Released on June 30, 2023 the colorful Deutsche Grammophon double Audio CD album Sergei Rachmaninoff: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3; Isle of the Dead was recorded by the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin at the Kimmel Center, Verizon Hall in Philadelphia in March 2018 (Symphony No. 2 in E minor, op. 27), and at the Academy of Music on the Kimmel Cultural Campus in January 2020 (Symphony no. 3 in A minor, op. 44) and in January 2022 (Isle of the Dead, op. 29).

Order the double-CD album, the MP3 album or stream the classical music from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

In 1892, Sergei Rachmaninoff aka Rachmaninov graduated from the Moscow Conservatory. As only the third student in its history, he received the “Great Gold Medal” and was immediately able to sign a publishing contract. Both his Prelude in C-sharp minor for piano and his one-act opera Aleko, his graduation composition, performed at the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre, received warm to enthusiastic receptions. However, the premiere of Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony, composed in 1895, conducted by Alexander Glazunov in St. Petersbourg in 1897, was a total disaster. Rachmaninoff himself called it a “fiasco” and claimed afterwards that Glazunov was drunk on the podium. In addition, according to reports of the time, Glazunov made ill-guided cuts to the score and did not rehearse the piece properly.

However, one of the “Mighty Five” Russian composers, Cesar Cui, commented the First Symphony with the harsh words: “If there were a conservatory in Hell, and if one of its talented students were to compose a program symphony based on the story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, and if hewere to compose a symphony like Mr. Rachmaninoff’s, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and would delight the inhabitants of Hell. To us this music leaves an evil impression with its broken rhythms, obscurity and vagueness of form, meaningless repetition of the same short tricks, the nasal sound of the orchestra, the strained crash of the brass, and above all its sickly, perverse harmonization and quasi-melodic outlines, the complete absence of simplicity and naturalness, the complete absence of themes.”

Already before the concert, another of the “Mighty Five”, the composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, had told Sergei Rachmaninoff: “Forgive me, but I do not find this music at all agreeable.”

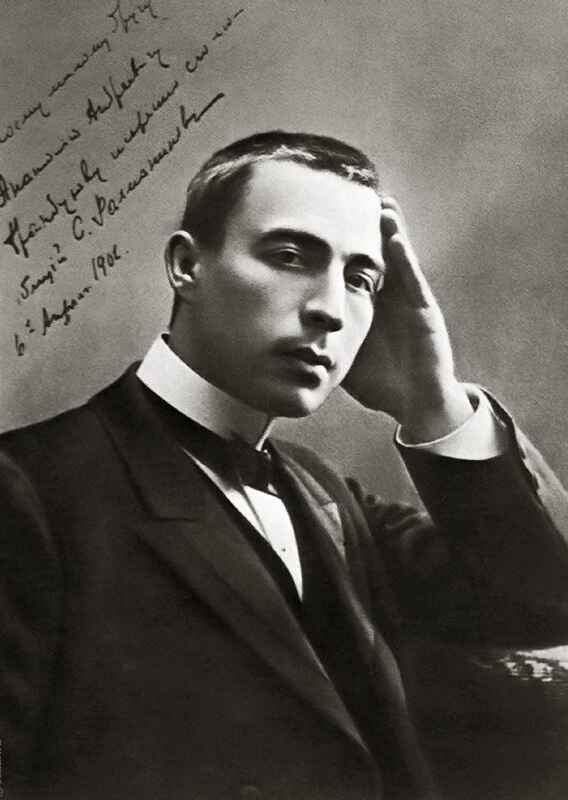

Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1906. Public domain photograph (via Wikipedia) by an unknown photographer. Rachmaninoff sheet music at Amazon USA, Amazon UK, Amazon Deutschland.

Sergei Rachmaninoff did not digest the disastrous first performance reception very well. In the following years, he focused on conducting at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre and on playing the piano, which he did both as a virtuoso soloist as well as the accompanist of the legendary Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin aka Fyodor Shalyapin.

On the advice of relatives, Sergei Rachmaninoff consulted the psychiatrist Dr. Nikolai Dahl, who used hypnosis to treat his patients. The consultations with Dr. Dahl helped the composer regain confidence. Therefore, he dedicated his Second Piano Concerto to Dr. Dahl.

Success as a composer returned with the Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18, for piano and orchestra, composed between June 1900 and April 1901 (recorded by Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra together with the pianist Daniil Trifonov). Despite this well-deserved triumph, Sergei Rachmaninoff only dared to complete his Second Symphony between July 1907 and January 1908, roughly one decade after the distaster of the premiere of his First Symphony.

At the end of 1906, Sergei Rachmaninoff and his family had left Russia for Dresden in order to escape the political and social unrest following the bloody suppression of the so-called, failed “revolution” of 1905. In Germany, he focused on composing. In the CD-booklet, Harald Hodeige quotes Rachmaninoff with the words: “We are living here like real hermits: we see no one, we know no one, and we go nowhere. I am working a great deal and feeling very well.”

Sergei Rachmaninoff composed the Second Symphony between July 1907 and January 1908. The first performance of the Second Symphony took place at the Mariinksy Theatre in Saint Petersburg in early 1908, and was a triumph. Shortly afterwards, Sergei Rachmaninoff himself conducted the piece in Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre. In addition, as soloist, he performed his Second Piano Concerto. The reception was enthusiastic too.

The recording of the Symphony No. 2 in E minor, op. 27 by the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de) is convincing.

The first movement starts with a dark, somber Largo, which introduces the motto theme and quickly offers a glorious abundance of passion. In the booklet, Harald Hodeige writes that this composition adopts the lyrical tone of the late-Romantic Russian symphony to explore the most disparate aspects of melancholy. Indeed, the following Allegro moderato in sonata form continues on this path, offering some stormy moments. The Moderato is intense, not so moderate at all — and a delight.

The second movement, Allegro molto, starts in a lighter mood. Harald Hodeige calls it a translucent scherzo that culminates in a nuanced chorale. Nevertheless, it offers intensity, richness, drama, counterpoints, contrasts between calm and vivacious moments. The rendition by Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra is captivating.

The calm, sensitive third movement, Adagio, is filled with sigh-like motifs (Harald Hodeige), based on two melodies. The fourth and final movement, Allegro vivace, takes up the motifs of the previous ones. It is a joyride through jubilant, colorful, theatrical music.

Luckily, the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin offer a version and an interpretation of the Symphony No. 2 which lasts 61:45 minutes. In the past, far too often, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s masterpiece had been shortened, mutilated by four to seventy-six cuts. In the 1930s and 1940s, some performances in the West had cut off up to 300 bars of music! Find this fine performance at Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Arnold Böcklin: Isle of the Dead (Die Toteninsel), first of five versions, 1880, oil on canvas, 110.9 x 156.4 cm, Kunstmuseum Basel. Public domain (via Wikipedia).

Arnold Böcklin painted five versions of the Isle of the Dead, of which four survive; one in Berlin was destroyed during the Second World War, but the Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin still owns one painting.

The paintings description by Harald Hodeige: in the prow of a small boat stands a figure shrouded in white who can be seen against the background of an island covered in cypresses. The rocky cliffs of the island rise steeply out of the surrounding sea and contain niches that suggest burial chambers. Rachmaninoff’s musical adaptation translates the painting’s contents into three sections of increasing intensity: “Sea”, “Memories” and“Death”.

In the summer of 1907 in Paris, Sergei Rachmaninoff had seen a black-and-white reproduction of one version of Isle of the Dead which, around 1900, was one of the most popular and talked about subjects. In April 1909, while in Dresden, Sergei Rachmaninoff completed his eponymous symphonic poem inspired by the work of the Swiss painter.

Rachmaninoff’s Isle of the Dead begins with a Lento. Dark strings, timpani, harp, horn and woodwinds evoke the waves beating calmly against the base of the cliffs in a gently rocking 5/8 metre. Harald Hodeige notes that, with each stroke of the oars, the music becomes more and more dramatic, as the island seems to draw closer and closer in the listener’s imagination. But, before the dead person can find his or her final resting place, a lyrical middle section begins with an ethereal funeral melody in the higher strings, suggesting a final and impassioned farewell to life. At its climax, however, the music abruptly breaks off and after a series of menacing chords it culminates in a quiet statement of the Dies irae, the sequence from the Catholic Mass for the Dead that refers to the Day of Judgement – a motif that was a regular part of Rachmaninoff’s musical vocabulary. The funeral melody is heard one last time, now in the solo oboe, before the end of the work is once again dominated by the regular beat of the ferryman’s oars as he sets out again on his never-ending circular voyage to bring another dead soul to the island, to its last resting place. After the Lento follow Tranquillo, Largo, Allegro molto, Largo, Tempo I.

Sergei Rachmaninoff not only conducted the premiere of the composition in Moscow in 1909 but, twenty years later, after several revisions of the piece, he conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in a recording at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia for the Victor Talking Machine Company, which was purchased by RCA that same year and became known as RCA Victor.

The 2022 recording (released by Deutsche Grammophon in 2023) by the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin, made at the Academy of Music on the Kimmel Cultural Campus, shows op. 29 in a subtle, yet dramatic light. The 21:52 recording let’s you participate in the final journey, which we all have to make one day. On the double-CD, Isle of the Dead is the last track, but chronologically, it fits in here, directly after the Symphony No. 2.

Incidentally, Sergei Rachmaninoff said, after having seen the original painting in color after having composed his eponymous symphonic poem: “If I had seen the original first, I might not have composed my Isle of the Dead. I like the picture best in black and white.”

Rachmaninoff left Russia for good in 1917, the year of the October Revolution, and spent the rest of his life touring endlessly and giving concerts throughout Europe and the United States. Only six of his forty-five numbered works were written in exile, and these included his Third Symphony, which Rachmaninoff sketched at his villa on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland during the summer months of 1935 and 1936. Nevertheless, its motifs and themes are clearly Russian.

In the booklet, Harald Hodeige writes about the first of the three movement, entitled Lento – Allegro moderato – Più vivo (Allegro) – Allegro molto – Tempo I – Allegro, that the typically Russian melody is entrusted to the veiled sonorities of the clarinets before then being swept away by the full orchestra with a chorale-like passage in which sigh-like motifs and fragments of the Dies irae are heard and which gradually assumes the function of a leitmotif. It is a theme which in the words of the Russian musicologist Boris Asafyev resembles “a song that begins in a way that implies that it comes from afar, from silence and from a state of profound self-absorption”. I noted a forceful, vigorous interpretation by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conveying strong emotions, from start to end.

The second movement, Adagio ma non troppo – Allegro vivace – Alla breve. L’istesso tempo – Adagio, too, begins with this motto, now stated by the first horn to the accompaniment of the harp. For Harald Hodeige, the sumptuously scored and scherzo-like middle section of the second movement recalls the imaginative realm of one of Anatoly Lyadov’s fairytale portraits. For me, the delicatesse and subtlety of the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin was compelling.

The Symphony No. 3 ends with a dancelike finale with a central fugato that combines the opening motto and the Dies irae, revealing the latter’s full range of emotion. The third and last movement, Allegro – Meno mosso – Allegro vivace – Moderato – Tempo I – Andante con moto – Allegretto – Allegro vivace, offers a romantic joyride. You can indulge in the romantic melancholy of a lost Russia, and at the same time witness clairity and modernity in this composition full of imagination.

The Third Symphony received its first performance from the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski in November 1936 and proved a disappointment – not that Rachmaninoff himself was much exercised by this reaction: “Personally I am firmly convinced that this is a good work. But – sometimes composers are mistaken too! Be that as it may, I am holding to my opinion for now!”

Last, but not least, the exiled Sergei Rachmaninoff aka Rachmaninov was fond of the Philadelphia Orchestra’s sound, which he considered prefectly suited to interpret his music, e.g. thanks to its melancholic, dark strings. Under Yannick Nézet-Séguin, the orchestra continues this glorious musical legacy. What a joy to listen too!

The Philadelphia Orchestra under the direcction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin: Sergei Rachmaninoff: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3; Isle of the Dead. Deutsche Grammophon, 2023. Order the double-CD album, the MP3 album or stream the classical music from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Rachmaninoff sheet music at Amazon USA, Amazon UK, Amazon Deutschland.

Related article: review of the Rachmaninov album recorded by Daniil Trifononov, under the direction of conductor Yanick Nézet-Séguin, conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Photograph of Yannick Nézet-Séguin shot by Hans von der Woerd for the 2017 Deutsche Grammophon / Universal Music three Audio CD box of Mendelssohn’s Symphonies 1-5. Order the Mendelssohn box from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.fr, Amazon.de.

Double Audio CD album review of the Second Symphony in E minor, the Third Symphony in A minor and the symphonic poem Isle of the Dead by Rachmaninov / Rachmaninoff added on September 11, 2023 at 12:17 Swiss time.