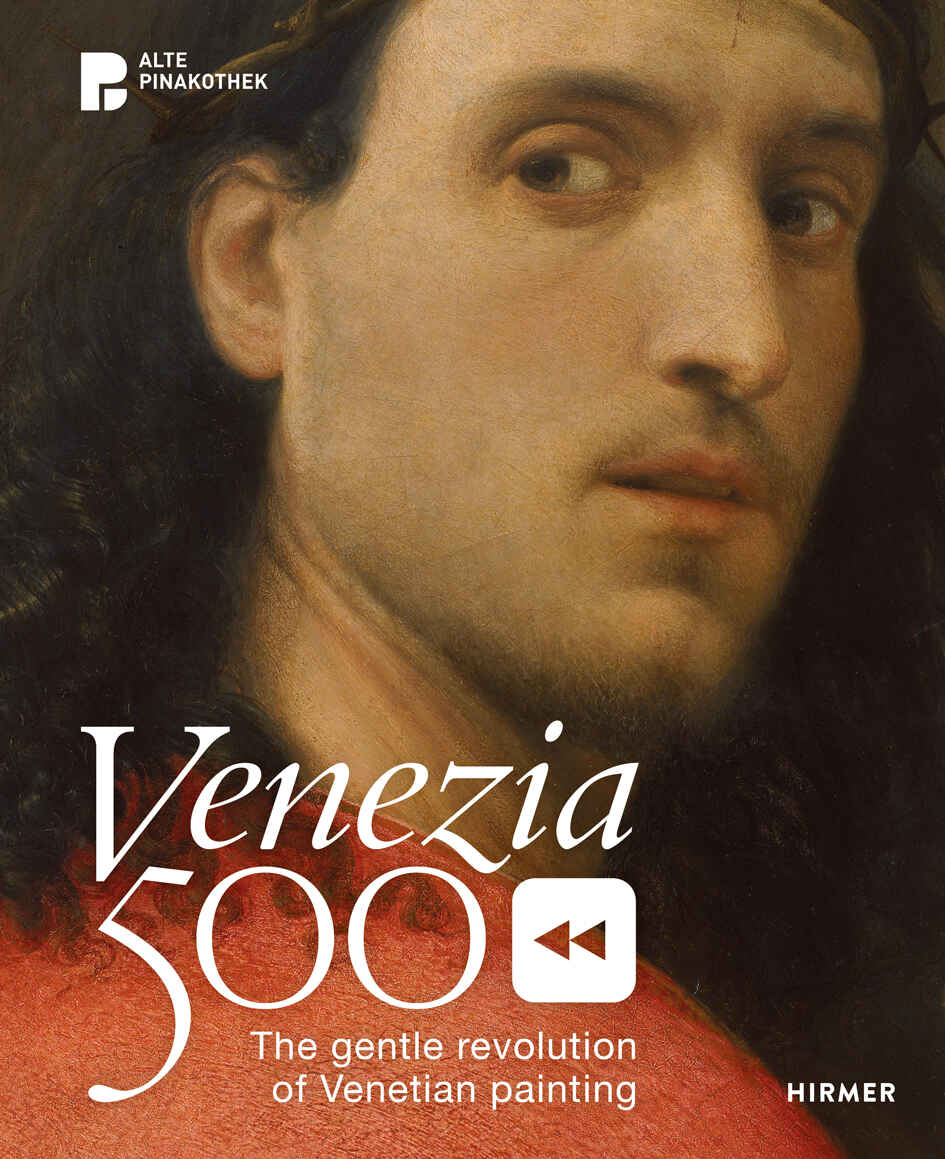

The exhibition at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich and the eponymous catalogue Venezia 500: The gentle revolution of Venetian painting examine masterpieces of Venetian Renaissance art with regard to their innovative power, the context in which they were produced as well as to their contemporary relevance and interpretations.

The English catalogue with nine scholarly essays, edited by Andreas Schumacher: Venezia 500: The gentle revolution of Venetian painting. With contributions by Theresa Gatarski, Johannes Grave, Chriscinda Henry, Henry Kaap, Annette Kranz, Antonio Mazzotta, Johanna Pawis, Andreas Schumacher, Catherine Whistler. Hirmer Publishers, 230 pages with 160 color illustrations, 21.5 x 26.5 cm, softcover with flaps, ISBN: 978-3-7774-4176-4. Accept all cookies to go directly to the English catalogue’s page; we earn a commission: Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

The “gentle revolution” brought to Northern Europe by the Venetian school of painting, represented by masters such as Bellini, Giorgione, Lorenzo Lotto, Palma il Vecchio, Titian, Tintoretto and others, affected in particular landscape and portrait painting.

In his “Foreword”, Professor Bernhard Maaz, General Director of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, reminds us that museum treasures do not explain themselves. Each generation will discuss and interpret them anew in order to decipher their meaning, to demonstrate their contemporary relevance and presentness, and to grasp their significance for the future.

Bernhard Maaz quotes the radical Munich-based post-war painter HP Zimmer who wrote in his diary in 1958: “The Venetians invented painting, and we will reinvent it. […] I want to combine the expressiveness of Pollock and the elegance of Tintoretto. Tintoretto was the Pollock of the 16th century.”

Bernhard Maaz stresses that the Venetians did not invent painting but that early post-war modernism saw and admired their expressiveness, colorism and innovative power. Artists like Zimmer recognized the enormous creative energy and unbridled imagination inherent in this art.

Decades before Zimmer, Max Liebermann wittily remarked: “The works of a Titian or Michelangelo […] are not intellectual but intellect per se.” Bernhard Maaz stresses that the Venetians thematized the autonomy and intrinsic value of color – the brushstroke, the modelling, the nuance. The colour has a life of its own and was not only used to fill in outlines.

The General Director of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen writes that, while the older masters such as Bellini or Giorgione usually only meant much to the experts and connoisseurs, it was Titian and his generation with whom those who followed would engage almost tirelessly.

In the catalogue, nine authors present current research on Venetian Renaissance painting in the first decades of the 16th century. One theme of Venezia 500: The gentle revolution of Venetian painting are the questions about the relationship between humans and nature, and landscape as a place of longing and inspiring retreat.

In his essay, Andreas Schumacher explores how the dream of Arcadia revolutionized landscape and portrait painting. He stresses that all paintings presented in this book are of Venetian origin. Their specific innovative features are due to the specific social and cultural conditions of the lagoon city. And yet none of these works depicts the city of Venice – neither the sacral and profane histories do so, whose real ‘protagonist’ is the landscape, nor the portraits with their window-view backdrops. Instead, the painters invite the viewer to let their gaze wander across the expanse of lush, hilly landscapes, leading it ever deeper and up to the peaks of the southern Alps.

Andreas Schumacher explains that the paintings, drawings and prints presented in this catalogue bear witness to how much the Venetians yearned for green land and open nature; for gardens, a large number of which were also found in the urban area; for the refuge of their villas and country estates; for the areas of agriculture and animal husbandry; as well as for wild nature with its watercourses, forests, rocksand mountains. This longing was emphatically cultivated within the elite circles that dominated innovative artistic activity. The discourse on literary and philosophical questions, the contemplation of pictorial works and the making of music together formed the source of inspiration and, at the same time, the basis of reception for the novel, enigmatic paintings referred to as “poesie”with which Giorgione (1473/74–1510) above all others was to revolutionize the painterly representation of landscape.

Andreas Schumacher stresses that the works of Giovanni Bellini (c. 1435–1516) were an essential prerequisite for the establishment of landscape panoramas as a pictorial theme in their own right – as seen in the large-format drawings by Giulio Campagnola (c. 1482–c. 1516) and his adopted son Domenico Campagnola (c. 1500‒1564), presented in this volume by Catherine Whistler.

Andreas Schumacher underlines that Bellini’s devotional pictures as well as some of his rare secular works, depict man and nature in harmonious union. They leave no doubt that the vast landscapes, which present meticulously studied details of flora and fauna, are not merely decorative backgrounds for the figurative protagonists, but also convey meanings and moods, while having a very deliberate effect on the process of viewing.

In his essay, Johannes Grave shows that the rich, symbolic details in Bellini’s landscapes offered a wide range of material for the Christian allegorical interpretation practised by his contemporaries, but did not necessarily serve a clearly defined goal in the sense of a precisely outlined message. Thus, Bellini’s depictions of a nature created by God and shaped by man encouraged viewers to let their gaze wander through the picture, thanks to the elusive openness of the contexts of meaning. Instead of finding a system of signs that could be clearly deciphered according to the patterns of the early modern language of images, the recipients were encouraged to explore the depictions in an imaginative and associative manner. By intensified viewing and pondering, they thus reached a state of meditative contemplation favourable to devotion.

Andreas Schumacher writes that Giorgione’s work The Tempest marks the beginning of a new chapter in European landscape painting: the painter has freed himself from the traditional task of rendering landscape solely as a space for religious or mythological content and devoted himself to the challenge of developing an artistic expression for creative nature itself in the first place. Giorgione chooses the transitory moment of a thunderstorm to capture on canvas, for the first time, the all-encompassing and unifying effect of the specific atmosphere of a fictitious natural scene. The enigmatic pictorial characters suggest a definite message, which the painter, however, consciously resists just as much as the traditional effort to capture divine creation in detail in a coherent picture. On the contrary, Giorgione demonstratively claims for his art the freedom of poetry, whose reception provided the decisive impetus for the powerful evolution of Venetian landscape painting already initiated by Giovanni Bellini.

Andreas Schumacher stresses that, through the illustrations of ancient and contemporary bucolic texts, Arcadian themes became established in Venetian pictorial art, including the motif of the shepherd in particular (e.g. by Titian), which sometimes had strong homoerotic connotations.

With the lyrical form of male portraits, the Venetians gave European portraiture a pioneering innovation. The genesis, specific expression and reception of Venetian portrait art in all its facets are comprehensively discussed in the present volume by Henry Kaap, Antonio Mazzotta and Annette Kranz.

In his introduction, Andreas Schumacher concludes that viewing the faces of the personalities sensitively characterised by Giorgione and other artistes – who in turn look back firmly at us viewers – enables an almost immediate encounter with the cultural elites of Renaissance Venice, despite a temporal distance of 500 years. The painters and their works revolve around the profoundly human striving for contemplation and beauty, for love and knowledge, and thus around the great longing to live in harmony with creation.

These are just a few details from the catalogue edited by Andreas Schumacher: Venezia 500: The gentle revolution of Venetian painting. With contributions by Theresa Gatarski, Johannes Grave, Chriscinda Henry, Henry Kaap, Annette Kranz, Antonio Mazzotta, Johanna Pawis, Andreas Schumacher, Catherine Whistler. Hirmer Publishers, 230 pages with 160 color illustrations, 21.5 x 26.5 cm, softcover with flaps, ISBN: 978-3-7774-4176-4. Accept all cookies to go directly to the English catalogue’s page (we earn a commission): Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

The exhibition at Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek from October 27, 2023 until February 4, 2024.

Related article: Renaissance in the North.

For a better reading, quotations and partial quotations in this exhibition and catalogue review of Venezia 500: The gentle revolution of Venetian painting have not been put between quotation marks.

Book and exhibition review added on January 1, 2024 at 10:15 German time. Detail about the duration of the exhibition added at 10:37.